Dawn of the Fediverse

The end of Big Social Media could be near. The time is now to push for a publicly owned and controlled alternative. Web 3.0 is the next generation of internet development. Photo by Parradee / Adobe Stock

Web 3.0 is the next generation of internet development. Photo by Parradee / Adobe Stock

It can be difficult to recall, but the early 2000s were years of enormous possibility for the young internet, and for social media above all. Before the rise of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, an ecosystem of small networks flourished. This not only included bulletin board system web services, but also a plethora of budding social media networks like MySpace, Bebo, Cyworld and Grono.net.

Yet as today’s brand names grew, they made a fateful decision: They rejected interoperability, choosing to remain sealed off from each other. Facebook and Twitter built walled gardens to keep us locked into their services, unable to slide into other applications and platforms. The format ensured the internet of today was dominated by behemoths. A few networks to rule them all.

This was always a business decision, not a technological one. Had they wanted to, it was possible for emergent networks to “interoperate” and allow users on Facebook to make “friends” with users in other social media networks. But doing so would have limited the benefits of the “network effects” that proved so profitable to the Big Social Media corporations. If they could build features that manipulated people into spending more time on their network, and thus create more ad impressions, they did.

The result is a global society with only a few social networks containing billions of users. This has created enormous social problems that are often obscured by our focus on the personal idiosyncrasies and pathologies of these companies’ CEOs, rather than the structural problems with Big Social Media in general, and how it might be transformed to better service the global public.

This challenge is not an academic exercise, but a practical matter that is being addressed here and now, as hacktivists and hobbyists around the world build collectively owned and interoperable social networks. Indeed, the outlines of a new system are visible in the emergent architecture of the Fediverse, short for “federated universe,” which previews free and open source social media hubs that allow people and communities to build, maintain and modify their own networks, according to their own rules. The young Fediverse already encompasses user-owned and -run social networks that serve millions of people. Though nascent, they prove that a different world is possible.

The result is a global society with only a few social networks containing billions of users.

Behind the smoke created by headlines and social media debates about Elon Musk, a policy framework for this Fediverse is rapidly coming into view. In 2019, Sen. Mark Warner introduced the Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching (ACCESS) Act, which would require greater interoperability. In Brussels, European Union regulators have passed the Digital Markets Act that is set to (at least partially) mandate social networking interoperability among the social media giants in the coming years.

These bills are wedded to a capitalist framework that will keep the deep problems associated with Big Social Media intact. However, they also present the public with a golden opportunity to press for a full-scale reconstruction of social media as a democratic digital commons — a more hopeful vision that draws on the Fediverse as a model for a radically egalitarian future.

* * *

The problems with current social media models are numerous and well-known. The Big networks’ ability to ban or de-amplify content is of deep concern across the political spectrum, especially given their close relationships to the U.S. national security state and its allies. For years, Facebook worked with the Israeli government to censor Palestinian voices, while content moderation and other staff for Meta, Twitter, Google and TikTok often feature ex-national security agents advising tech platforms on how to handle what it considers mis- and disinformation. The Twitter Files have provided further evidence that politicians, powerful governments and corporations routinely apply pressure on Big Social Media networks to censor users.

Much of the rest of the world, meanwhile, finds itself in a state of digital colonialism, in which mostly U.S.-based transnational tech corporations own and control the core components of the digital ecosystem, while actively preventing interoperability in order to monopolize the market and orient their services to maximize user engagement, ad impressions, and thus power and profits.

And what profits! In 2021, Meta reported $117.9bn revenues and YouTube $28.8bn. Twitter took in $5bn, TikTok generated $4.6bn, and Snap generated $4.12bn. Google, Facebook, and Amazon currently take over half of global online ad spending, a state of affairs that has led some countries to propose or enact social media taxes negotiated between the tech giants and local media. Beneath these numbers, social media platforms cultivate a toxic “influencer economy” to generate user engagement and revenue, whereby popular social media personalities peddle products for corporate brands. This model is based on a top-down pyramid structure in which the 95% of revenues go to just 5% of influencers. In the U.S., 86% of young people are so-called “aspiring influencers” — the fourth most popular career aspiration among American youth.

And yet, abolishing corporate-owned and ad-driven media is a virtually nonexistent topic of consideration among digital justice advocates, who often instead campaign in favor of weak reforms such as better content moderation and non-targeted advertising on corporate platforms.

