Greg Campbell: Bearing Witness to the Hell of War (Audio and Transcript)

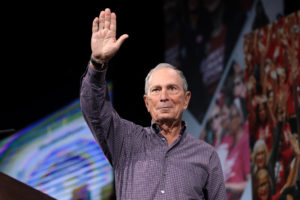

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer and journalist Greg Campbell discuss Campbell's documentary about the late photojournalist Chris Hondros. Journalist and filmmaker Greg Campbell. (Nicole Tung)

Journalist and filmmaker Greg Campbell. (Nicole Tung)

Listen to the interview in the player above and see the full transcript below. Find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Posted by Eric Ortiz

RS: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where hopefully the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, it’s Greg Campbell, a writer, a journalist, and now a film director, at least in the last four, five years. He’s been making a film about his childhood friend who went on to become an internationally known news photographer in Kosovo, in Iraq, Afghanistan, and finally died in covering the war in Libya. And that was in 2011. Hondros is the name of the film, and it reminded me so much of why I–the negative side for me as well as, of course, the positive in learning, but the scary side. I didn’t have extensive coverage of war, but I remember the first time I went to Vietnam and, you know, found myself in the middle of a firefight, and actually lost control of some of my bodily functions. And people told me, soldiers and journalists who were out there, you know, that was sort of normal. I mean, it gets really crazy and scary. And of course in the film Hondros, about Chris Hondros, he ends up giving his life, as many journalists have done. But the photojournalists are a particular breed, and your film captures that around this very significant photographer. The courage–you have a compelling scene at the beginning of the movie, or very early on, where he gets his, probably his most famous photograph of someone on a bridge in Liberia. And it becomes world known; what does that, what does it show? Is it the–it’s a young soldier, it’s a rebel; is he scared, is he empowered? And that sort of put Chris Hondros on the map as one of the great combat photographers, is that not the case?

GC: Yeah, that’s exactly right. Chris had been working in difficult regions in Africa and the Middle East prior to that photograph becoming so popular. And it was that that really sort of put him on the map and brought him to the attention, to the upper stratospheres of his profession, where he always sought to be. I was in close touch with him when he was covering that conflict in the summer of 2003 in Liberia, and it was an extremely dangerous situation. Because the capital city was surrounded by rebel soldiers, and those rebel soldiers were getting closer and closer, and the noose was tightening around the city center, which of course was filled with civilians. And they were being targeted with indiscriminate fire from mortars and from, of course, small arms fire. And it was extremely dangerous, because Chris and the other photographers who chose to stick it out in that environment were, of course, susceptible to death or injury, just as the people that they were covering. And I spoke to Chris on the phone when he was weighing the option of perhaps evacuating, taking up the invitation by the U.S. Marines at the nearby embassy to evacuate any journalists who wanted to leave. And he said there were two things going sort of through his mind, and one was that he didn’t feel that it was fair to leave the people behind who couldn’t stay without somebody witnessing what they were going through. And the second was sort of a decision that he made, that he’d spent so much time and energy arriving to this place to do this work that he felt was important to do, that it just, he didn’t feel like it was being true to his own goals to evacuate when it really became hairy and really harrowing. So this image that you’re talking about was on the very middle of a hotly contested bridge, and the encroaching forces were on the far side of the bridge, and Chris was with the government forces on his side. And he had an epiphany that if he was going to cover this war the way that he felt it needed to be covered, he needed to be right in the midst of it. So when the soldiers charged the bridge and launched an attack on the opposing forces on the other side, he was right there with them, and vulnerable to the incoming fire. And he took a photograph, which you’ll see in the film is stunning in its sort of duplicity; it shows you the violence and the chaos, of course, of that particular moment, but it also shows one of the paradoxical things about being in a war, which is the exhilaration that can come from it.

