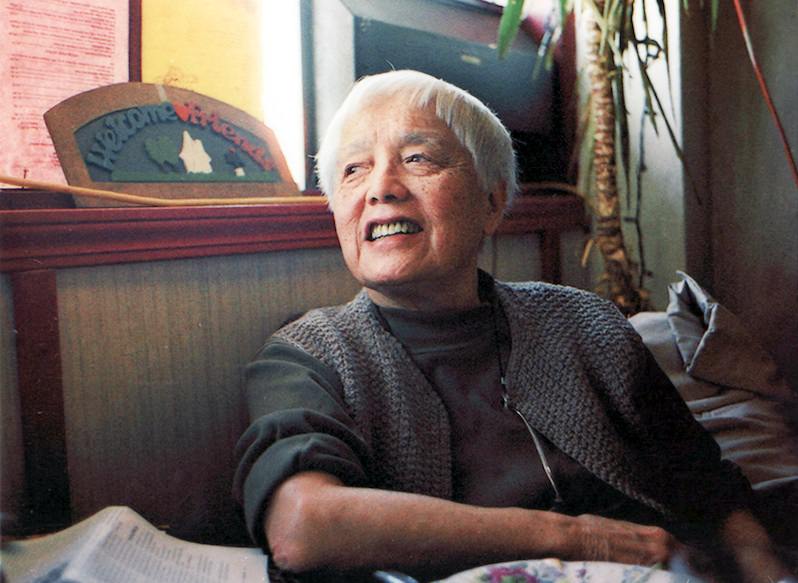

Grace Lee Boggs, American Visionary

At 99 years old, activist and author Grace Lee Boggs reflects on the last century of American history in a Truthdig interview as PBS prepares to air a new documentary about her storied life. "To understand revolution is twofold," she says. "It’s not just changing institutions, it’s changing ourselves."To understand revolution is twofold—it’s not just changing institutions, it’s changing ourselves." americanrevolutionaryfilm.com

americanrevolutionaryfilm.com

“Grace has made more contributions to the black struggle than most black people have.”

— Angela Davis, icon of the black power movement, about Grace Lee Boggs

On Friday, activist and author Grace Lee Boggs turns 99, three days before a new documentary, “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs,” airs nationally on PBS’ “POV” (it can also be watched online during July). Not a conventional biopic, the movie was filmed over many years by Grace Lee (no relation), who met Boggs when she made the 2005 film “The Grace Lee Project” about stereotypes of the women who share that name. The movie tells the story of Boggs’ life — how she got her Ph.D. in 1940, couldn’t find work due to discrimination, moved to Chicago, where she started organizing, and met and married her autoworker husband, James Boggs, and their activism in the black power movement in Detroit. But the movie also explores her unconventional ideas about revolution and how it’s about transforming the self and the world.

Out in San Francisco for a screening of “American Revolutionary” at the Center for Asian American Media Film Festival, Boggs talked about the importance of reflection and conversation, how economic growth has damaged the planet, and the difference between fish and human beings.

Emily Wilson: You say reading Hegel made you think how important conversation and reflection are. Why is that so important?

Grace Lee Boggs: In my autobiography, “Living for Change,” I talk about my experience as a graduate student with a professor whose name was Paul Weiss. Paul was a Jewish philosopher brought up on the Lower East Side of New York. He had a way of speaking so you knew that everything he said had never been said before. It gave me a whole new view of conversation. I think to recognize that conversation is very different from writing, to know how much is spontaneous and how much of it emerges not so much from reflection as much as from reaction to changing realities. Just to deal with the spoken word in a different way than you deal with the written word and to understand how much we know of ourselves and the world through the spoken word, and how it’s essentially a social medium — it’s amazing. It’s given me a lot to think about.

EW: You kept using the word evolution and talking about how we need to transform ourselves for a revolution to take place. What changes do you think need to happen for revolution?

GLB: I think we are an enormously unreflective society, and I think we have thought of revolution so much in terms of changing things and of increasing our economic growth, which has been the Western concentration since the French Revolution. To understand revolution is twofold — it’s not just changing institutions, it’s changing ourselves. Our challenge for this time is to know how much economic growth has damaged not only our planet, but ourselves. In order to achieve that growth, we enslaved a people and exterminated another people. We have to understand how that needs to change and how to change that. That’s the challenge of revolution.

