Cesar Chavez: The Story of Ordinary People Doing Extraordinary Things

Diego Luna tells Truthdig he wanted to make a movie his Mexican-American son could look to for inspiration. Lionsgate

Lionsgate

Lionsgate

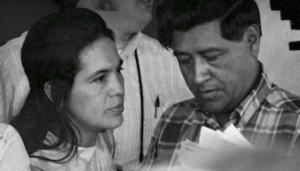

While spending time in Los Angeles, Mexican actor and director Diego Luna, known for movies including “Y Tu Mamá También,” “Milk” and “Elysium,” started seeing lots of Cesar Chavez. The union activist and civil rights leader’s image appears on murals around town and there is a major street named for him. Looking into the founder of the first union for farmworkers in the United States, Luna realized he didn’t know much about the man and went about finding out more. Luna’s son was born in Los Angeles, meaning he had a Mexican-American in the family, so he wanted to make a movie his son could look to for inspiration. Luna met with Chavez’s family and from his wife Helen Chavez heard how their oldest son felt his father’s activism took him away from the family. Although others had tried to make a movie about Chavez, the family went with Luna’s company Canana, founded with his childhood friend Gael García Bernal and producer Pablo Cruz.

To make “Cesar Chavez,” which arrives in theaters Friday, Luna got pressured to go with a big name star, such as Antonio Banderas, and to sex up the story somehow. Instead he hired Michael Peña to play Chavez and focused the movie on his founding the United Farm Workers with Dolores Huerta, and the famous grape boycott, as well as Chavez’s strained relationship with his son. Luna filmed much of the movie in Sonora, Mexico, using real farmworkers there as extras. Along with Peña, the cast includes Rosario Dawson as Huerta, America Ferrera as Helen Chavez and John Malkovich playing a grower who opposed Chavez.

In Berkeley, Calif., recently, Luna spoke about wanting people to think about where their food comes from, the union leader’s love for jazz and yoga, and how those who are running corporations are not going to decide on their own to make things better for others.

Emily Wilson: You’ve said your son was born here, so he’s Mexican-American, and you wanted to make this movie for him. But why is this the story you wanted to tell?

Diego Luna: I was thinking when my son gets to be 9 or 10 — I think that’s when I started caring a little about what the newspaper was saying, where I was living. I started to be confronted with a reality no one could protect me from. I come from a country of great contrast — of those who have and those who don’t. I remember at that age I started to go, “Oh my God, what’s going on?” And I remember there was an earthquake in Mexico that took my attention to, “Oh, my God, I’m part of something bigger.”

What I’m saying is I hope when my son goes through that, he can see a story about where he comes from that could inspire him. That’s the impulse I had to do this film. But also it’s a film that talks about a very simple thing I think we need to be reminded of which is that if we don’t get involved, change is not going to come. If we keep expecting politicians to come and change our reality, or if we keep expecting the great consciousness of those who run corporations to say, “You know what? Let’s do better for people,” it’s not going to come. Either we get involved, or we don’t have the right to complain.

EW: What was it about Chavez that first caught your attention and made you think he was special?

DL: I remember very vaguely the image of when he died and all these farmworkers walking with a wooden box where his body was. I remember looking at it and saying, “That’s pretty interesting. Who was that man and how can he move those numbers?” And the whole idea of him being buried in a wooden box — I’m going to go how I came, you know? I kind of liked that even when he died he was sending a message there was no luxury about death. It was a message about equality. I didn’t know who he was really, then being in the States I started noticing a lot of streets with his name, but I also realized I knew nothing and how little people in this country knew who he was. And definitely in Mexico, no one knows who he is — they all think he’s a boxer. So it was an attempt to bring our stories together. We as communities have allowed that border to divide us, and I mean Latin America from the Latino experience in this country. In many ways that border has alienated and separated us. Our stories should be shared, and cinema can definitely help for that. I think it’s kind of absurd that a country that normally celebrates almost every heroic story in cinema hasn’t celebrated this one. Why is Cesar Chavez not part of that list?

EW: What did you find out about him that surprised you most?

DL: What was surprising was how complex he was as a character — how far he is from the stereotype of a Mexican-American. I went to his office, and I remember going through his cassettes and finding there was more jazz than anything else. You’d expect this man to listen to ranchera or banda, but this guy loved John Coltrane and Miles Davis. He did yoga, he was a vegetarian, he read Gandhi — my point is that there’s so much complexity behind this character that it made it very rich to explore on film. In fact, it’s very unfair because a film lasts an hour and 45 minutes and you need 10 hours to bring all that complexity out. At least it’s an attempt to draw attention to a story that if you connect with it, you can go and look because the movement was recent, and there’s tons of film and recording and pictures to see.

EW: When you went to his family how did they react and what did they definitely want you to have in the movie?

DL: The thing is I wouldn’t be doing this film if I had no support from his family. It was after they agreed we started working on the film. We sat down with Paul Chavez, the youngest son who runs a foundation, and he was our connection with the family. I needed his family to be part of this because this is not a history lesson. This needs to work as a film and be entertaining and engaging with the audience and to bring that out, you need all the information that is not in books, that is not in recordings, the little intimate colors you need on film. For that I needed the family, and the most important person was Helen Chavez. Helen was supposed to come and just say hi and give us her blessing, but she arrived and stayed for two and a half hours and started talking and talking to the point I had to go back and rewrite because she gave me a lot of information that changed the perspective and point of view I was telling the story from.

EW: Like what?

DL: The most important was the father/son relationship. She told me about Fernando [the eldest son] leaving and how painful that was. I could tell because she was suddenly very affected, and I thought, “Well, that needs to be in the film.” Also I’m a father so I connected with that, and that to me matters. I went back and rethought a little the story.

EW: What are you most hoping people take away or get out of the movie?

DL: Many things, but I guess the most important — there are two. I really want people to get out of the cinema feeling they can do something. As Cesar said many times, this is the story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. You don’t need special powers and a cape to bring change — you just need to be clear about what you want, and never lose the curiosity to see who around thinks like you do. And if they don’t, why? It’s about never losing that curiosity and never letting that difference rule your life.

Another thing — if people get out of the cinema thinking what needs to happen for their food to get in front of them, I’ll be happy because that’s what we are talking about here. That’s what the boycott did. It was parents talking to parents, mothers talking to mothers and saying, “Behind that grape is the work of my son.” So if at the end of the film, you come out wondering what needs to happen for that carrot to get in front of me, we’ve done our work.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.