‘Freedom of the Press’ Just Words on Paper in Zimbabwe

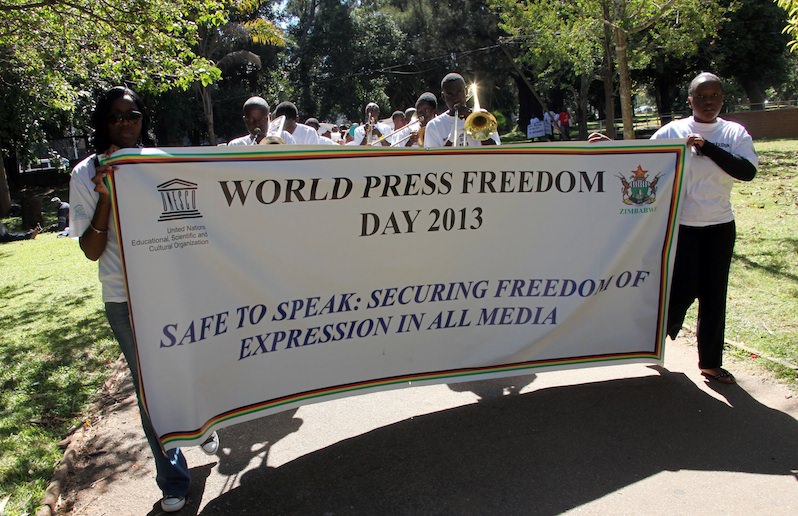

As things stand now, any attempts by the Zimbabwean media to subject public officials to scrutiny and make them accountable for their actions is anathema to the powers that be. Zimbabwean journalists take part in a march to commemorate World Press Freedom Day in Harare on May 3, 2013. The country's journalists called on the government to address media reform issues that would pave the way for a better working environment for them. AP/Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi

Zimbabwean journalists take part in a march to commemorate World Press Freedom Day in Harare on May 3, 2013. The country's journalists called on the government to address media reform issues that would pave the way for a better working environment for them. AP/Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi

Editor’s note: This is the second story in Edna Machirori’s two-part series about the media climate in Zimbabwe. Click here to read the first piece and here for more about the Global Voices: Truthdig Women Reporting project.

In 2013, Zimbabwe was ranked 133 out of 179 on a Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom index. In 2008, when disputed and bloody parliamentary and presidential elections were held, Zimbabwe’s ranking plunged to 151.

The Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe (MMPZ) commented on this period of state brutality sparked by the elections in a book entitled “The Language of Hate” published in 2009.

“Zimbabwe’s national elections in June 2008 witnessed a resurgence in the use of ‘hate speech’ in the government controlled media aimed at publicly discrediting Zanu-PF’s legitimate political opposition in a concerted campaign to portray these groups as traitors and puppets intent on undermining the country’s sovereignty,” the authors wrote.

The book noted that the government-controlled media not only reported offensive and undemocratic sentiments without question but endorsed and amplified them in news and current affairs programs of the state broadcaster and in news and “analysis” columns of newspapers under state and party control.

‘‘Such blatant abuse of these media by Zanu-PF constitutes a grave offense against democratic ideals and humanitarian coexistence in its own right,” the authors argue. “But in Zimbabwe where there are few easily accessible, credible domestic sources of information, the use of these media to propagate the language of hatred and intolerance unchallenged represents a most serious threat to the country’s peace and political stability.”

Zimbabwe’s dismal showings on press freedom rankings are all the more disheartening considering the fact that the nation’s constitution guarantees freedom of speech and of the press.

This dichotomy is symptomatic of a contradiction that is pervasive in many developing countries — the existence of progressive constitutional and policy frameworks on paper that serve only as a smokescreen for repressive clampdowns on the media, human rights abuses and abuses of power. The Voluntary Media Council of Zimbabwe (VMCZ) commented on this in a 2013 study, writing “Despite the fairly generous provisions of the new constitution, Zimbabwe still retains a plethora of restrictive laws. These pieces of legislation were introduced by the Zanu-PF government in the post 2000 era, a period characterized by frenzied law making by an increasingly authoritarian state as a strategy to contain dissent.”

The VMCZ noted that, despite constitutional guarantees, “There are instances when journalists are subjected to forms of violence which range from harassment to arrests and detention.”

Over the last 34 years that it’s been in power, the government of Robert Mugabe has been adept at lulling the people into welcoming dispensations that soon turn into tools of oppression.

The establishment of the Zimbabwe Mass Media Trust soon after independence exemplifies this. Initially the trust, which was supposed to act as a buffer between the media and the caprices of the state, was widely welcomed as a step in the right direction. However, its board of directors was gradually politicized and dominated by Zanu-PF loyalists who promoted a politically partisan agenda.

In a study titled “The State of Journalism Ethics in Zimbabwe,” the VMCZ commented on how Zanu-PF had restructured the state in a way that made it “less tolerant and open to opposition, more militarized, authoritarian and predatory.” It said that by dissolving the media trust, the state removed the buffer, “resulting in the department of information and publicity in the President’s Office assuming direct control of editorial processes and decisions at both Zimpapers and Ziana.”

This politicization applies to boards set up to oversee the operations of state-controlled media entities such as the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, Zimbabwe Newspapers (Zimpapers) and the Zimbabwe Inter Africa News Agency (Ziana). Over the years, this has given ministers of information carte blanche to dismiss editors deemed not to be toeing the party and government line.

Early casualties included the late Willie Musarurwa, who was fired as editor of The Sunday Mail, and Geoffrey Nyarota, who was relieved of the editorship of The Chronicle, both titles in the Zimbabwe Newspapers stable. Nyarota was hounded out after his paper had published an exposé on a scandal that came to be known as “Willowgate.”