RS: But you also see fear in his face, and you can interpret that shot, that photo, any which way you want. I mean, either it’s a terrified young man or it’s an exuberant young man, and maybe all those emotions are in there, in the thrill of battle and the fear of battle. But let me say something about your film and you, first of all, by way of introduction. This is your only film; I mean, you’ve done some other shorts and so forth, but you’re basically a print person; you’ve edited the Boulder magazine, and so forth. And you guys met in, what, a freshman high school English class. And you were making sort of a home video movie, and were sort of play at war, right?

GC: Yeah.

RS: Yeah, playing at war. And what I liked about the film, I have some criticisms that I’ll get to, but what I very much liked about the film is we see a guy who really is quite exceptional, Chris Hondros. And he learns–I mean, it’s not the kid playing war games–the power of his photography, and the important thing of his witness; he witnesses the carnage, the suffering. Just to mention another one of his iconic photographs, maybe the best one that’s in the film, one of the most powerful, is when a car of civilians is shot up by Americans in Iraq, and they were not a threat to anybody. And suddenly there’s this young woman and her parents are dead, have been shot in the car. And then what I thought was very powerful in your film is you didn’t leave it there; you found that young woman later, you interviewed her. And she was–you know, no, she wasn’t forgiving, and she didn’t understand why this happened; she was angry. And she thought the Americans were monsters for killing her family. And this was years later, and she’s obviously a very thoughtful person, but she wasn’t going to say, oh, “stuff happens in war,” or “collateral damage”–no. No, she said, you folks are the devil, the Americans, and you visited the carnage of the devil upon us in Iraq, and I’m not going to forgive, and you killed my family. That was very powerful in the film. You went and found the woman that was the subject of what is probably his most famous photo, isn’t it?

GC: Yeah, I would agree with that, I think that’s definitely his most famous photograph, and it’s certainly the one that I think resonated the most from his extensive coverage of the war in Iraq, the one that really reached the American public. And we didn’t know what she was going to say when we interviewed her, and in fact we figured there was probably an even chance that she would not want to be interviewed at all. And we approached her at a difficult time in Iraq’s history, the summer of 2014, which was when ISIS had first come on the world stage and seized control of Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul, which is where she lived. And we weren’t sure if she was within the city limits still, or if she was alive, or where she may have been, if she had fled. So my crew and I took about three weeks on the ground in Iraq to finally locate her. And you know, as you saw and commented upon, we gave her the opportunity to speak if she wanted it, and she had quite a bit to say.

RS: That scene is worth the price of admission, I mean, worth your movie; that one interview you have, for my money, is where you capture the real horror of war, particularly a war that is very difficult to justify.

GC: Yeah.

RS: I mean, the movie does not examine whether any of these wars are needed or not, but the subtext really is that this is unnecessary violence. I mean, in every instance you describe, you really don’t offer a plausible explanation of why we’re there, or why there’s a civil war, or why one part of a community is killing another part. And you know, I think if the movie, it didn’t set out to do it, but I think the movie begs the question of, did any of this have to happen. And your interview with that woman, young, now she’s older, she was what, about four or something when her family was killed right before her eyes.

GC: Yeah, she was five years old.

RS: Five years old. And the American sergeant who orders the firing and so forth, he’s really contrite later in life; you have an interview with him and so forth. Very much liked the scene, by the way, that Chelsea Manning revealed and got her sent to jail, of shooting up a car, that had Reuters photographers and other civilians there in Iraq. And I must say, in that scene, the question that she raises is, it’s not just you make mistakes, you Americans; it’s not just that you came here and messed us up; she is suggesting that we are actually evil in our indifference, our contempt, our use of violence. And you know the fact is, we are responsible for about half of the weapons in the world; we have been the, and Martin Luther King pointed out just shortly before he died, around Vietnam, “We are the major purveyor of violence in the world today,” he said. And you know, a lot of this carnage that you describe in your film is something that we bear a significant, if not always major, responsibility for. And so what your, that woman–I mean, it just got me, that scene.