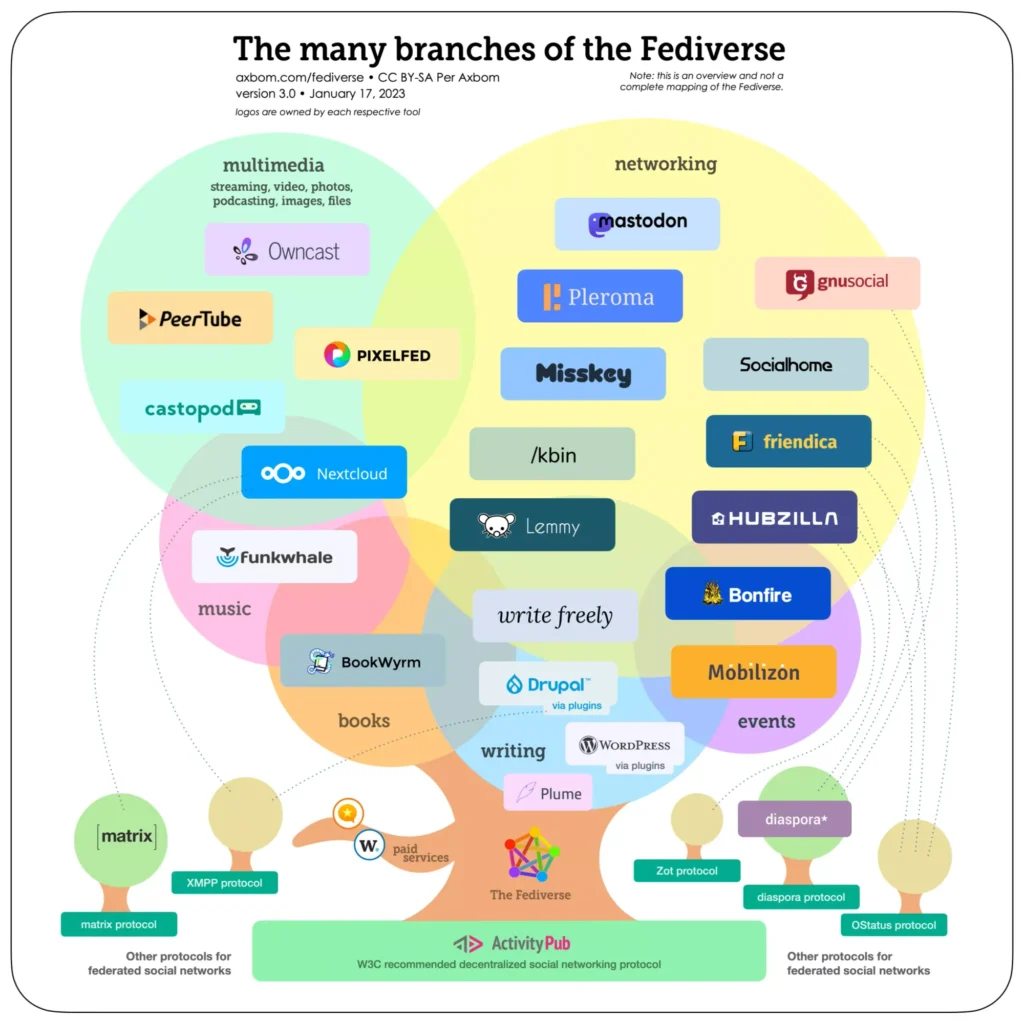

Against this backdrop stands the Fediverse. As its name suggests, the Fediverse is a “federated universe” of interoperable social networks, some of which are designed to replicate Big Social Media counterparts. Mastodon and Pleroma are much like Twitter. PixelFed is similar to Instagram. PeerTube resembles YouTube. And Diaspora is like Facebook. The networks use a common set of rules, called a protocol, so that users can interact with each other across participating networks.

People have most likely heard of Mastodon — a sleek, easy-to-use alternative to Twitter launched in 2016. Since Elon Musk took over Twitter, over a million new people have joined Mastodon, bringing its total user base to between 6 and 9 million users, with at least 2 million active users. (By comparison, Twitter has about 368 million active users; Facebook has close to 3 billion and TikTok over 1 billion.) Many social media personalities now list their Mastodon username as their Twitter name, and some high-profile celebrities have fully left Musk’s Twitter for the alternative with the elephant logo.

While Mastodon is very similar in style to Twitter, there is a major difference. At its core, Mastodon is not owned or controlled by any one person or network. Rather, it is a set of interoperable social networks called “instances” that set their own rules and voluntarily interact with each other.

You can use Mastodon in two places: through a web browser (e.g. on a desktop or laptop) or through a mobile app (e.g. on a tablet or smartphone). When you log into your account, you can view three timelines: the Home timeline, which shows the posts of everyone you follow; the Local timeline, which shows posts by your local (Mastodon.social) feed; and the Federated timeline, which shows the posts from all Mastodon servers from the people you follow. You can also make a “list timeline” that features a subset of people you follow. It’s up to you which timeline you want to tune into.

