‘Bridge of Spies’ Film Review: A Movie for the Cold War Nostalgic

Starring Tom Hanks, it’s an efficient, exciting entertainment, but it’s also a Steven Spielberg movie, which usually means trouble somewhere. In this case, though, the irritations are minor, diffusely woven into the fabric of the film. Still image from IMDb

Still image from IMDb

Still image from IMDb

I never saw the Berlin Wall, but I did once gaze over the Iron Curtain. The actual structure, that is, not the Churchillian metaphor. In 1974, when I was 10 or 11, my father, then a major in the British Army on the Rhine, finagled a visit to a British-manned observation tower on the northern part of the heavily fortified border between the Federal Republic of West Germany and Soviet-controlled East Germany, a thousand-mile zip-fastener bifurcating Europe from the Baltic Sea to the southern Yugoslavian border. Seventy-some feet above the plain, we looked out over strips of minefields, triple lines of steel wire and fencing, troughs, dog-lanes — first ours, then theirs in virtual mirror-image — and finally, a mile or more away, their observation tower, their spooks, their snipers, looking back at us, eye to eye, Spy-vs.-Spy, on the front line of a war that never happened.

History, since the wall and the curtain came down in 1989, has been, shall we say, centrifugal, a never-ending hurricane of steel and glass, centerless, chaos-filled, confusing, nihilistic. In retrospect, it almost encourages nostalgia for the binary certainties and consolations of the Cold War, when you knew who your enemy was, and where he lived (behind that big fence, its purpose as much penal as defensive), and only fought him by proxy in places like Vietnam and Nicaragua, or in the shadow world of espionage, with the ever-looming threat of The Bomb keeping everyone in line. And, oh yeah, no God in the mix, no beheadings.

Well, I’m sometimes nostalgic for the Cold War, I’ll admit it, and judging by “Bridge of Spies,” so is Steven Spielberg. The late-Eisenhower ’50s he re-creates here (when the director himself would have been 10 or so, and deeply impressionable) are peppered with references to duck-and-cover drills in middle school, terrifying H-bomb documentaries that make kids cry, the then-new “under God” Pledge of Allegiance, and a Cold War reference on every newspaper or television screen that comes into view (he does rather lay it on). The Glienicke Bridge (referred to by the film’s title) from West to East Berlin, across which multiple U.S.-Soviet spy exchanges occurred over the decades, including the one depicted here between Soviet spy Rudolf Abel and downed U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers, has become, along with Checkpoint Charlie, one of the quintessential images of the era.

Spielberg doesn’t touch down in Berlin until late in the movie, however. He opens in 1957, on the unsuccessful pursuit by FBI agents of the bland-seeming spy Abel (Mark Rylance) through a Brooklyn subway station. Safely back in his apartment, we see Abel properly for the first time from behind with, to his left, his face reflected in a dresser mirror, and, to his right, the self-portrait he is painting. As an image of a spy’s duality and deceptiveness, it’s pretty obvious stuff, until you notice that Spielberg is also quoting Norman Rockwell’s quintessential Eisenhower-era painting, “Triple Self-Portrait,” thus making this spy somehow, from the outset, almost as all-American as his Boy Scout lawyer James Donovan (Tom Hanks).

They meet after Abel is finally arrested at his easel. Donovan, a successful, straight-arrow insurance lawyer who once worked for the Allies at the Nuremberg trials, is appointed pro bono by his law partners to defend Abel, under the civic-minded reasoning that a fair trial in open court for a captured spy will set a fine American example to the Soviets. For Donovan, it’s an act of public service. Everyone expects Abel to get the electric chair, but Donovan reasons to the court that the spy did his job diligently and loyally — even, on his own terms, honestly and scrupulously, just like our spies do, and gets him a 30-year sentence instead. But when Donovan seeks to appeal the sentence, as a conventional lawyer would and should, his partners withdraw their approval, and he must act alone. His wife (played by Amy Ryan, woefully underused here) and children aren’t thrilled about it, and neither are Donovan’s fellow commuters, who scowl at him over their newspapers; nor are the vigilantes who shoot up his house one night after the verdict comes in.

But Donovan and Abel have by now built up a friendly relationship based on honesty and trust. Hanks gives us his usual garden-variety Tom Hanks routine, but Rylance’s Abel is a quietly marvelous creation of small brushstrokes and actorly withholding (a trademark of Rylance), an amiable, lightly eccentric man with a calm, mild Scottish accent (the real Abel, son of Russian exiles, grew up in Scotland, immigrating to Russia in 1920, when he was 17). As Donovan plays chess with Abel in his cell, obtains paints and brushes for him, and works the case, he sees more and more of himself in his client, and more and more to admire, including his quiet steadfastness and his lack of fear in the face of death.