GC: Yeah.

RS: Where she just lays it out. You know? Who are you–and I’ll never forget the words, do you remember the exact words she–she uses something like “evil” or “monster”–

GC: Oh, yeah. She said if the person offering the apology was in front of her, she would want to drink their blood. And that even if they had drunk every drop, she still wouldn’t be satisfied.

RS: That is an incredible–I mean, what did you think when she said it? Because she’s such an appealing person, you know, as a–

GC: She’s very strong, yeah–

RS: And the–sorry, just for people who haven’t seen the movie, and they should see the movie–when her parents are killed before her eyes, you know, she’s just this pathetic child, and you feel for her. But she comes back in your film as, you know, a full-grown woman with ideas and anger. And it’s not that she’s a crazy person; she’s laying it out the way she sees it. And yeah, that scene, when she says even if I drank the blood of the people–and we meet one of the people who did it, right, in your film.

GC: Yes.

RS: You know, so set that stage, because I do think it’s really incredibly powerful.

GC: I appreciate that. And it is powerful, and I think that there’s a lot to unpack from that. And I think the place to start would be, you know, Chris’s role as he saw it was to be in these places when things like this happened. So that he could convey back to the public in the United States what was happening in their name. And that was information that he thought was important for people to have, so that when the time came to fulfill our obligations to democracy and vote and look clearly in the eyes of what the decisions that we make, at not just the policy levels but in the ballot box, what they look like on the ground and the effects that they have. One of the most moving quotes that he said about that situation was that when people say that war is hell, this is what they’re talking about. They’re not just talking about battlefield stuff and the tanks on one side of a battlefield versus tanks on another; we’re talking about the civilian toll. The casualties that happen far from the eyes of people who voted for the politicians who are implementing these policies and making these decisions to send our troops into harm’s way. And therefore putting civilians in harm’s way. And one of the greatest reactions I had to that scene was from an experienced conflict photographer who we feature in the film, Mike Kamber, who spent many, many years in Iraq. And his opinion about that scene was that it just really typified what was happening in Iraq: the chaos that you’re putting the soldiers into in this impossible situation where they’re fighting in urban environments against an enemy that doesn’t necessarily raise a flag or wear a uniform, in the midst of a civilian population with arbitrary rules of engagement in extremely hostile situations. And of course, things like this are going to occur. And while there had been reports of civilian casualties, and reports of rules of engagement going awry, this was the first occasion when it was brought out with photographic proof. I mean, you can’t get much more raw than seeing a little girl, anguished in ways that we can’t even imagine, covered in blood from her mom and dad who were just shot to death in front of her eyes. And those images brought home immediately the stories and the effects of our foreign policy on the civilians of this country we were occupying. And that’s what Chris’s role [was]. So even though there’s not, as you said, perhaps a solution or a question raised as to why we were in these places, the role that Chris had was to inform people about the consequences of decisions that were made at sort of the top policy level. And because it was so powerful, because this series of images led to such outrage and conversations about what we’re doing in Iraq at that time, Chris was interviewed very extensively. He spoke about his experiences and his opinions about this particular event; he and I spoke to this soldier that you mentioned, extensively, once in 2009 and once again for this film. And the only person that we hadn’t heard from, who was alive and capable of commenting about this, was the person at the center of it all, who had become an icon of civilian suffering. Not just in the Iraqi war, in my opinion, but in many wars, any war. And so I felt an obligation to find her and ask if she wanted the opportunity to comment about this life-changing event that she had endured. And she did; she was eager to sit down and speak with us, and as I said, I didn’t know what she was going to say. I think in my heart, you know, in the back of my mind, I was taken aback when she made those comments. And it feels a little foolish now to think that I would be startled, because clearly, what else was she going to say.

