Don’t Abandon the WHO, Reform It

Even critics of the global health organization say that the United States’ withdrawal is a bad move for everyone. (Image: Adobe)

(Image: Adobe)

When Ebola swept through West Africa in the mid-2010s, Ashish Jha joined a chorus of health experts criticizing the World Health Organization’s response. The global health agency, these critics said, was slow to declare a public health emergency and to coordinate the responses needed to contain the deadly outbreak. The disease killed more than 11,000 people, mainly in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea.

“The most egregious failure was by WHO in the delay in sounding the alarm,” Jha said at the time, after he co-authored a 2015 report laying out “essential reforms.”

Such critiques weren’t new then, and they continue today. But Jha and other longtime WHO observers say that the latest pushback against the agency has gone too far. On Jan. 20, President Donald Trump’s first day back in office, the United States withdrew from the global agency, citing in part what Trump described as a “failure to adopt urgently needed reforms” and a “mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The administration also noted the “inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states.”

While the abrupt withdrawal has revived calls for reform at WHO that have accumulated over the years — proposals for term limits and political independence for the leadership, a narrower scope and a greater commitment to equity — it also highlights a precarious future for the agency, which for more than 70 years has responded to disease outbreaks, coordinated treatments and vaccines, and proposed public health measures. With bird flu and other global health threats looming, it is particularly pressing to have a functional global health organization.

“The fight we have set up is like, ‘Do we need WHO or not?’ I think that is the wrong question,” Jha, the former Biden administration’s White House COVID-19 response coordinator, told Undark. “The world is way worse off without WHO. But the world needs an effective WHO, and we should be able to talk about how to make WHO better without giving in to the temptation to destroy WHO.”

“The world is way worse off without WHO. But the world needs an effective WHO.”

The first Trump administration previously left WHO in mid-2020, early in the COVID-19 pandemic. (The withdrawal never went into effect; by the time a required 1-year notice period had expired, Joe Biden was in office and reversed the decision.) And some of Trump’s critiques at that time were not untrue, said Joanne Liu, a Canadian physician and former international president of Doctors Without Borders. That includes WHO’s role in COVID-19, how and when it officially announced a public health emergency, and how the WHO didn’t put much pressure on China for an independent investigation “that never happened, really,” she said.

But, she said: “We need a strong WHO. We cannot imagine a world without WHO.” It’s the only international health platform where each member country has a voice, she added.

With the more recent withdrawal, there likely won’t be a chance for a reversal until 2029 at the earliest. As such, the U.S. has removed a primary source of WHO’s funding, and experts say the move threatens the agency’s global legitimacy and clamps down on communications between the U.S. medical establishment and WHO authorities. There have been other repercussions, too: the Argentine government, led by Trump ally President Javier Milei, has already said it would also withdraw, citing COVID-related concerns. If other countries follow, Jha argues, there’s a risk WHO will not survive.

A day after Trump’s announced departure, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus posted on X, saying the agency regretted that decision and that “WHO plays a crucial role in protecting the health and security of the world’s people, including Americans.” Two weeks later, at a speech to WHO’s executive board, Tedros said: “We hope the U.S. will reconsider.”

At this time, as the fallout from the Trump administration’s withdrawal continues, health experts and officials outside the U.S. have been thrust into a defensive political climate, expressing commitments to work with the organization, said Jesse Bump, a global health researcher at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. WHO criticisms haven’t fallen by the wayside exactly, but covering the hole in the budget and instituting a hiring freeze have taken priority. Bump hopes discussions shift toward potential reforms, but that hasn’t happened yet, he wrote in an email: “There’s a lot of rudderless discussion without the U.S., even though it’s a tremendous opportunity to make progress.”

* * *

Leaders of WHO have reformed the organization’s policies in the past. In the early 2000s, for instance, after the SARS and avian flu outbreaks spread through Asia and beyond, killing or forcing the slaughter of tens of millions of chickens, WHO officials renegotiated a code of conduct called the International Health Regulations. In particular, they revised a set of contentious rules for countries’ rights and obligations when handling and communicating such cross-border public health emergencies.

But countries haven’t always followed those or other WHO rules, including during COVID, Bump said, and there’s no enforcement mechanism.

Even after the experience of COVID and its post mortems, WHO still hasn’t adequately addressed problems in how it declares international disease emergencies, said Michelle Amri, a global health ethics researcher at the University of British Columbia. In a new study, Amri and her colleagues found that in COVID and subsequent outbreaks like mpox, the criteria for such declarations haven’t been applied consistently, and they have appeared to some to be politicized. With each outbreak, WHO assesses the situation and declares an emergency based on several criteria: it must be an extraordinary event, a public health threat to multiple countries and require a coordinated international response. These formal declarations may come with additional consequences, too, like travel and trade restrictions.

