Fighting for Peace on ‘Hurricane Street’

This impassioned, timely memoir about the American Veterans Movement picks up where author Ron Kovic's "Born on the Fourth of July" left off. The cover of the longtime peace activist's new book. (Akashic Books)

The cover of the longtime peace activist's new book. (Akashic Books)

The cover of the longtime peace activist’s new book. (Akashic Books)

The following excerpt is from Ron Kovic’s new book, “Hurricane Street.” Published by Akashic Books—which also has published the 40th-anniversary edition of Kovic’s first book, “Born on the Fourth of July“—”Hurricane Street” was released July 4. It recounts the spring of 1974, when Kovic led a two-week hunger strike at the Los Angeles office of U.S. Sen. Alan Cranston. The title refers to the location of a small house Kovic rented in the oceanside town of Marina del Rey, Calif., where he worked on his first book and came up with the idea for the American Veterans Movement. From 4 to 7 p.m. PDT on Sunday, Kovic will have a conversation with Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer at the Robert Berman Gallery at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica, Calif., to celebrate the publication of “Hurricane Street” and the 40th anniversary of “Born on the Fourth of July.” The program will be followed by a Q&A and book-signing. You can RSVP here.

The March

July 4, 1974

The day of the big march has finally come and it’s clear from the very start that we are not going to get the numbers of veterans showing up that we hoped for. The air is hot and sticky, a typical summer day in the nation’s capital. By eleven thirty, fewer than a hundred veterans and our supporters have arrived at Meridian Hill Park, and by noon our numbers have swollen to a measly one hundred and fifty.

Bobby and his little brother Charlie unfurl the thirty-foot AVM banner while Joe, Eddie, and Sharon hand out AVM membership cards and buttons to everyone. There are several American flags that were donated by one of the local VFW chapters and half a dozen red, white, and blue AVM flags on poles that we brought with us from LA. Some guy from Virginia in a Marine Corps dress blue uniform with a bugle keeps blowing “Taps” until we ask him to stop. A few local reporters show up and are milling about the crowd, doing interviews and asking questions as it becomes more and more clear that the Second American Bonus March is going to be a big bust.

I try to put on a brave face as one of the reporters walks up to me, asking where the tens of thousands of veterans I promised are. I don’t know what to say other than realizing in this moment that the reality of the situation has finally caught up with me and there’s no longer room for excuses. I can see by the looks of some of the others around me that they are becoming concerned. Joe Hayward is already joking about how the march is a farce and how this will be the end of the AVM.

I do my best to keep everyone’s spirits up and sometime around two p.m. we begin to move down 16th Street. It’s all getting a bit absurd as we shout and chant and try to look dignified. Marty and Nick are being pushed by some of the other veterans and I do my best to maintain my composure. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry and I feel ashamed and embarrassed as our sorry procession slowly rolls down 16th Street. I can’t wait for the march to end.

The great crowds we hoped for are nowhere in sight. A few people on the sidewalk wave at us and I distinctly remember one old man getting up from his lawn chair and saluting. But for the most part people seem a bit puzzled by our ragtag procession as we head into Lafayette Park to set up our tents.

I am still hoping inside that the image of disabled Vietnam veterans camping out in front of the White House will inspire others to join us, but as we settle in, our dwindling numbers say it all. Fewer than fifty of the original marchers remain. Many say they are tired and want to go home, while others openly admit they are fed up because the march hasn’t turned out the way they hoped it would.

Later that day, my mother and father drop by our campsite—just as they promised—having driven all the way from Massapequa and parked their motor home a few blocks from the White House.

“Happy birthday, Ronnie!” my mother shouts, giving me a great big hug and handing me a present. “You can open it later.”

“We’re really proud of you, Ronnie. Happy birthday,” my father says softly, leaning over and placing his hand gently on my shoulder.