RS: [omission for station break] I’m right back with Greg Campbell, who has made a really interesting documentary about the photojournalist Chris Hondros; it’s called Hondros. He had to be on the bridge, he had to be there when the girl was shot; and he died, he died because he was in Libya and when, you know, a truck got exploded, a car got exploded and he died. And he felt if he’s not there, there is no witness. And that is the interesting contradiction now of American policy abroad; we can intervene with drones and everything else without even putting a single soldier in harm’s way, and the American public doesn’t really care very much. And yet, there are people at a wedding where that drone hits, or where our bombs hit or anywhere else, that are going to be killed, and their families killed. And this young woman, that scene, for my mind, it’s not only the high point of your film, it’s one of the great photojournalisms that you pulled off.

GC: Thank you.

RS: So just set that stage a little bit more. She provided a whole context. You began with the question, or–just tell us.

GC: Sure thing. Let me back you up one second just to correct one factual thing, is that when Chris was killed in Libya, he was killed in a mortar attack, it wasn’t a–

RS: Oh, I’m sorry.

GC: That’s OK, I just wanted to point that out, it wasn’t a car bomb. So when we visited Samar Hassan in the place that she was taking refuge from the ISIS occupation of her hometown in Mosul, you know, mainly I wanted to just hear her recount the story and tell us what she remembered about the night and how it affected her. And clearly, that it did affect her is sort of, that was a foregone conclusion. And you know what we found was a woman who, young woman who is headstrong; she seemed to be very independent, but at the same time was, admitted to having psychological troubles because of her–untreated psychological troubles because of the things that she experienced, this event. And the event, I’ll just lay that out, was in the city of Tal Afar in northwestern Iraq. She and her family, I think she had five brothers and sisters including herself, were in the backseat of the family Volkswagen. And mom and dad were in the front seat of the car. And there was a curfew in this town set by the U.S. military. And to hear Chris explain it, the curfew wasn’t, you know, strenuously enforced; it was more of a suggestion, get off the streets by the time the sun’s down. And these folks were coming back from a health clinic. The mother had some stomach pains or an upset stomach, and the father was going to take her to see the local doctor, and all the kids insisted on coming with them. And so they all piled into the car, and they were late leaving the doctor’s to return home. So as they were doing so, in the empty streets, they were the only car out and about, and the sun was just at dusk, and so it was very difficult to see. The lights were on in the car, they were approaching an intersection. And then we switch to the perspective of the soldiers, who see what they believe to be a suicide bomber coming their way, because they’d come under grievous attack in that particular town; it was hotly contested at that point in time, and the insurgents that they were combating were perfecting the ability to drive up with a car packed full of explosives and detonate it right in front of the Americans. And so that’s what they assumed was going to happen. And Chris told me that he, too, assumed that that was going to happen. And they therefore opened fire on the car after firing a couple of warning shots. And then when you, you know, look at the perspective again from inside the car, it’s difficult to see anything; you know, the soldiers aren’t holding their lights, they’re obviously blending into the environment because they’re on a combat patrol in the middle of the night, using night vision gear. And so the people can’t see them in the car. And when they hear shooting, the instinct naturally is to drive faster and get away from wherever the shooting is taking place. So that could have been what was going through the father’s mind when he accelerated the car, and he didn’t realize he was accelerating towards the soldiers. And you know, it was just a tragic mistake, and it’s the kind of thing that happens in war.