Content moderation is handled by instance administrators and individual users. Instance admins have tools to moderate users (e.g. freeze, limit or suspend accounts) or block other instances, websites, etc. Individual users can also mute or block other individuals or instances. This gives groups and individuals the means to filter what they see. While algorithmic filtering can be built into the servers (instances) or clients (apps used to access the platform), at present, Mastodon instances and apps do not appear to offer it. While this feature could be built – and even customized by individuals and communities – at present, posts in your timeline appear in chronological order.

Critically, the Mastodon software is licensed as Free and Open Source Software under the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL). This means if members of the public want to change some of the platform’s features, they can “fork” the source code and make a different version. The open source nature of the platforms also makes it hard to impose ads on users through the software, as the public can always take an ad-driven platform’s source code, strip out the ads and deploy it without the ads.

If members of the public want to change some of the platform’s features, they can “fork” the source code and make a different version.

A platform called Hometown provides a nice example of a Mastodon fork. Hometown is an ad-free Mastodon modification built for small, tightly-knit communities who want to keep their posts from proliferating across other instances in the Fediverse. With Hometown, users can make local-only posts that won’t broadcast out to other instances on the federated timeline. This allows members to share inside jokes or discuss things they don’t necessarily want the outside world participating in.

While “forking” the Mastodon software requires considerable programming skills, services like Masto.host can offer a user-friendly hosting so that you can run your own instance, even if you aren’t a computer programmer. This allows you – or people you might want to co-administer your network – to set your own rules, such as what kind of content is permitted, policies for suspending or banning accounts, and so on. The cost, if shared equally among users, is fairly low, ranging from $1.20/month for the lowest capacity (~5 users) and to 4.5 cents per user for the highest capacity (~2,000 users).

Anyone who uses Mastodon can not only communicate with other instances on the Mastodon network, they can also communicate with any network implementing the same protocol to communicate across networks. In the Fediverse, ActivityPub is the dominant protocol. A Mastodon user can follow or post a comment under a PeerTube video without having to join PeerTube, because they both use the ActivityPub protocol.

Mastodon and the Fediverse uniquely offer a Free and Open Source, decentralized alternative to Big Social Media, which explains why Elon Musk has been so dismissive, deriding the upstart network, stating, “If you don’t like Twitter anymore, there is awesome site called Masterbatedone.” In what appears to be an effort to quash competition, his programmers have also flagged Tweets with links to Mastodon as “potentially harmful” and cut off the developer community’s access to Twitter’s API – technology that can be used to help Fediverse users find and follow their Twitter followers on Mastodon.

* * *

The Fediverse is an exciting place full of possibility and promise. But it is also very young, and the current prototype has challenges.

For instance, much like Twitter, Mastodon does not currently feature end-to-end encryption for direct messages (DMs), but its developers are working on building that feature. Nevertheless, even with encrypted private messages, your behavior (such as when you login in, what you post, etc.) can be monitored by your instance administrator. Moreover, posts in the Fediverse can be “scrapped” (i.e. the posts are systematically collected) by third party entities such as corporations or national security agencies.

Centralized social media platforms are better equipped to detect unusual activity, such as scrapping, and limit third party scrappers they do not condone. (Nevertheless, Google indexes public posts of Big Social Media and police have been given access to Big Social Media’s databases of public posts.) But because decentralized networks are isolated from each other, it’s more difficult, if not impossible, to block scrapers. Mastodon has been scrapped multiple times by academic researchers against the consent of some members. For all we know, it’s scrapped by social media surveillance tools in the hands of the police, the NSA, the Chinese Communist Party and others.

According to Christine Lemmer-Webber, co-author of the ActivityPub protocol, there’s no way to stop public timelines from being scrapped. “We should not pretend that we are able to prevent what we cannot, because if we do so, we actually put our users at greater risk,” she told me in response to the scrapping issue. Instances could implement a request not to be scrapped, similar to robots.txt, but they cannot stop it.

This means at present, if you post something in the Fediverse, until there’s an end-to-end encryption feature, you should consider it public and part of multiple third-party repositories. It also means if you select a pseudonym for your identity, you’re vulnerable to being doxxed by a skilled adversary.

There are ways to improve privacy in the Fediverse. For example, a peer-to-peer social media network under development called LibreSocial would drastically decentralize network data hosting. On this model, each user would reserve a portion of their device’s memory to store the data shared on the network. Yet access to that data would be decrypted according to user wishes in their settings. So, if you make a post set to “friends-only,” then only your “friends” can decrypt the data.

At present Big Social Media companies like Meta can still view friends-only posts, also opening up the capacity for intelligence agencies to get access. LibreSocial’s model would then increase public privacy for friends-only posts, because there is no “man-in-the-middle” to access the data. Technologies like LibreSocial could thus further decentralize social networking by distributing the network data further to the edge.

