Education in Solidarity

The Trump administration has unwittingly created the grounds for a powerful alliance among scientists and humanists, medieval literature students and assembly line workers. Palestinian children take an English lesson in a makeshift classroom in a school compound in Gaza City, which is also serving as a shelter for displaced people. (AP Photo/(AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

Palestinian children take an English lesson in a makeshift classroom in a school compound in Gaza City, which is also serving as a shelter for displaced people. (AP Photo/(AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

In mid-January, soon after the ceasefire in Gaza was announced, Palestinian students rushed back into what was left of their schools. Until Israel broke the ceasefire in March, the United Nations estimated that over 150,000 Palestinian children filled Gaza’s classrooms for the first time since October 2023. The reprieve was brief, but it nevertheless represented something more than a pause in the carnage — or it seemed to, for children and their families who, facing the abyss, deemed studying in schools a worthwhile use of terrifyingly finite time. Displaced, dispossessed and under deadly assault for more than a year, Palestinians still somehow wanted to learn, to make sense of an impossible world.

In fact, they had never stopped. Even at the height of Israel’s onslaught, you could read reports on social media of a Palestinian doctoral candidate defending his dissertation in a bombed-out building. You could see photos of a master’s student defending his thesis in a tent where, presumably, a school or home once stood. The details of these stories are impossible to verify, given both the vicious campaign and Israel’s serial media blackouts. But the mere fact that these young people kept writing, learning and creating amid the annihilation of their families and their homeland should force us to think more seriously about what it means to receive an education.

Roughly six months after Israel’s initial bombardment began, thousands of miles away, a young Jewish graduate student at Columbia University joined a campus protest demanding an end to the genocide in Gaza, U.S. aid to Israel and the complicity of the country’s most prestigious universities. “We don’t want police brought onto campus to beat up people and arrest people for practicing our First Amendment rights in our name,” he said. “We don’t want Israel committing a genocide in Gaza in our name.” Making these demands did not come easily for him. “I was raised to be a Zionist,” he told a reporter, “to be a supporter of Israel, to believe that Israel was an important part of my identity.”

“Other people,” he said, “were born in refugee camps [and] watched their family get killed by the Israeli military.”

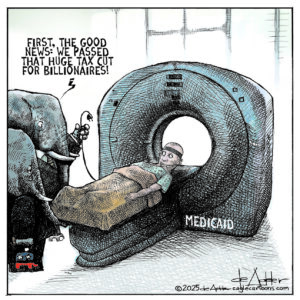

Biden wielded the muscle and thin moral valence, Trump the money and the deportation machine.

At Columbia, strangers soon became friends and ultimately comrades as the school unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on protesters. This, too, was a kind of education. It’s easy to forget that the encampments that started at Columbia — before spreading across the U.S. and then the world — began toward the end of the school year, when students were preparing for exams, writing papers, planning their summers. The encampments changed all that. Together, the protesters read books, discussed ideas, prayed, wrote press releases, and made arguments for the world to read and hear. Together, they faced harassment, violence, arrests and threats. And with the abduction of Mahmoud Khalil and others like him, protesters now collectively face political repression unseen since the second Red Scare.

All of this was initiated under the Biden administration and has continued under the current administration. President Joe Biden wielded the muscle and thin moral valence, President Donald Trump the money and the deportation machine. These experiences have no doubt changed all those involved. Some former protesters have understandably opted to lie low; others have redoubled their efforts, deepening their solidarity with one another and with Palestinians, becoming ever more resolute in their fight.

* * *

To a less sympathetic public, however, the fact that these protests began at elite private universities was cause for skepticism. For many — maybe most — Americans, such schools are not places for democratic politics but rather for the production of elites who, at best, manage our democracy from the top down, and at worst actively quelch it. By now we have all encountered an idea of elite universities as hotbeds of radicalism, where students soak up critical race theory by day and devour Judith Butler by night. This is, to say the least, a deranged distortion. Far more elite academics are driven by careerism than by socialism. In any case, even where the slightest traces of evidence for this caricature could ostensibly be found — in the humanities and social sciences — these would-be antagonists are mostly marginal to the contemporary university, whether measured by faculty governance, student enrollments or institutional clout. At most universities, it’s the vocationally oriented disciplines that command the highest budgets and wield the most influence: business and law and medical schools, computer science and engineering and health sciences departments, and so on. The costs of college tuition and the revenue-raising imperatives of university administration make this imbalance feel inevitable. This is just as true at Columbia as it is at the University of Houston.