RS: None of this had to happen. We decided–we, we American voters, the people we elected, and speak for us and so forth–that we were going to reorder Iraq, OK? We didn’t like their dictator. And the fact is, the excuse was 9/11; in your film you talk about how Chris Hondros, after 9/11 he was just off to the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq, and that just fundamentally changed his life, and he sort of became a full-time photojournalist of war, combat. But the fact is, you know, the excuse for going into Iraq was the World Trade Center–well, there was no connection; Iraq was one of the places in the world where Al-Qaeda had the most difficult time penetrating, right? And the area where this young woman’s family got killed, there was no ISIS; ISIS is an outgrowth of the destruction of the Baath party, and the Sunni representation, and the Shiite militia coming to power and so forth. And so none of this had to happen. This was something we engineered; we have to take ownership. And again, if I have any, you know, hesitation about my enthusiasm for the film, which is certainly a really significant work. But you know, what you’re basically saying is it comes out, the message comes out subtly, and that Chris Hondros understood that. That this, you know, these wars–whether they’re tribally inspired or they’re inspired by empire, and America has the biggest empire the world has ever seen now, in terms of military power–that’s what causes the chaos. It doesn’t just happen. I mean, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but I think her anger–she was saying no, this was not an accident, and I’m not forgiving it. And by the way, the American in your film, the American sergeant that you interviewed, he’s a troubled person, and he didn’t think it had to happen. So why don’t you give us both sides of the coin, ‘cause that’s really what your film is all about. It’s about, you know, the collateral damage that is documented.

GC: I think it’s important, too, to just understand that the film is also from Chris Hondros’s perspective, and why he felt it was important to be in the places that he went, and why he put himself in these dangerous environments that easily could have resulted in his injury, and ultimately did result in his death. Because it’s for the very reasons that you’re bringing up, which is, when you say “none of this needed to happen,” and that the war was built on lies–there’s no disagreement with your analysis. And at the ground level, what’s needed in order to make our voters and the people who decide who’s going to be in positions in government, representing us with their strokes of the pen, the very first cog in the machinery is the photojournalist, the people on the ground level who are there to be able to have access to the soldiers who are fighting in our name, to have, to brave going behind the enemy lines, to look at the evidence of collateral damage when the Pentagon claims that it has pinpoint precision and never kills a civilian by accident. To be able to have those people who are on the ground, watching these things. And I think the instinct is to demonize the people who are in immediate proximity to a moment, whether it’s the person behind the wheel of the car, if we’re talking about this particular situation, who ignored a warning, you know, from the soldiers who fired warning shots over the top of the car, and accelerated foolishly with his whole family in the car, he must have known he was risking their lives, what’s wrong with him; that’s one perspective. You could also say that the soldiers were trigger-happy and should have given the benefit of the doubt to the driver who was approaching them. But neither one of those holds up when you look at the tragedy of the individual situation, and I think Chris saw his responsibility as not to necessarily track backwards in time and assign retroactive blame for how we got into the positions that we were in, but rather to examine what was actually unfolding as a result of decisions taken in the past, so that they could be changed or at least better informed once the opportunity to decide about something like that in the future came again.

RS: The film, really its strong, strong message, is you have to put yourself in the shoes of the people that are getting killed. And the civilians that are getting killed. And that’s what he basically does there.

GC: Yeah.

RS: And I must say, to your credit, and we haven’t talked at all about how you made this film, the crowdsourcing and Jamie Lee Curtis and other people in Hollywood who helped get it out–I mean, we should talk a little bit about that. But I want to praise your skill here, because you’re, as I say, you’re a print journalist and an editor and so forth; you chose that trajectory. And you put yourself in harm’s way to make this film; it was obviously a labor of love. And you learned the trade; I mean it’s, you know, you’re the director, and it is a, you know, I’m not an expert on films, but it seems to me an incredibly effective job. And so just talk a little bit about that.