Lemmer-Webber notes that projects like LibreSocial can also be integrated into the Fediverse, and she thinks that ideally, society would build interoperable and collectively self-hosted networks.

“There’s no reason our tech can’t handle that,” Lemmer-Webber told me.

* * *

While the Fediverse proves that a different social media landscape is within our grasp, it cannot scale up and overtake Big Social Media without supportive policies in place. New policies from the EU and U.S. guarantee that some form of social networking interoperability is coming, but they have little critical engagement from the grassroots level.

In my view, the digital justice movement should be contesting the coming shakeup of social media to make sure it is not captured by corporate interests.

The EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) has already been passed and is set to implement some form of social media interoperability requirements in the coming years. The U.S.’s ACCESS Act is still just a proposal, but the bill may pass eventually. Both of these acts mandate some degree of interoperability. However, both acts will likely favor Big Social Media, as they only mandate that the super-large networks offer interoperability with other networks, and they keep the privatized, profit-seeking model of social media intact.

For example, under the DMA, social networks would have to offer the option for other networks to “interoperate” with it. Let’s say I start up “Littlegram,” and I want to get new users. I might want to interoperate with Instagram, this way if new people want to join my network, they can still interact with their Instagram friends. Instagram cannot block my network’s request to interoperate with it – it must offer the option.

Yet the DMA’s mandatory interoperability option would only apply to social networks with “a market capitalization of at least 75 billion euro or an annual turnover of 7.5 billion,” and “at least 45 million monthly end users in the EU and 10,000 annual business users.” In the U.S., the ACCESS Act of 2022 has a similar threshold of 100 million active users in the United States.

Under these bills, smaller networks like Littlegram would be incentivized to interoperate with Big Social Media networks because most new members would likely want access to their friends and other users. Yet similar other smaller networks competing with Littlegram, such as Smallgram, would have less of an incentive to interoperate with each other, especially if they are competing for eyeballs (and therefore profits and revenues). Meanwhile, the Big Social Media networks would have an advantage if most small networks interoperate with them but not with each other. The Big Social Media networks would then keep the largest user bases, incentivizing people to be members of their networks.

At present Big Social Media companies like Meta can still view friends-only posts, also opening up the capacity for intelligence agencies to get access.

In fact, if a large variety of new small companies spring into existence, they may go through the same process that happened in the early 2000s: many companies to start, and a gradual concentration towards a few of the growing “small” networks. Moreover, corporations like Microsoft and Google might start bundling their own social media platforms into their “productivity” suites, while corporations like Disney, Netflix and Spotify might create social media networks that connect to their products and features.

Meanwhile, the incentive to manipulate users to stay hooked in smaller networks instead of competitors to Littlegram would still exist. So too would the earth-destroying harms from advertisements and the influencer economy alluded to earlier.

The prospects of a “corporate Fediverse” unleashed by new legislation is therefore of deep concern.

Instead of going this route, digital justice activists could push policymakers in a different direction – one which ensures communal ownership and control over the social media landscape. To accomplish this, we could pass new laws to support a democratic social media commons.

First, we could drastically lower the threshold to mandate an interoperability option. This would ensure social networking is broadly interoperable. Open sourcing software and mandatory “internal” interoperability (e.g. forcing Meta, TikTok and Twitter to fully open source its platform software and offer the option to create independent “instances” much like Mastodon) could also be used to transition Big Social Media to a federated landscape.

Second, we could ban forced advertising so that it’s no longer built into the platform or legally forced on people through “influencers.” This would remove the influence of corporations on media content and social network policies. By cutting out the constant psychological inducement to live a consumerist lifestyle, it would also bring us closer to environmental sustainability.

Third, we could publicly fund the social media commons. To accomplish this with democratic accountability, citizens could be given tax vouchers – much as Dean Baker recommends for artistic and noncommercial media – which could then be applied to their favorite organizations for research and development, content moderation, hosting, connectivity and even news media and entertainment. Those organizations could feature workplace democracy and run at cost on a nonprofit basis instead of running as private enterprises that seek market expansion and concentrate wealth into the hands of rich executives and shareholders.

Since the Global North has most of the world’s resources, we could provide resources to people in the Global South to help develop the establishment of social media commons. This could dovetail with a larger, globally coordinated ecosocialist Digital Tech Deal that rolls all forms of social justice and environmental sustainability together.

With the Fediverse, we have a functioning prototype for a better social media system. Yet new laws are already in place to keep capitalist “solutions” intact. It’s high time to push for a social media landscape that is owned and controlled by the people instead of corporations and governments.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

Great article, thanks for this in-depth look at the Fediverse!

One minor language glitch, I think you may have meant "scraping" not "scrapping"?