Exile’s Eye

To understand the pain of deracination, Raoul Peck resurrects the legacy of apartheid-era photographer Ernest Cole. A self-portrait of Ernest Cole's as seen in "Ernest Cole: Lost and Found." (Magnolia Pictures)

A self-portrait of Ernest Cole's as seen in "Ernest Cole: Lost and Found." (Magnolia Pictures)

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is playing in theatres around the country.

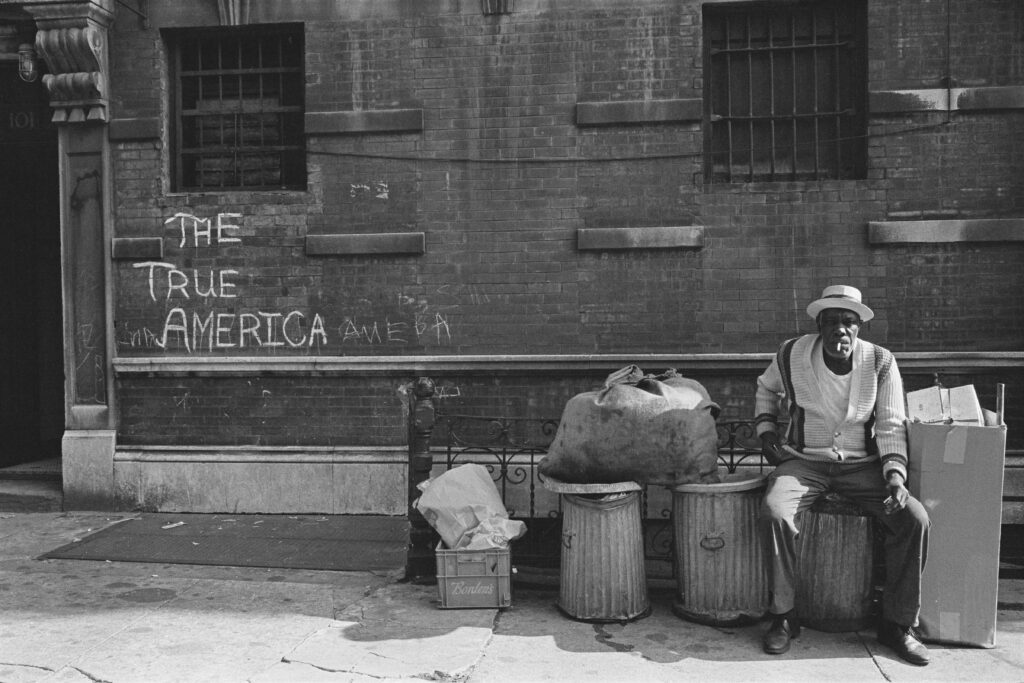

Former Haitian minister of culture, filmmaker and Oscar nominee Raoul Peck is in the business of exhuming cultural greats. He has dug deep to resurrect Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba and civil rights activist and writer James Baldwin. Now, with “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found,” he tells the story of one of the first photographers to document everyday life in apartheid-era South Africa.

In 1966, Cole emigrated to the U.S. looking for a free world in which to live and work. Faced with abuse and racism, he struggled in exile and often disappeared from public life before finally passing away in 1990. It is a pain that Peck, who was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, knows all too well. At 8, his family fled Haiti for the Congo. He later studied in Germany and France before returning to his native country. He sat down with Truthdig shortly before his film’s U.S. release. Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Truthdig: How did you come to know about Ernest Cole?

Raoul Peck: In the ’70s, I came to Berlin as a young man to study. I was 17. Berlin, at the time, was a very political city; both East and West Berlin. A lot of the movements were based there, there were a lot of people in exile who felt welcomed. There were refugee programs. I grew up there, these people were my elders. We’d use Ernest Cole’s pictures for demonstration, for pamphlets, etc. Even though we didn’t know the name [of the photographer]. For the first time, we had actual images of what was going on in South Africa, because there was censorship within the country. It wasn’t until later, when I saw the book, “House of Bondage,” that I knew it was Ernest Cole.

