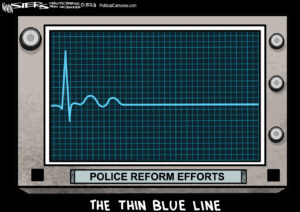

Ferguson: Baffling Decisions Continue to Provoke a Traumatized Community

There is no question that the Michael Brown case has been mishandled from the very beginning. With the news conference Monday by St. Louis County prosecuting attorney Robert McCulloch, we now know that it was mishandled to the very end. AP/David Goldman

AP/David Goldman

AP/David Goldman

There is no question that the Michael Brown case has been mishandled from the very beginning. With the news conference Monday by St. Louis County prosecuting attorney Robert McCulloch, we now know that it was mishandled to the very end. His defiant, triumphalist, sarcastic tone served only to inflame a community that was already skeptical about his commitment to deliver justice in the Brown killing. Without changing any of the facts, the entire situation could have been handled in a way that would have at least ameliorated the public outcry, confusion and anger. At best, Brown would still be alive. The prosecutor could have couched his statement in regret and remorse, recognizing that another outcome could have easily transpired. Police officer Darren Wilson, who shot and killed Brown, should have maintained his posture of surveillance rather than pursuit. Had he done so, Brown would more likely have been apprehended than killed.

Wilson mishandled the stop of Brown and friend Dorian Johnson. He made two critical mistakes that led to the killing of Brown. He testified that his intent was to keep the suspects in view until other officers could arrive. It is now confirmed that just 90 seconds elapsed between the time Wilson called for backup to the time he reported that Brown was dead. Ninety seconds is all that separated a normal arrest from a horribly tragic killing of a young unarmed black teenager. If Wilson had had sufficient experience, maturity or training, Brown would still be alive and Ferguson, Mo., would be at peace. But instead, by placing his vehicle in such a way that Brown could pin him inside, Wilson put himself at a tactical disadvantage that caused him to compensate with deadly force. That was the first mistake.

Wilson encountered two young black men walking down a sleepy street in Ferguson. He pulled up alongside the two and instructed them to walk on the sidewalk instead of the street. The first young man politely responded, “We’re almost to our destination.” That could have been the end of it. But for some unknown reason, Wilson persisted as the second young man passed his driver-side window. The officer said to him, “Why don’t you guys walk on the sidewalk?” This young man was not as polite. The officer then called for backup, reporting that he had “two on Canfield” who were blocking traffic. He then backed his patrol vehicle into a position blocking the path of the two and confronted Brown. From there, Brown pinned the officer in his car, beat him about the face and, when Wilson pulled his weapon (another mistake?), he was able to redirect Wilson’s aim and cause the bullets to be discharged into the door. Then he ran away.

After Brown ran away from the vehicle, Wilson could have regained tactical advantage by following him in his cruiser rather than on foot. That was his second mistake. If he truly feared Brown’s power (as he testified regarding the scuffle inside the vehicle), then it makes no sense that he would put himself in further jeopardy by chasing Brown on foot when he knew help was seconds away.

Witnesses testified that Wilson shot at Brown while the teenager was running away. Wilson admits several of his shots at Brown missed. Because Wilson was such a bad shot, there is no physical evidence to refute or substantiate these witnesses’ accounts. It is still credible that Wilson shot at Brown while he was not a threat and running away from the officer.

At a point Brown did stop and turn around. Both of these actions could be characterized as in compliance with the officer’s commands or as the logical realization that running away would not stop a bullet. Witnesses testified that Brown raised his arms in surrender while the officer was still shooting at him.

Wilson testified, as did other witnesses, that after turning around, Brown charged at Wilson and the officer shot him several times. Other witnesses say that after turning around, Brown was falling toward Wilson after being shot and Wilson continued to shoot while Brown was injured and crumpling to the ground.

Wilson testified that he shot Brown in the head. Curiously, he also testified that he saw his demonic facial expression melt away into a blank stare. It seems odd that Wilson would both watch the fatal shot strike Brown in the top of his head and be able to see his facial expression so carefully.Wilson, in all likelihood, would not have predicted the national scope of his actions that August night. McCulloch certainly should know better.

Without changing any of the facts that the prosecutor reported during his news conference, he could have framed the grand jury’s decision in a way that would bring healing to what he knew was a tense situation. Instead, he acted with antagonism toward both the victim and the thousands protesting in his name. The first mistake was to schedule the news conference at night. Many commentators and legal analysts questioned the wisdom of that timing. It favored anyone who wanted to riot, loot and burn, and put at danger those who wanted to exercise their rights to free speech and assembly. Some even speculated that the schedule was calculated to provide such an opportunity for mayhem.

Alternatively, the prosecutor could have convened the news conference for 8:00 a.m. He could have outlined the series of events as tragic, unfortunate, unnecessary and yet legal. That would have given both sides of the issue some of what they needed to feel that the justice they sought was truly considered.

The prosecutor could have given a variety of legal scenarios describing how Wilson could have engaged Brown. Wilson had the legal right to pursue Brown but had no legal requirement to do so on foot. He had every right to wait for backup after losing his fight with the teenager. The prosecutor could have highlighted the timeline of 90 seconds, emphasizing that there would have been no negligence attributed to Wilson if he had continued to observe Brown as he ran away while other officers arrived on the scene. The prosecutor could have acknowledged that Wilson had never fired his weapon in the line of duty. And he could have reluctantly (rather than gleefully) acknowledged that though Wilson did not perform in an exemplary fashion, he performed in a legal fashion.

However, this does not satisfy those who want justice for Brown. We still have unanswered questions. Facts are still not clear regarding what happened that day. My first reaction to the testimony of Wilson is that it is not possible to reconcile his account of the shooting sequence, his decision making process, and his scenario of the actions and reactions of Brown with the audio recording of the 10 shots and a total elapsed time of 90 seconds. It is simply impossible for Wilson to have observed the actions of Brown and made the considered judgments he claims to have made all in that brief minute.

Wilson’s testimony reeks of careful construction to fit his testimony into the law, the available evidence and requisite fear that would avoid a conviction. The most amazing part of the testimony is when Wilson claimed he felt like a “5-year-old holding on to Hulk Hogan” when he struggled with Brown at the car. Brown was 6’4″, an obese 292 pounds and 18 years old. Wilson is 6’4″, 210 pounds and a conditioned, trained police officer. His characterization of his state of mind is incredible (in the very technical sense of that word).

But the hard truth that those who want justice for Brown have to accept is that the grand jury did not have nine jurors who could agree that a crime had been committed. Their agreement was hindered, not helped, by the lack of a recommended charge from the prosecutor. Their agreement was hindered, not helped, by the tsunami of evidence provided by the prosecutor (some say intentionally to overwhelm) rather than a clear evidentiary path to a charge, as is usually the role of the prosecutor. Given all of this, it remains that Wilson had several legal options before him that day. For reasons we can only speculate, Wilson chose the deadly option. Given the law, given the actions of Brown, given the conflicting witnesses, given the physical evidence, a grand jury could not find Wilson guilty. However that is not the job of a grand jury; that is the job of a trial jury. And a trial jury should have had an opportunity to sort out the credibility of the conflicting witnesses, the clashing interpretations of the physical evidence and the motives of Wilson, who, at each opportunity, chose the deadly option.

Show your support for Truthdig’s independent journalism and donate today.

Rev. Shockley: Support Bringing Truth to a Post-Truth Era from Truthdig on Vimeo.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.