Education has long had a fraught relationship to both elitism and democracy. As Helena Rosenblatt notes in “The Lost History of Liberalism,” what defined civic freedom in ancient Rome wasn’t just not being a slave, but being a citizen — far from a simple status. Cicero insisted that citizenship had to be achieved through hard work, discipline and learning the practice of liberalitas: a way of relating to fellow citizens founded on “mutual helpfulness,” which formed the “bond of human society.” “Selfishness,” Rosenblatt writes, “was not only morally repugnant, but socially destructive.” Citizens had to act liberally — in Cicero’s words, to “do good to one another” and “contribute to our part of the common good” — and this, in turn, required a certain kind of education in the liberal arts. Being free, in other words, was an art, one that was learned, not innate.

But this kind of education was not for everyone. Citizenship was less a realm of freedom than a way to define and sustain unfreedom. The ancients weren’t shy about this fact — the exclusiveness of self-rule was what made that society work. This was how the select few could “develop [the] intellectual and moral excellence” necessary to take part in self-rule. The masses, meanwhile, were to be schooled, Rosenblatt notes, in the “mechanical arts” that served “the baser needs of humankind, such as … tailoring, weaving, and blacksmithing.”

Something like this elitist spirit lives on at places like Columbia, but in inverted form: the disciplines privileged by administrators, parents, employers and many students are those that purport to meet immediate material desires rather than social and political ones. These institutions do continue the tradition of an elite liberal arts education, where one can, in theory, take courses on Plato and Fanon, but as with most universities, it’s the “mechanical arts” that reign supreme. Ironically, it’s within the labor movement — composed of the political descendants, in a sense, of tailors, weavers and blacksmiths — where the ethos of “mutual helpfulness” and a “humane attitude” is now most movingly cultivated. The realm of necessity, in other words, need not be antithetical to the kind of democratic education that was once the reserve of elites. Look no further than the SEIU, which denounced ICE’s abduction of Tuft’s graduate stuent Rümeysa Öztürk and recently celebrated the release of their union sister, declaring that “Rümeysa is free and she is free because workers stood up and demanded justice. … But our work is far from over. Rümeysa is free, but millions of other immigrants are not.”

Education has long had a fraught relationship to both elitism and democracy.

Indeed, in more recent history, education in the realm of necessity and in the realm of freedom appear intimately bound. Anyone who has picked up a copy of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Black Reconstruction” (1935) is immediately struck by its opening chapters, not least the chapter on “The General Strike,” which recasts emancipation as labor history instead of the political or legal history of old. Less commented on and no doubt less read, however, is his chapter on “Founding the Public School.” Du Bois saw Reconstruction as America’s only genuine attempt to achieve democracy, a moment he notably described as a time of the “dictatorship of labor.” This required the end of slavery and disfranchisement — but it also required mass education.

For Du Bois, education and democracy went hand in hand for reasons that echoed the elitism of the ancients. What distinguished him was his appreciation of the promise of social progress and self-transformation. In “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), Du Bois wrote of “the talented tenth,” an elite, educated stratum of Black people who were suited to lead in politics, culture and intellectual life. While Du Bois’s tenor grew more egalitarian over time, traces of this elitism persist in his writing on education and voting in “Black Reconstruction.” There he wrote of what he called the “eternal paradox” of democracy: that “in all ages, the vast majority of men have been ignorant and poor, and any attempt to arm such classes with political power brings the question: Can Ignorance and Poverty rule?”

Yet Du Bois also stressed the “consideration of the possibility that the great mass of people may become intelligent.” Education, he argued, could “bridg[e] the road from ignorance and poverty to intelligence and an income sufficient for civilization.” Rather than engaging with rancid ideas of immutable traits, Du Bois prioritized the historical constitution of postbellum social practices, and the material conditions needed to sustain civic rights that were made, not given. Labor’s march, for Du Bois, was a march for civilization. Left with nothing but the wounds of mass violence and dispossession, formerly enslaved people were nevertheless relentless. They wanted to read, to write. They wanted to reunite with their loved ones who had been sold off as property. They were no longer slaves; they were now eager to learn how to be free.

It is far too difficult to compare this history with that of the children and adolescents of Gaza — the two are too distant in time, moral worlds and material conditions. But in both, we see the unyielding desire to learn, even at the edge of oblivion. You don’t need to be an existentialist to appreciate that, at the very least, to be free is to be a subject instead of an object, to be able to act decisively in the world rather than only be acted upon. For Du Bois, as for young people in Gaza and on college campuses around the world, by attempting to create a new freedom in the world, they came to know the world as it was; with some courage, they could imagine it as it could be.