TD: And what made you want to make a film on him?

RP: It was a slow process. When the family reached out to me and asked me if I would be willing to consider making a film on Ernest Cole, I was still working on “Exterminate All the Brutes,” and it was a very heavy film to make. But I told them I would think about it, but I would definitely help them recover the archive, and then to classify it. So I found some money for them to do that. And then two years into it, I finally saw what that material meant and I thought how I can make a film that resonates today. Because I only make films from a political point of view in a way that they can resonate about what we are confronting today. That’s a sine qua non for me. I don’t make films about the past. I use the past to make clear what’s going on today, to help people understand what’s going on today. So all those layers were in the story for me. It is, of course, an incredible, powerful story, and Ernest Cole is an incredible character, and also that he stands for many others who were in exile and died in exile.

TD: What makes you want to make a film in the first place?

RP: I came into filmmaking through politics. I grew up in a time where you asked yourself, what do you do for your country? Our countries were still either colonized or under dictatorships. And for me, the answer was clear: I’m going back to Haiti to fight. In the U.S., people were starting to protest against the Vietnam War, and in the East, there was resistance as well. So filmmaking was not only a privilege, but also an instrument to fight to express myself, and not express myself in a personal way. I didn’t want to be a poet. It was about, how can I be of some use? My cinema could not be a propaganda machine. My elders were making militant films and I knew that wasn’t going to work. You cannot preach to people who are already convinced. For me, it was going to be the general audience, the general public, and I had to start a conversation and bring in arguments and images, bring in stories that can open up the field and not just tribalize everything in their own little ideas and minds.

TD: You have talked about how you go away from America, from its systems of racism to create work. That theme is reflected in Ernest Cole’s life too. He keeps saying he is homesick. Is that something that resonated with you?

RP: Yes, of course. And not only that, I was able to understand him very clearly in a sense that, how did he live through those years? Because all the documents I read at the time when I started working on it, they were like, well, he was famous everywhere in the world, and then he stopped photographing and became crazy or homeless. As if there is some sort of pathological issue. There was no context about the time he was living in, no context about what was his struggle to get his work seen and to get assignments that didn’t have to do with his skin color.

TD: Did you relate to his life in exile?

RP: I know, even today, what exile can do to you. Most people don’t. That’s why the whole debate about immigrants or illegal immigrants is totally ignorant. People don’t leave their homes on a whim or even believing it will be better elsewhere. No, you’re leaving hell. Ernest Cole was leaving behind a prison, where everything was censored, where he was not recognized as a human being. How long can you live in those conditions? He found what was sold to him as a free world. And he realized, it was not at all free, at least not for people like him. I understood the frustration. I understood that pigeon hole: well, you’re Black, so you should stick to the Black themes.

TD: What do you think saved you from meeting Cole’s fate?

RP: Thank God there were people like James Baldwin to teach me that you have to create your world. You have to create your own assignment, your own destiny, and that nobody can tell you what to do or assign you any place or whatever it is. And coming from Haiti, we knew we had to liberate ourselves. I was able to understand how Ernest Cole could lose it after years of not being able to do anything in his country. His work is basically unknown in South Africa.

TD: The book is no longer banned, correct?

RP: No, it was re-edited last year and there were a few major events around the book. It was sold worldwide and now it’s everywhere again. It’s the start of something new.

The film will be a major element in its revival, the same way “I Am Not Your Negro” pushed re-editions of James Baldwin around the world. You could not find too many of [Baldwin’s] books, even here in New York; Maybe you could find one or two books, but that’s it. Now everything is out again and I think that’s what will happen with Ernest Cole as well.

TD: You worked with Cole’s nephew, and we know the family found it hard to get his photographs back from agencies and publications. Was the making of the film difficult for them?