Following the West African Ebola emergency that gained so many critiques from public health experts as a slow and limited response, WHO seemed to take note: In 2016, the agency quickly responded to concerns around the connection between Zika and birth defects, declaring a public health emergency just a few months after the reporting of those links (though the disease had already spread to more than 20 countries and territories).

But then, after Ebola returned to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018, WHO made the declaration the following year after multiple times deciding not to do so.

Despite inconsistencies in WHO’s applications of its public health emergency criteria, these cases seemed to mark an improvement over the West Africa Ebola outbreak. Nevertheless, some critics still saw flaws in those responses. Liu, for instance, was at the time the international president of Doctors Without Borders, and she said that WHO overcorrected when Ebola hit the DRC: The agency deployed a massive amount of financial resources, “to a point that they were not able to follow up that deployment,” citing an estimate of unaccountable expenses that may have been as much as half a billion dollars, she said. The agency set a precedent, too, growing to become not just a standard-setting institution but a medical humanitarian organization.

Because of WHO’s growing role in that capacity, even before COVID, the organization had an expanding scope, some experts say, encompassing both a normative mission — setting health guidelines and coordinating responses — as well as an emergency and humanitarian mission, alongside groups like Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross. Now, according to WHO’s website, its mandate includes not just responding to health emergencies but also promoting universal health coverage and addressing inequalities affecting health, like housing, education, and food insecurity. The mandate also includes issues like mental health promotion, “human capital across the life-course,” and climate change in small island developing states.

WHO still hasn’t adequately addressed problems in how it declares international disease emergencies.

“It has an overly broad mandate,” Jha said. “For the size of the organization, its financing, its technical capability, it is not able to execute on that broad set of missions as effectively.”

The agency sometimes adds new issues to its mandate, he added, and when that happens, it has to then follow those issues to ensure its authority on them. For example, WHO now has people monitoring the health risks of excessive screen use, but it’s not clear whether they bring anything unique to the table on this topic, compared to other public health organizations. “Every organization should know what they don’t do,” Jha said.

Els Torreele, an independent global health researcher and adviser who previously worked at Doctors Without Borders, agrees that WHO is spread too thin, given its budget, and that it should be more narrowly focused. The agency’s members keep expanding the scope, she said, but “there is no sense of prioritization.” It should be focused on where it’s needed most — norm setting — rather than its own humanitarian operations and clinical trials, Torreele said, which in some cases has it duplicating what other groups are doing, creating confusion.

It is chaotic when outbreaks emerge, Torreele said. “It’s important that there is some coordination and clarity about what the priorities are in terms of health,” she added. “But going in and opening a treatment center or setting up a clinical trial — no, that shouldn’t be their role.”

* * *

Wrangling such a large organization isn’t exactly straightforward. The WHO must bring together 194 member states — now 193 with the U.S.’s withdrawal — from all over the world to address evolving global health concerns. That geographical breadth inevitably spurs geopolitical questions at the organization. First, WHO’s executive board, responsible for setting WHO agendas and nominating the director-general, has considerable influence. It includes health representatives with three-year terms from 34 countries, including many wealthier, more influential ones, such as China, South Korea, Australia, Canada, and until recently, the U.S.

Some of these same countries influence the priorities of WHO through their funding of the organization. The U.S., one of WHO’s founding members, has delivered the biggest source of funding, and before its withdrawal it was on track to provide about $260 million during the 2024-2025 biennium, while China is spending about $180 million in that period. Germany, the United Kingdom, the Gates Foundation and Rotary International are also large backers.

During the first years of COVID, WHO faced a difficult balance between its member states, Amri said, and critics have had valid concerns, including some related to China. For one, if WHO were to investigate the COVID lab-leak origin theory, it could have only done so with cooperation from the Chinese government, which wasn’t always forthcoming. Secondly, since 2016, when tensions increased between China and Taiwan, the latter has been excluded from WHO, even as an observer. In 2020, a senior WHO official was caught on video in an interview, seemingly dodging questions about the situation. That widely shared video only reinforces broader concerns about WHO, Amri said.

WHO’s sometimes slow response to crises isn’t just a structural problem in the organization, said Bump, the Harvard health researcher. If WHO says or does something that a country’s government doesn’t like, it can lose access or funding. “They’re like a shell-shocked bureaucracy, where they don’t have courage because they don’t have power, and they’ve been punished for using it,” he said. This is a common tradeoff in the health world, Bump said, and that’s why the Red Cross never says anything about, say, a country’s dictatorship or human rights violations, so that it continues to have access to patients there.