* * *

Democratic education is never pure; it cannot be conceived as part of an autonomous “life of the mind.” It’s embedded in the daily institutions and operations of politics and power — namely in the workplace. Universities are workplaces, albeit distinctive ones, where knowledge is pursued for the market and for its own sake. For many students, the dueling drives of instrumental and critical reason make for explosive politics. What makes donors, university administrators and the White House so anxious and enraged are the unraveling contradictions of elite institutions predicated on exclusivity that are also populated by students demanding universal human freedom, be it in the labs at Columbia or in the Gaza Strip.

It’s almost too apt that Columbia recently expelled Grant Miner, a medieval literature student and president of UAW Local 2710 — representing Columbia’s graduate student workers — the day before union contract negotiations were set to begin. Here was a graduate student in the liberal arts, a lover of what seems so remote from the compulsions of economic life who was now charged with leading fellow students in an age-old conflict between capital and labor. What’s more, Miner was one of many Jewish students who took part in the encampment protests for Gaza last year and continues to advocate not only for his fellow workers, but for the freedom of Mahmoud Khalil, for Palestine and for Columbia administrators to recognize that no appeasement will be enough for the Trump administration, which seeks to bend the university completely to its will.

To be free is to be a subject instead of an object.

The UAW, to its enormous credit, has denounced Miner’s expulsion not on the narrow grounds of violating labor law, but in defense of basic social freedoms. “Trade unionists everywhere, defenders of the Constitution, of freedom of speech, of academic freedom, and of the right of free association, should be appalled and disgusted,” the union’s statement declared. “If they can come for graduate workers, if they can arrest, deport, expel, or imprison union leaders and activists for their protected political speech, then they can come for you.” The old slogan that “an injury to one is an injury to all” was not, of course, an empirical fact, but a call to forge the kind of solidarity that could make it a social fact, giving workers the moral and political resources necessary for their self-emancipation.

This is an old struggle for the UAW, which was born in the fires of the Great Depression and saw dramatic growth after the Flint sit-down strikes of 1936-1937. Not unlike the anti-genocide protesters, workers occupied their workplaces: General Motors plants. While occupying plants, they played cards, wrote poetry, sang songs, put on plays and, notably, taught each other about the history of the labor movement.

To what end? Union recognition was certainly part of it, as was the end of petty employer tyranny and the inhuman conditions in plants. But GM workers’ ambitions, like student workers’ ambitions, reached much further. Joe Sayen, a worker who helped take over the Chevrolet No. 4 plant, exclaimed: “We want the whole world to understand what we are fighting for. We are fighting for freedom and life and liberty. This is our one great opportunity. What if we should be defeated? What if we should be killed? We have only one life. That’s all we can lose, and we might as well die like heroes than like slaves.” The UAW has not always covered itself in glory, but the union’s current expansive vision — one that unites medieval literature students with assembly line workers, Khalil and Tennessee autoworkers — shows us a promising way forward, one that sees the workplace not as a bounded domain of narrow collective bargaining but rather as a key site of a broader social conflict.

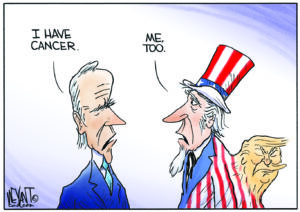

The most vehement attacks on higher ed have undoubtedly been those against the Palestinian freedom movement. And both the Trump administration’s threats and the Columbia’s speedy acquiescence shows that little really separates the vision of the White House from that of the university’s administrators. This presents student activists with a forbidding challenge, but they are hardly alone. Notably, STEM fields — which may have seen themselves as above the fray, transparently valuable to universities and markets in ways the liberal arts are not — have been the first to feel the financial burden of Trump’s assault on higher ed, and a key point of leverage in the administration’s push to purge university life of any kind of dissent.

At Harvard, where I teach, this has profoundly politicized a large segment of scientists, creating new social openings for both labor and Palestinian freedom organizers alike. It would be surprising if this were not the case at other universities as well. The Trump administration, in short, has unwittingly created the grounds for a potentially powerful alliance between scientists and humanists. Sometimes, as the saying goes, the boss really is the best organizer.

This kind of unity — this education in solidarity — may yet be tested as universities retreat into defensive positions. Duke economist Timur Kuran recently suggested that instead of “across-the-board spending freezes,” universities facing funding cuts should prioritize spending for “sane departments,” while punishing others “that have lost their way” and been “captured by post-modernists” (read: the humanities). In the New York Times, Columbia’s chair of biological sciences argued that without ample funding for STEM research, the university becomes “more akin to a high school or a local community college where you’re just teaching some classes without … bringing the frontier of knowledge into the classroom.” These are paths toward individual survival at a cost of broader social collapse.

Swearing you’re well-behaved and important won’t save you.