RP: They have tried for the last 10 years to have a film made on Ernest Cole and now they are on a much more powerful footing. First of all, they have all the material. There will be a lot of exhibitions. There was one in MoMA that ended a few months ago. There is a new book about the U.S. photos. And a whole new generation of creators will have the possibility to work with his photos. We are on the verge of something new. And with all those pictures that are still unseen — Magnum has only selected 3,000 pictures so far — there is so much work to be done, and that’s exciting. It’s the beginning of an extraordinary adventure. The Hasselblad Foundation knew of the film and they didn’t want to be in an awkward position, so they had a press release a day before the opening in Cannes, saying that they will be giving back Cole’s pictures to the family.

TD: I found the voiceover fascinating. In the credits, you and Cole are listed as writers. How did you write it?

RP: It’s an organic process. I decided that Ernest Cole needed to tell his own story. Then I was like, where are his texts? Where are his diaries, where are his letters? I studied all of this in detail. The text in “House of Bondage” is extraordinary. Very precise, poetic. It’s a great political analysis. You could understand his critique of South Africa, his criticism of apartheid, how he explained what actually apartheid looks like in your daily life, and his humor. So once I had all this, I built the character. My team did wide research to find everybody that crossed his life. We already had the factual elements.

“I decided that Ernest Cole needed to tell his own story.”

The last years of his life, he was in contact with a woman he met at Magnum years ago, and they started talking almost every day while he was in the hospital. He told her about his suicidal thoughts, about his anger, all those things. So I took that and just put it in his words.

We tracked two Swedish women he knew. They are 85-86. So the writing bit is easy, as long as you have the discipline to rely only on facts. We found a group of four young Black photographers who actually saw him in Penn Station and went up to him and said, ‘Oh my God, it’s the great Ernest Cole.’ They told us their conversation. That he was not talking much, he was well dressed, but just sitting in the station. I wrote every aspect of the voiceover based on the exact fact.

TD: Why did you pick LaKeith Stanfield?

RP: Toward the end, I knew I needed an Ernest Cole. I needed somebody that would not be just a voice, I needed an actor. I needed someone to feel it in the same way as I understood and felt in my own skin, what Ernest Cole was going through. I love LaKeith’s voice; for me it was perfect, even though it has nothing to do with the real Ernest Cole’s voice. Coincidentally, he had just started photography himself. Four years ago, he bought a Leica.

TD: The film includes clips from a documentary with Ernest Cole in it where he says he believes that South Africa will one day be free. What is that documentary?

RP: It’s a documentary from Jürgen Schadeberg. He knew Ernest when he was very young. He was one of the editors at Drum magazine. So he is a kind of white chronicler of Black artistry. He followed musicians, painters, photographers. He has an enormous archive on the Black cultural scene in South Africa. It’s the only known film interview of Ernest Cole. I use it in three or four different places, as a reminder, and as a narrative tool. But other than that, there were some photos of him by other photographers, and some of him by him. He gave the camera to somebody to take the picture. The film is also an homage to all the others who spent time in exile — musicians, writers, artists. It was important that beyond Ernest Cole, the film was also a portrait of a whole generation.

TD: And some of them died so young. Cole’s roommate was a South African sculptor who had a heart attack while he was in a record store …

RP: That’s the price that they paid for exile, for repression in their own country. That’s a price a lot of exiled people and refugees pay when you have to bring your whole family into another country. It’s already an incredible difficulty. Then when you encounter racism and abuse, it only makes it harder. And at the time, it was difficult. There were not that many South Africans in the U.S. Because to leave South Africa, you needed special authorization. You needed visas. Unless you had powerful people helping you, there was no way you could get out.

TD: Coming back to the present, what do you want the audience to take away from the film? Apart from your very clear message about racism and immigration in the country.

RP: I also want the audience to see him as just a human being, as a young artist trying to be a part of this world, no matter what his color is, no matter where he comes from. I hope every person will bring their own story into Ernest’s story and recognize themselves. And recognize the absurdity of racism, that absurdity of looking at the other as an animal or as something irrelevant when you know you are always the other of somebody else in this world. So, I hope it will teach some people humility.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.