EW: In the documentary, when Coleman Young was elected mayor of Detroit, you talk about him courting corporations because he felt he had to. Is that what you mean by getting stuck in the past? Thinking we need to grow and grow?

GLB: I remember when Coleman Young was elected. He was elected for two reasons — blacks wanted power, and because since the rebellions of ’67, it was very clear that white power could no longer maintain law and order. And to have Coleman, who was a very smart cookie, unable to do anything different — it was a very enlightening experience. It helped us to begin understanding racism and blackness in a different way. Up till then there had been a lot of illusions that black power would be different from white power. To undergo the recognition that it was not different and to meet the challenge of defining what would be different, it was amazing.

EW: At one point in the movie you say you hadn’t thought of yourself as being Chinese or as a woman. When did that change?

GLB: My feminism from early on had been based on the fact my mother did not know how to read and write because she was born in a village where there were no schools for females, and that I was born above my father’s restaurant, and the waiters when I cried said, “Let’s just dispose of her outside — she’s only a girl baby.” That’s one view of feminism, but as I grew and witnessed the world of women, I learned women’s ways of doing and thinking are really very different. There’s a whole concept of the idea of work, and people think about it in terms of jobs, and women do it in terms of caring for the family and home. That’s so different, and they have been beaten down for so long and are just now emerging. EW: There are more women in the Senate now. Do you think having more women in politics changes it?

GLB: There’s a very wonderful book written by a woman Silvia Federici, who teaches at Hofstra College in New York. She has a book, “Caliban the Witch.” I think that the opportunity for a new feminism is emerging, and it’s epochs different from the old feminism. Gloria Steinem and Robin Morgan and the feminists of the ’60s were close, but this is very new, and I think somehow the film is going to help people make that leap. I think we’re going to understand the witch hunts very differently. Starhawk has a wonderful essay about this, “Burning Times.” That philosophic leap is in the offing for us.

My autobiography has just been published in China, and the Chinese editor says it’s going to have quite an impact. It’s very amazing up to now we don’t have any idea what feminism in China is going to mean. All our knowledge of feminism is European and American. We are in a period of spiritual expansion, and there’s a fantastic book, “Translating Feminisms in China,” by two women professors. I think we have had very little understanding of that.

EW: How do you see the youth program Detroit Summer and the community garden focus as part of the movement and what inspired you to start it?

GLB: I’m going to introduce the concept of visionary organizing. I think most people are not conscious of the fact of the difference between human beings and fish. Fish respond the same way to outside stimulus. Human beings respond very differently. Some people are immobilized, paralyzed and other people begin to say, “What can I do?” and what was happening in the ’60s is that young people in the cities were feeling that young people down South were doing marvelous things, and they wanted to know what they could do. Somehow we were able to capture that desire and create a program that met their needs to do something different.

EW: Why that though? Why gardening?

GLB: It all goes back to people who came from the South thought that people born in the cities needed transformation. They had the idea of quick fixes and push-button change without any idea how long it takes things to change, and they thought the vacant lots in the cities had a great use to help young people make a call for transformation.

It was so interesting to see how different people who are raised in the cities and people who were raised in the country respond — I don’t know if you saw the clip of me with Bill Moyers, and he said, “You think a garden can do that?” I don’t think that had ever occurred to him.

EW: In the movie, a young woman asked why you don’t burn out, and you say you’ve been in the same place for more than 60 years. Why does that prevent you from burnout?

GLB: I’ve been in the same house for 50 years. It’s surrounded by vacant, abandoned houses. But it’s been named a historic site by the City Council because so many struggles that have taken place in the city have been strategized there. There’s a book by Vance Packard called “A Nation of Strangers.” He talks about how Americans move, and when you don’t move, you think differently from someone who’s moving all the time. You have a sense of yourself as more meaningful. Coming here on the plane, I watched people looking at movies. And I was thinking what it’s like to be up in the air all the time without any sense of agency of your own. I think the American people need to be more conscious of that concept of agency.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.