If Trump’s first months in office have taught us anything, it’s that swearing you’re well-behaved and important won’t save you. Veterans, firefighters, civil servants, National Parks workers, public schoolteachers, Social Security administrators and countless others who aren’t “post-modernists” have all faced a similar fate. This makes the threat that Trump poses all the more daunting, but it also gives labor a massive and urgent opening to forge solidarity.

Critically, the initial target of the administration’s assault — the public sector — has also been one of the labor movement’s few bright spots in recent history. Starting in the 1960s, public employees’ unions organized millions of new workers in the same decades when private-sector unions were bleeding members. As a result, the factions under attack are far better organized than many of their private-sector counterparts. Federal unions — many of them joining forces through the Federal Unionist Network — have been at the forefront of filing lawsuits and coordinating protests. Another coalition of public- and private-sector unions recently issued a joint statement denouncing ICE’s abduction of immigrant workers and calling on employers and local governments to “find their spines” and refuse to comply with federal orders. The statement condemned, in the same breath and with equal force, the kidnappings of farmworker union organizer Alfredo Juarez and Oztürk — further helping solidify solidarity across vastly different economic sectors.

While this convergence of coalitions is, for now, necessarily reactive and contingent, in the longer run it might not merely aim to restore what was lost under the Biden and Trump administrations, but instead help create something new. Despite various legal constraints on federal worker unions, their membership rolls have surged since Trump’s re-election. Local chapters of the American Association of University Professors — the quasi-union organization for college faculty — have likewise seen their ranks grow rapidly. At stake for all these workers are not only their own jobs, but also the general well-being of the people who rely on them for education, health care and social security; they, too, must be drawn into a broad coalition, especially as massive social spending cuts will almost certainly emerge from federal budget reconciliation negotiations.

Mobilizing across economic sectors and social segments can only be a profoundly social endeavor, in contrast to narrow pushbacks over this pot of science funding or that research grant. As any organizer will tell you, forging solidarity starts with listening: rather than telling people what their interests are or should be, you learn about their conditions, constraints, ambitions and motivations. That process reshapes both the organizer and the organized, and at its best, helps forge a vision not merely to restore some lost social order, but instead to create a new one.

* * *

It’s true that we have depressingly few recent models of such a merger of disparate peoples and struggles, at least in the U.S. But the remobilization of public-sector unions and their collaboration with private-sector ones — including some with unique social compositions, like the UAW — suggests a way forward. Joint statements, lawsuits and protests are clearly not enough. They are, however, the potential start of a coalition broad enough to undertake the kind of action that can reshape the political terrain: massive civil disobedience and general strikes.

Authoritarianism spares no one.

Antonio Gramsci once described three modes of social organization that could ultimately culminate into hegemony. The early process begins when workers in similar occupations recognize that their interests are linked. At a more advanced stage, broader class interests take shape, forming alliances that cut across industries. Hegemony, finally, is even more capacious. It transcends strictly class-based solidarity and combines various social fractions into a historical bloc based on, as sociologist Stuart Hall puts it, “intellectual and moral as well as economic and political unity.” That, he writes, is how a coalition can “propagate itself throughout society.” Trump wields power, but the MAGA right has yet to achieve hegemony — it relies too much on coercion, with little concern for gaining broad social consent. Indeed, the tariff fiasco is already fracturing his coalition. Meanwhile, oppositional forces remain somewhere between the first and second phase, as a growing number of people across different occupations are coming to see their shared fates: students and immigrants, educators and public-sector employees, the unemployed and disabled and elderly. If we are to do more than merely momentarily survive and actually build a social order worth living in, making a cohesive coalition of these social forces is a vital first step.

That task may be daunting, but it is not unprecedented. In its best moments, the history of labor has been a history of mutually inspiring freedom struggles. Eugene Debs credited abolitionists for making “it possible for me to enjoy what little liberty is left to me.” When the Wobblies belted the union anthem “Solidarity Forever,” they did so to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.” Martin Luther King Jr. closed his final speech, in support of striking sanitation workers, with stirring words first sung by Union soldiers: “Mine eyes hath seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” And when recently released ICE detainee Mohsen Madawi reflected on the encampments at Columbia, he drew on King’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” to declare: “The fight for the freedom of Palestine and the fight against antisemitism go hand in hand, because injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The civil rights struggle was and is a labor struggle, and the labor struggle was and is a social struggle for freedom.

There’s no going back to what we had before the current crisis. The challenges facing higher ed are by no means unique, as the broad attacks on immigrants and public-sector workers make plain. Authoritarianism spares no one. Only a broad social coalition can save itself, but this will take courage and time. For many, it will mean letting go of some comforting privileges. It won’t be easy — perhaps it won’t even be possible. But it’s the only thing worth trying. This is how we learn to be free.

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.