Charisma Isn’t Everything

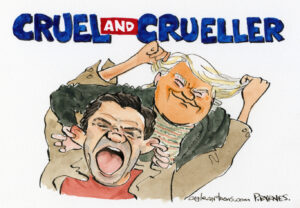

Karl Rove set out to build an eternal Republican majority. In the end, he managed two terms for a mediocre president.WASHINGTON — Karl Rove and I have something in common: Both of us treasure a campaign poster from the 1972 elections.

The poster, which Rove hung in his Texas political consulting office, was from the re-election campaign of Illinois Gov. Richard Ogilvie, a reform-minded Republican moderate. It was adorned with the slogan: “Charisma Isn’t Everything.”

No doubt our shared lack of charisma drew us both to this campy relic. But Ogilvie’s progressive Republicanism spoke more to my political affections than his. Rove will be remembered for an approach that drove millions of Republicans and independents of Ogilvie’s stripe into the Democratic Party.

With Rove leaving President Bush’s White House, much will be written about his style of politics. But the key question is whether Rove succeeded on his own terms.

His objective was grand. In an interview in 1999, Rove predicted that the 2000 election would be like that of 1896, when William McKinley created a new Republican majority that went on to control the presidency for all but eight of the next 36 years. As Rove saw it, McKinley built a dominant party by changing its message and appealing to new voter groups. George W. Bush would be this era’s William McKinley.

Bush would do more than just refurbish the coalition that Ronald Reagan built, the back-to-the-future fashion in conservative circles now. Bush offered “compassionate conservatism” as a corrective to the coldhearted kind. He laid heavy stress on education reform, stealing one of the Democrats’ best issues, and spoke warmly of Latino immigrants. Just as McKinley appealed to the new immigrant groups of his time, so did Rove and Bush understand the urgency of winning a significant share of the growing Hispanic vote.

Rove liked Napoleon’s adage: “The whole art of war consists in a well-reasoned and extremely circumspect defensive, followed by rapid and audacious attack.” He would defend Republicans against charges of hostility to the poor, public education and minority groups, and then attack Democrats with whatever came to hand.

This set up Bush’s victory over Al Gore in the U.S. Supreme Court, and from there, Rove went from strength to strength. After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, he used the national security issue to capture both houses of Congress in 2002. The terror issue, along with “rapid and audacious attack,” defeated John Kerry in 2004, and fortified the Republicans’ congressional majorities.

Yet just two years later, the bottom fell out. Bush could now become not William McKinley but Herbert Hoover, the man who ended the very Republican era for which Rove has such fondness.

What went wrong? Rove’s key missed opportunity came after 9/11. Instead of using the period of national unity that followed the terrorist attacks to build a broad Republican coalition rooted in Dwight Eisenhower-style moderation, Rove sought to create a narrower but tougher ideological majority willing to pursue such conservative dreams as the partial privatization of Social Security.

But a “51 percent strategy” leaves no room for error, and Bush proved very error-prone. Relentlessly attacking Democrats on national security meant that Bush’s opponents had no stake in his Iraq policy when things started falling apart.

And Rove may have drifted away from his empathy in 2000 for the middle toward an increasing stress on “turning out the base.” While Rove is a movement conservative shaped by the rise of a Southern-inflected Republicanism quite different from that of Richard Ogilvie, he is also an electoral pragmatist. In 2000, Rove adjusted to rhythms of the Clinton era and ran Bush as a far more moderate candidate than he actually was.

By 2004, Rove decided that the middle was overrated and he turned out Republican conservatives in droves. The bill for this game plan came due in 2006 when moderates and independents flooded to the Democrats and left Rove’s Republican majority in tatters.

Rove’s friends will say that, absent the Iraq war, his blueprint could have worked. But Hoover would have been fine, too, without that annoying Great Depression.

Paradoxically, Rove may have been too partisan and too ideologically committed to build an enduring partisan majority. His strategy of polarization called forth enormous feats of organizing by Bush’s opponents. In mobilizing Bush’s own base, Rove also mobilized an alternative coalition fed up with the politics of the right. In giving Bush’s enemies no quarter, Rove left behind an angry “mob” — his word from Monday’s Wall Street Journal interview — ready to strike when the opportunity presented itself, as it inevitably did.

Bush expressed warm gratitude to his “dear friend” on Monday, and why not? It took Rove’s genius to make Bush president. But the enduring Republican majority of his dear friend’s dreams still awaits its architect.

E.J. Dionne’s e-mail address is postchat(at)aol.com.

© 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.