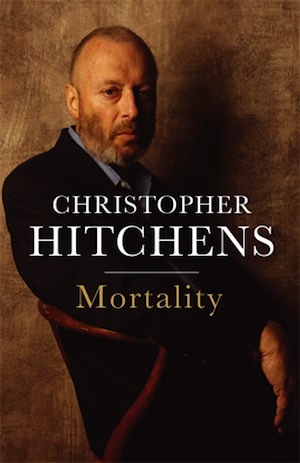

Christopher Hitchens: ‘Mortality’

“Mortality,” Jeff Sharlet writes of the late Christopher Hitchens’ small, posthumously published book of essays, composed while the author was dying of cancer, is death-writing “at its most generous and most human: just another man dying, making a joke and telling a story.”

“Mortality,” Jeff Sharlet writes of the late Christopher Hitchens’ small, posthumously published book of essays, composed while the author was dying of cancer, is death-writing “at its most generous and most human: just another man dying, making a joke and telling a story.”

It is not a collection of Hitchens’ best work, Sharlet writes, as it sometimes trades the biting wit for which Hitchens was famous for a kind of “stand-up shtick.” But the man should be forgiven, as the progression of his disease left him little to no choice in the matter, and should as well be applauded for penning his dispatches on dying until the very end.

“Mortality” features a foreword by Vanity Fair Editor-in-Chief Graydon Carter and an afterword by Hitchens’ surviving wife, Carol Blue.

— Posted by Alexander Reed Kelly. Follow him on Twitter: @areedkelly.

Your support matters…Jeff Sharlet at Bookforum:

Mortality, a posthumous collection of Christopher Hitchens’s short essays on living with terminal esophageal cancer—“a distinctly bizarre way of ‘living,’ ” he emphasizes, “lawyers in the morning and doctors in the afternoon”—is an odd little book, neither fully a cancer memoir nor a meditation on the meanings we attribute to the disease. Though indebted to Audre Lorde’s classic The Cancer Journals and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (it’s hard to write about the experience of cancer free of the influence of either, regardless of whether one has read them), Hitchens cites neither. The voices he summons to his decline are mostly those of ironists: Ambrose Bierce with his Devil’s Dictionary, John Updike, Kingsley Amis. As the book progresses—if that term can be used to describe its author’s disintegration—it becomes crowded with interlocutors. Many of them are more earnest, to greater and lesser effect. The late philosopher Sidney Hook describes his own terminal disease; Hitchens describes Nietzsche’s; “Dulce et Decorum Est,” Wilfred Owen’s World War I poem of death by gas (a fate as “obscene as cancer” in Owen’s telling), is reproduced nearly in full; and YouTube sensation and best-selling author Professor Randy Pausch reveals through his video The Last Lecture, in Hitchens’s estimation, “exactly how not to be an envoy” from what Hitchens comes to call “Tumortown.”

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.