As Abel’s case moves toward appeal, Spielberg slowly introduces Powers (Austin Stowell) into the narrative, as he is recruited out of the Air Force and into the CIA, which needs “drivers” for what they call “the article.” “Drivers” are pilots and the “article” is the top-secret high-altitude spy plane, the U-2, headquartered in Peshawar, Pakistan, and able to reach 70,000 feet over Russia. We’ve already seen their spy; these are ours. And the linkages Spielberg makes are repeated and specific. One shot of the U-2 pilot instructor ends with the words, “Here’s what you’ll need on every flight,” and as he is about to display it, we cut instead straight back from Pakistan to Brooklyn and an array of Abel’s evidence being examined by NYPD detectives — mirror image, we are them and they are us, two can play at that game, over and over again throughout the movie. Abel and Powers are twinned via two coins, Abel’s “hollow nickel” at the beginning, containing a microdot document, and Powers’ “suicide dollar,” concealing a needle laced with lethal shellfish toxin. If captured, he is himself a highly prized item of classified information and has orders to “spend the dollar.”

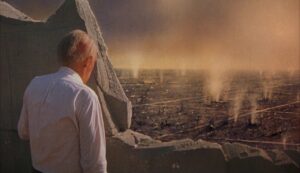

Powers’ failure to make said expenditure is what brings us finally to Berlin and the Glienicke Bridge. The movie bypasses entirely the huge international uproar prompted by the Soviet capture of Powers and the plane’s wreckage — Khrushchev canceled a long-planned summit in Paris and rescinded an invitation for Eisenhower to visit Moscow — but Spielberg doesn’t stint on the crash itself. After being hit by a ground-to-air missile, Powers faces the nightmare ordeal of ejecting from his cockpit without first having disconnected his oxygen tube, and is dragged downward for miles — outside the fuselage — until he can disconnect and open his chute, a vertiginous, nerve-shredding sequence that exemplifies the best of Spielberg.Unlike Abel, Powers gets no fair trial, his lawyer is a hack appointed to speed a conviction, and the guilty verdict — 10 years’ hard labor — is greeted by thunderous applause from the gathered multitude of apparatchiks and Communist Party robots. After two years, however, feelers are put out about a spy swap for Abel. Donovan, still Abel’s lawyer, is reluctantly commissioned by the CIA to negotiate, unofficially and deniably, with the Soviets and East Germans (“who may not have the same agenda …”) to bring Powers back home.

Here the movie enters territory familiar to us from 1960s spy movies like, most obviously, “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold,” with its famous opening and closing scenes at Checkpoint Charlie and the wall (the latter is referenced briefly here), but also “Funeral in Berlin,” the second Michael Caine/Harry Palmer movie, from Len Deighton’s novel, in which spies travel back and forth across the Berlin Wall in coffins, and Michael Anderson’s “The Quiller Memorandum,” about a neo-Nazi revival in West Berlin. It’s John Le Carre times Charles McCarry, a wilderness of mirrors, the looking-glass war.

Spielberg’s Berlin has the same cheerless blue-gray color scheme as his stateside jail scenes, and the spirits of Kafka and Koestler hover over Donovan’s efforts to make the necessary contacts among the Soviet and East German authorities to discuss an Abel-Powers deal. Set against the bustling prosperity of West Berlin — where moviegoers can catch Stanley Kubrick’s “Spartakus” and Billy Wilder’s Berlin-set Cold War farce “Eins, Zwei, Drei …” — the East is still a bombed-out ruin, beset by feral teenage street gangs and lines for everything, and ruled by devious Party bosses and manipulative police chiefs. (The Coen brothers’ glaze on Matt Charman’s original script is most noticeable in the Berlin section — one character, with the quintessentially Coen-ish name of Ott, could be straight out of “Barton Fink.”)

As a retro-Cold War thriller, “Bridge of Spies” is an efficient, exciting entertainment dotted with nicely executed set pieces — the U-2 crash, the subway pursuit, the final swap and others — but it’s also a Spielberg movie, which usually means trouble somewhere. With his movies one must always ask: Where is that one calamitous lapse in artistic judgment we are so used to wincing our way through in his movies? In “Munich,” it was the fantastically ill-conceived final montage of Eric Bana’s Avner having his sex life invaded by flashbacks to the killings in the Olympic Village. In “Lincoln,” it was the black soldier reciting the Gettysburg Address. In “Schindler’s List,” it was the girl in the red coat — possibly the whole movie, even. There’s always something.

In “Bridge of Spies,” there’s no single wrongheaded or boneheaded sequence; the irritations, which are minor, are more diffusely woven into the fabric of the movie. The innumerable links between us and them — “We both do it; we’re no different, no better” — seem redundant once, during Powers’ torture ordeal, we see that the Russians are, according to the evidence the movie itself provides, obviously a lot worse than us. Perhaps the nearest Spielberg comes to a large-scale lapse is when he deliberately twins two moments seen from trains: one of wall-jumpers getting shot down in Berlin, and the other, framed exactly the same way, of happy children fooling around on a backyard fence, seen from the Brooklyn El. Apparently we’re not exactly alike after all, but Spielberg wants to have his cake and eat it too, as he often does.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.