I am so happy to see them, and realize just how much I have missed them. They’ve always been there for me and have never let me down: praying for me at a special novena Mass at our church in Massapequa while I fought for my life on the intensive care ward in Da Nang; visiting me at the St. Albans Naval Hospital with other wounded marines; patiently caring for me when I was at the Bronx VA. They stood by me when I was arrested for protesting the war, and when I shouted down President Nixon with two other disabled veterans during his acceptance speech at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami. Even when our neighbors back in Massapequa rejected me, telling their children to stay away from me, afraid I might influence them with my “radical ideas”; and after the many nights I came home drunk from Arthur’s Bar, tormented by the war, crying out and bitterly cursing God and my country, blaming God, blaming everyone.My mother and father have never walked away, never abandoned me. They stood by me, continuing to love me despite my anger, suffering, and rage. They saw me through my sorrows, holding me in those dark moments when I felt so alone and wondered if anyone could ever understand, as I cried and shared with them the terrible things I had seen and done in the war. They had been and would always be there for me, and that gives me great comfort at a time when I feel so dejected about the failed march.

That evening I take them around our campsite, introducing them to all the guys, and even giving my mom an AVM button which she places proudly on her blouse. I try my best to act as if nothing’s wrong, but a part of me wants to tell them how frustrated and embarrassed I feel. What am I doing here with all these crazy people? I think to myself. I want to get out of here. I want to go with you and Dad back to Massapequa and leave all this madness behind, I imagine saying to my mom. I need some peace and quiet away from all of this.

But I keep those thoughts to myself and feel sad as I watch my mother and father leave that evening, still wishing I could go with them. The Second American Bonus March has been an unmitigated disaster.

***

Not long after my parents leave, I open the birthday present my mother gave me. It is a biography of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and my mother, in her perfect Catholic school cursive, has written an inscription inside: Dearest Ronnie, I give you this book on your twenty-eighth birthday, July the Fourth 1974, with love in hopes that it will inspire you.

I hold the book in my hands and can’t help but think back to when my mother brought me another book, Sunrise at Campobello, a play by Dore Schary, while I was recovering at the St. Albans Naval Hospital in New York in 1968; it told of Franklin Roosevelt’s great struggle with polio and ended with his inspiring speech at the Democratic Convention in 1924.

As night comes over our makeshift campsite, I transfer out of my wheelchair and onto my rubber mattress, and sometime around nine p.m. we all watch the great fireworks display above the Mall—rockets bursting in air, strings of firecrackers exploding, Roman candles popping, children with their sparklers turning night into day, reminding me of so many other Fourth of Julys when I was a boy growing up in Massapequa. Hundreds of thousands of people have traveled to Washington today to celebrate America’s 198th birthday, but few if any know we are here.

After coming home from the war, the Fourth of July has always been a frightening day for me. It is no longer the celebration it once was. The terrible sounds and fury of the night’s fireworks display now remind me of Vietnam—bullets cracking all around me, men being shot, men dying, my own wounding, the exploding sound next to my ear of the bullet that was to paralyze me for life. Independence Day has now become for me a night to simply endure, to take cover, to get into the house, shut all the windows and doors, turn up the TV really loud, place my fingers in my ears, and try to survive.

I snap back to the present as the explosions become less frequent, until finally it is quiet and another Fourth of July has ended.

As the days pass, fewer and fewer members of the media show up and we continue to lose hope. We are tired and dirty—none of us have showered. Tourists drop by and we explain to them why we are protesting, but my heart just isn’t in it anymore. And I am not the only one. Arguments soon begin to break out as things become increasingly chaotic.

At one of our nightly meetings, a very frustrated Bobby Mays insists that we have to consider a change in tactics, and to my surprise, everyone agrees when he suggests we take over the Washington Monument. Tony D. quickly follows, proposing that we do a double takeover, or “two-pronged assault” as he is now calling it, where we will take over the Washington Monument and the White House at the same time. It will be a coordinated, nonviolent seizure of both national symbols by the AVM, with the demand to meet with the president to discuss the national veterans crisis. It is a bold move but what else is there to do? With the march now in a shambles we have to do something. And if we are ever going to reclaim our dignity and self-respect, this will be our last chance.

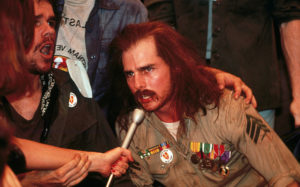

Ron Kovic was a guest on “Live at Truthdig” on June 30.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.