GC: Well, first of all, thank you for the wonderful compliments; I appreciate them very much. When I was first contemplating the idea of doing a tribute to Chris’s life and examining his legacy, both with the camera and without, you know, being a print journalist my first instinct was perhaps I should write a book and do a biography. But clearly, Chris’s visual artistry just demanded a film; there was just no other way to be able to discuss or present his work without being able to see it. So it became clear pretty quickly that the movie was the route to go. And yeah, I’ll be the first to admit that I knew very, very little blundering into this industry, and there was a lot of trial by fire, a lot of trial and error. And I was pretty fortunate to have attracted some skilled people who had knowledge and experience in this industry from the beginning. And you mentioned Jamie Lee Curtis; there was a real turning point for our film, and it actually involved the young lady we’ve been discussing. We were trying to track her down, as I mentioned; there was a lot of turmoil going on suddenly and unexpectedly in Iraq, and we’d lost touch with her and her family. And we called one of my teammates, a producer of mine, called The New York Times bureau in Baghdad and asked if they had any idea where she might be located. They had done a story on her, a brief piece in the wake of Chris’s death, and interviewed her about where, you know, how her life had turned out. And they said that they lost touch as well, and they weren’t sure how to reach her, but suggested that maybe we try Jamie Lee Curtis. And I think we all thought we were hearing him incorrectly, and we said Jamie–who’s that guy, you know? And it turned out, no, we’re talking about Jamie Lee Curtis, the Hollywood royalty Jamie Lee Curtis, the one you’re thinking of. And apparently she had been so moved by Chris’s photographs from Tal Afar, and so touched by the tragedy that befell this family, that she did the same thing that we had done and reached out to the same person at The New York Times to see if she could help or assist in any way, if there was a fund set up for her, or whatever may be the case. And there’s not and there wasn’t, and so she just left her contact information if she could ever be of any assistance. And I emailed her right away, and she emailed right back, and she was a staunch supporter of our film, and an amateur photographer herself. And it was just, it was a real perfect sort of partnership. And she brought along her godson, another well-known person in Hollywood, Jake Gyllenhaal. And Jake had just started a production company, and immediately when he saw some of our early scenes he could see pretty quickly that Chris Hondros, there was something special about him and about the work that he did, and he wanted to get on board with it as well.

RS: You know, we’re going to wrap this up soon, but I’m always looking for role models. I teach at the University of Southern California in the Annenberg School, and what you did here is really, you provide a, not only, obviously we can’t all be Chris Hondros and we can’t all take those risks and danger, and I’m not saying–and you did take some risks to make this movie. But the fact is, you used the Internet in a very positive way. You didn’t have to go to some big-money people at first; you didn’t have to get, you know, big authorization, you know. You did crowdsourcing, and you raised some, what, 80, $90,000 fairly quickly.

GC: Yeah.

RS: I looked at the original pitch and everything, a pretty convincing pitch. And that’s kind of a model for responsible journalism. Everybody’s bemoaning now, you know, what’s going to happen to journalism–well, you did very good journalism, excellent journalism here yourself. And you did it by saying, OK, I’m going to make this movie; I don’t know how to make a movie, I don’t even, and I don’t have the money. And so just, let’s end on a positive note here that people can make choices about doing significant work, journalism, and they don’t always have to sell out, which is unfortunately what a lot of we hear about.

GC: Well, I think it’s a great note to end on, because the people who supported our kickstarter campaign don’t get nearly as much love and recognition as they deserve. Because you know, we were trying to raise a mere $30,000 to afford to buy a camera and maybe do a test interview to see if it was even worthwhile. And we raised that amount of money within four days of our 30-day campaign online. And the donations came from all around the world, in like literally every corner. Some people gave a dollar, some people gave $10,000. And to see the sort of outpouring that was purely motivated by their love and admiration of Chris Hondros, it just really convinced me that we were on the right path to make a film about his life. I clearly was convinced of that from the beginning, but this was just really positive reinforcement, and I owe everybody who donated and supported our campaign a real debt of gratitude.

RS: And we owe you a debt of gratitude for keeping the memory and the example of Chris Hondros alive. He was a Pulitzer Prize finalist several times; he, really incredible, iconic photographs. That’s going to wrap it up for this week. But thanks for joining us on this edition of Scheer Intelligence. And we’ll be back next week, but I can’t leave without thanking our producers, Rebecca Mooney and Joshua Scheer; our excellent engineers, Mario Diaz and Kat Yore, here at KCRW. And see you all next week.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.