In a related issue, some other global health experts suggest that the senior WHO leaders lack courage partly because they seek reelection, and annoying WHO member states can imperil that goal. That’s why some experts are advocating for WHO leaders to be term-limited, to ensure their political independence. However, such reforms might not be sufficient, Bump said.

“They don’t have courage because they don’t have power, and they’ve been punished for using it.”

Ultimately, member countries need to be able to collaborate and give WHO some enforcement authority, such as to coordinate the sharing of vaccines and vaccine technologies. But that’s something governments haven’t yet done.

Administering such an organization with members with disparate priorities and unequal power also makes another of WHO’s many goals difficult: health inequities, often defined as differences that are avoidable, unnecessary and unjust. Here, critics say, the agency’s efforts have also often fallen flat. For example, a few years after World War II, WHO failed to follow its own committee’s recommendation to “encourage production of penicillin and to ensure its equitable distribution to all countries,” according to a 2024 paper in PLOS Global Public Health.

In her research, Amri and her colleagues studied WHO texts between 2008 and 2016, only to find inconsistencies in how the organization approaches health inequity. It’s an inherently challenging problem, she told Undark, because “health equity is really a complex and nebulous term, it has so many values inherent within it, it’s a moral concept, so it’s not so clear-cut.” Sometimes health equity can mean reducing health gaps or seeking a baseline level of health for all, and other times it can involve a perspective that considers structural issues like poverty and politics.

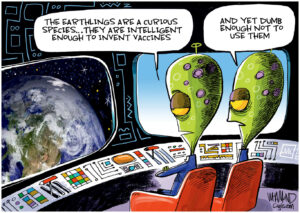

During the COVID-19 pandemic, WHO didn’t meet its own equity goals, at least in terms of vaccine equity. Many critics perceived the U.S. and other wealthy nations as hoarding vaccines when they first became available, for instance, which amounted to a “shared failure,” according to Stephanie Psaki, the U.S.’s first coordinator for global health security, a position created by the Biden administration that is now vacant. Leaders in Africa, Central America, South America and elsewhere decried the persistent vaccine gap.

“Globally, we did not do a great job, especially in terms of the speed with which we were able to get vaccines and other countermeasures to low- and middle-income countries,” Psaki said. “We got them there eventually.” The U.S. government donated hundreds of millions of vaccine doses, she said, “but there was too long of a delay.”

Wealthy countries with major pharmaceutical companies also resisted calls to waive patent rights and share vaccine technologies. The result was that people in rich countries received 16 times more vaccines than poorer ones per capita, a 2021 Financial Times analysis showed.

Meanwhile, the WHO-backed COVAX program was designed to accelerate the development of vaccines and guarantee equitable access to every country. It was intended to provide 2 billion doses worldwide by the end of 2021 and 1.8 billion doses to poorer countries by early 2022, but it did not meet those targets. “The U.S. opted out, China didn’t join, and then the rich countries hogged all the stuff for themselves,” Bump said. WHO had a plan, he added, but “didn’t follow it.”

* * *

For WHO, a challenging road lies ahead, as it now has a substantial budget gap left by the U.S.’s exit. The agency has been working to “diversify its donor base to reduce reliance on the few traditional donors,” according to a statement that WHO spokesperson Carla Drysdale asked be attributed to the organization. The WHO is “going through a prioritization process” and it has instituted a raft of other measures, like limiting hiring and travel, the statement continued.

At the same time, the organization has much to address, including the ongoing mpox outbreak in Central Africa, bird flu in the U.S. and a mysterious disease emerging in Congo. Now the Trump administration has directed the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to cease communication with WHO, which means that American officials likely aren’t sharing bird flu information with international authorities, and the CDC is in the dark about the spread of mpox, of which there have been four known cases in the United States so far, and which are not linked to each other but involved people who had traveled to Central or East Africa. The U.S. funding cuts have also disrupted measles vaccination campaigns, even as an outbreak spreads in West Texas, New Mexico and neighboring states.

Over the past several years, WHO members have been negotiating a pandemic agreement, which would ensure that in future pandemics, a fraction of vaccines, tests and personal protective equipment would be equitably shared. However, the original deadline for the treaty passed in 2024. That has been extended, but the agreement is unlikely to move forward, especially without support from major players like the U.S., Bump said. Furthermore, he points out that language addressing inequities have been significantly watered down regarding the sharing of research and technology.

In the short term, WHO will presumably try to mitigate damage from the U.S.’s withdrawal, Torreele said. In the longer term, she hopes the shock of the situation will have a silver lining, encouraging WHO to reform and focus on its core mission.

“If we are in this time of crisis and big geopolitical shifts, can we grab that opportunity to bring back health as a human right, as a collective, solidarity-based thing?” Torreele asked. “That would be fantastic.”

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.