We Can Hold Police Accountable for Their Crimes. All We Need Are the People.

Policies that chip away at the power, protection and prestige that law enforcement enjoys are crucial aspects in the fight. Police officers watch protesters as smoke fills the streets in Ferguson, Mo., in November 2014. The fatal police shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown put Ferguson in the national spotlight, and since then, voters in several major cities have approved measures to create or strengthen civilian oversight of local law enforcement. (Charlie Riedel / AP)

Police officers watch protesters as smoke fills the streets in Ferguson, Mo., in November 2014. The fatal police shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown put Ferguson in the national spotlight, and since then, voters in several major cities have approved measures to create or strengthen civilian oversight of local law enforcement. (Charlie Riedel / AP)

This past July was the fourth anniversary of Black Lives Matter, the national network that was birthed from a hashtag on social media the evening that George Zimmerman was acquitted for the 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin. The Black Lives Matter movement grew exponentially after the August 2014 murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Mo., by police officer Darren Wilson, which led to the development of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL). This grouping of some 50 organizations has tasked itself with responding to the “sustained and increasingly visible violence against Black communities in the U.S. and globally,” according to the M4BL website. This violence occurs through disparate policies in areas such as health care, education, housing and employment. But the most visible disparity continues to be violence at the hands of police.

Since the failure of a St. Louis County grand jury to indict Wilson for the murder of Brown, the numbers of police officers arrested, charged, tried and convicted for egregious violence against black people has remained minute. More often than not, police officers responsible for brutality and death inflicted on black people are either fired or allowed to resign rather than face criminal charges. This is not justice. Depending on whom you talk to, neither is a prison sentence.

But something has to give. What could accountability look like for police officers in the United States? The recent police shooting of Justine Damond, a 40-year-old Australian woman living in Minneapolis, is a salient study in possible official responses to police terror in urban cities.

Damond called 911 about 11:30 p.m. on July 15 to report a possible sexual assault in an alley near her home. Minneapolis police officers Mohamed Noor and Michael Harrity answered the call to investigate. According to CNN, Damond [nee Ruszczyk] may have “slapped” the police car from behind once it arrived on the scene. Noor, who was in the passenger seat of the vehicle, says he was startled by the sound, and when Damond approached the driver’s side of the vehicle, he pulled his service weapon and fired over his partner, hitting Damond in the stomach. She would be pronounced dead at the scene. Neither the police vehicle’s dash camera, nor Harrity or Noor’s body cameras were turned on.

In case you were wondering, but were not sure, Justine Damond is white.

The responses of police and city officials to this case have been nothing short of amazing. Almost immediately after fatally shooting Damond, Noor and Harrity attempted to perform CPR on Damond and called for an ambulance—an occurrence as rare as a criminal indictment and conviction when the victim of police terror is black.

In the aftermath of the shooting, Minneapolis Chief of Police Janeé Harteau said she was “heartsick and deeply disturbed”; “I have a lot of questions about why the body cameras weren’t on”; “This should not have happened”; and “Justine didn’t have to die.”

Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges urged Noor to speak publically about what transpired that night, although Noor has a right not to do so. In other incidents of police terror, city mayors such as Hodges have been quiet as church mice, supporting officers and adherence to the timelines of official investigations. Not so in this case. Additionally, Hodges has publically criticized the shooting and asked for (and received) the resignation of Harteau, stating she no longer had confidence in Harteau’s “ability to lead us further.”

Although the response(s) to Damond’s death are hypocritical and thoroughly racist, they are a good indicator of what accountability for police terror could look like: Immediately calling into question the officer’s actions instead of providing “benefit-of-the-doubt” blind support and consequences from police leadership. It’s far from enough. But it is a start.

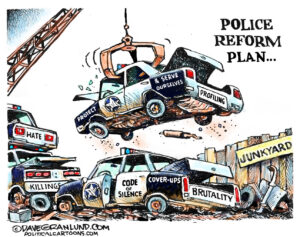

Policies that chip away at the power, protection and prestige that law enforcement enjoys are crucial aspects in the fight for accountability.