The scandal involved a racket in which government ministers and other officials abused a vehicle acquisition scheme to obtain cars from the Willowvale government auto assembly plant at subsidized prices to sell at exorbitant prices for personal gain.

In a case of shooting the messenger, Nyarota’s brand of investigative journalism was denounced as a threat to a nascent democracy. This was an ironic reaction in view of the fact that official corruption is now rampant and a culture of impunity is firmly entrenched.

Nyarota fled to the United States in 2002 before the banning of the Daily News, an independent newspaper of which he was editor-in-chief. He returned to Zimbabwe only a few years ago.

In an ironic development, he was appointed at the end of last year to head an information and media panel tasked with inquiring into the state of the media in the country.

The panel was set up by the same information minister widely perceived as the architect of Zimbabwe’s draconian media laws. Observers question how the panel can make any difference as long as the repressive media laws are still in place.

These laws were supposed to be abolished during the life of a government of national unity formed at the recommendation of the African Union after disputed elections in 2008 that Zanu-PF was accused of rigging and using violence to terrorize the electorate. Zanu-PF blocked the implementation of media and electoral reforms until last year when it won another disputed election. As things stand now, any attempts by the media to subject public officials to scrutiny and make them accountable for their actions is anathema to the powers that be.

These tendencies could have been nipped in the bud if the press had been allowed to play its role as a watchdog for the public interest during the early years. Instead, journalists in some sections of the media have been turned into lapdogs.

But just how far the Mugabe administration was prepared to go to muzzle the press and crush dissent became alarmingly clear in 2000. That year was marked by two events that sent Zanu-PF into panic mode.

The first was the Mugabe government’s defeat in a constitutional referendum in which a “yes” vote would have sanctioned the establishment of a one-party state and a life presidency.

The government was also shaken by a strong showing on the part of a new opposition political party, the Movement for Democratic Change, which won 57 out of 120 contested parliamentary seats only two years after its formation.

Fearing he was losing his grip on power, Mugabe, who is now 90, appointed what he termed a “war cabinet” tasked with fighting perceived enemies of the state at home and internationally.

This military-style cabinet included a propaganda minister, Jonathan Moyo, a former political science lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe.

Moyo’s first tenure as chief government propagandist from 2000 to 2005 marked the darkest hour for the journalism profession and for all those who cherished freedom of the press. One of his first actions was to undertake a purging of experienced editors and journalists. Hundreds lost their jobs and scores went into self-imposed exile in Britain, the United States and other Western countries.

The propaganda minister replaced experienced editors with youthful and pliant novices who could be manipulated to amplify their master’s voice. A study conducted by the VMCZ, which campaigns for media self-regulation, shows that these authoritarian interventions have resulted in a drastic decline in journalistic standards and ethics as well as the entrenchment of propaganda journalism.

“Some of the journalists interviewed [for the study] attributed the decline in professional ethics to the absence of moral and thought leadership both nationally and within the profession itself,” the VMCZ noted. Contributing factors include the flight of experienced journalists into the global diaspora and the removal of experienced editors from the official media, which has resulted in a generational disconnect.

The VMCZ pointed out that state control and interference had resulted in the creation of a media environment characterized by “a genuflecting and ‘patriotic’ state media on the one hand and a vociferously ‘oppositional’ private press fighting on the side of the political opposition.”

Powerful individuals can, with impunity, harass, abuse, threaten and order the arrest of nosy journalists, and the police force — which is also politically compromised — will gladly comply. This exerts enormous pressure on reporters, leading to self-censorship.

The siege mentality within the government in 2000 led to the promulgation of draconian laws that virtually criminalized journalism and the media. Under these measures, journalists have been harassed, intimidated, detained, assaulted, abducted and arrested. These harsh and archaic laws remain in force today.

Some of the decrees journalists must tiptoe around include the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act, the Public Order and Security Act, Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act, Broadcasting Services Act, Censorship and Entertainment Act, Interception of Communications Act and Official Secrets Act.

Under the access act, journalists must be accredited by the government’s Media and Information Commission, and media organizations must be licensed by the same body. Noncompliance can bring hefty fines. The measure has been invoked to ban newspapers and to bar international newsgathering organizations and broadcasters such as the BBC and CNN from reporting from Zimbabwe. Their correspondents and those of overseas newspapers cover events from bureaus in South Africa.

The government has used the Broadcasting Services Act, which provides for the opening up of the airwaves to private players, to maintain the monopoly of the state broadcaster, which does not even pretend to be anything other than a Zanu-PF mouthpiece. Only two radio broadcasting licenses have been issued, both to ruling party loyalists.

Stations that provide an alternative source of information for Zimbabweans include the Voice of America’s Studio 7, U.K.-based SW Radio Africa and Voice of the People. All manned by exiled Zimbabweans, these stations beam broadcasts into Zimbabwe. The government regards them as pirate stations and regularly subjects them to Soviet-style jamming.

In practice, a journalist can be arrested under any law. Repeated calls for media reforms have been ignored.

The press is subjected to varying degrees of control all the time but clampdowns escalate in the buildup to national elections and their aftermath.

This was the case when Zimbabwe held disputed national elections in 2013. A reporter based in Chinhoyi, a small town north of the capital of Harare, was abducted by masked men, brutally assaulted and left for dead. He was lucky to be found and taken to a hospital where he eventually recovered.

Two female journalists were detained at the headquarters of Zanu-PF and interrogated by security agents. They were released only when the then-information minister intervened. Numerous other cases have been reported.

Other abuses perpetrated with impunity, particularly by supporters of the ruling party, include the destruction of publications that are critical of the government and barring the distribution of such newspapers, particularly in rural areas.

Given this backdrop of media repression, it is clear that the ruling regime has no intention of delivering on the promises of press freedom written into Zimbabwe’s constitution.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.