Campaign Zero, an effort born out of the Black Lives Matter movement and conceived of by DeRay McKesson and Brittany Packnett, provides another option: “zeroing” in on the protections provided to police officers through their employment contracts. Through the campaign’s Police Union Contract Project, the group has identified six ways that police, via their union representatives, have negotiated safeguards that keep cops across the country from accountability in varying ways: misconduct complaints get disqualified; officers are not interrogated immediately; officers are given access to information that members of the public don’t have; cities are required to pick up the tab on costs related to police misconduct; there is a lack of disclosure of an officer’s history/record; and there is a lack of strong, punitive consequences for officers who engage in misconduct.

A good example of this morass comes from Los Angeles. This past spring, L.A. County Sheriff Jim McDonnell wanted to provide the district attorney’s office with a list of 300 “problem” deputies. The deputies were found to have been guilty of various offenses via internal affairs probes. The offenses, classified as “moral turpitude” and “performance deficiencies,” ranged from tampering with evidence to falsifying reports to sexual assaults. A state appellate court ruled recently that McDonnell cannot provide the list to the district attorney’s office because it would be in violation of state statutes protecting officer privacy. Known as the “police officer’s bill of rights”—because the offenses were found via an administrative internal affairs process and not a criminal court—the hearings, offenses, outcomes, discipline (if any), and so on, are all considered to be part of an officer’s personnel file. Thus, the contents are private and cannot be shared, even in a court of law, unless an elaborate legal process is undertaken.

Dignity and Power Now (DPN), which was created by Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors to press for accountability from the L.A. Sheriff’s Department, disagreed with the state appellate court’s actions. So the organization created its own database of problem deputies to inform the public.

“We think the sheriff should appeal [the judges’ ruling] to the California Supreme Court, and we believe officers who are guilty of misconduct should be fired, and the [Los Angeles Sheriff’s] oversight commission should have more power so we can deal with and expose misconduct on the front end in the future,” says Mark-Anthony Johnson, director of health and wellness for DPN.

Johnson is not sure if DPN’s list is identical to McDonnell’s list of 300 problem deputies but thinks there’s some overlap. DPN compiled its list from public sources such as court cases and depositions, settlements and media reports. While DPN’s list may be embarrassing to some sheriff’s deputies, it is nonetheless legal.

Embarrassment, while not a replacement for justice, has its merits.

Back in 1980, the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression held a tribunal against police crimes in Los Angeles. At the time, James Simmons was a young law student. He remembers one police officer who was found guilty of “crimes against the people.” “We put up ‘Not Wanted’ posters throughout the inner city with this guy’s face on them,” says Simmons, “and not long thereafter, he left Los Angeles in search of new employment.”

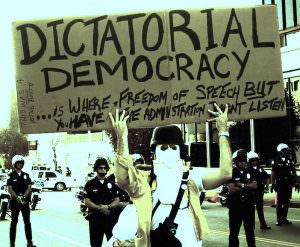

Asked if such a tactic should be used today Simmons says yes. “We should use whatever means are at our disposal, and apparently, the courts and the structure for police accountability are weak at the state level, if not nonexistent, so the community should have the right to hold those who commit crimes against them accountable, whether or not they are civilian or representatives of the government.”

Since that time, Simmons has gone on to be part of the organizing team of Justice Warriors for Black Lives, “a collaborative network of attorneys, legal workers, [and] non-legal workers working with community to provide workshops, training, policy development, and legal services” that grew out of legal support for Black Lives Matter protesters in the city.

In Chicago, the Black Youth Project, a member organization of the Movement for Black Lives, has called for the creation of “freedom budgets” in several cities that will transfer public monies from police to programs that create true community safety and allow communities the “freedom to thrive.”

The road to accountability of police will be long. It will also be hard, but it is not impossible. The political will for change is growing slowly, but it does exist. It must be nurtured and encouraged to grow. From tackling problematic police union contracts, to publicizing and embarrassing rogue cops, to “freedom budgets,” to making police personally liable for their misdeeds and yanking their licenses to be police officers, there is no shortage of tactics for accountability that can be pursued.

All we need are the people.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.