Art Has Lost Its Meaning

Whether it is pretentious conceptual academic art, or vapid expressions of serenity that serve only to fulfill your apartment's feng shui, Robert Shetterly says that most art today has been tainted by unfettered capitalism, which values consumer interests over truth. Whether it is conceptual academic art or vapid expressions of serenity that fulfill your apartment's feng shui, Robert Shetterly says that most art today has been tainted by unfettered capitalism.

By Thomas Hedges, Center for Study of Responsive Law

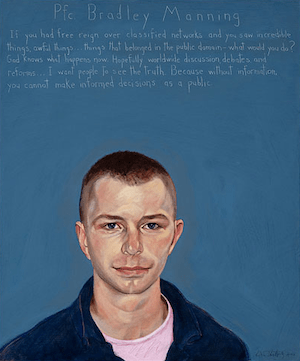

Robert Shetterly, 66, is a painter who travels to schools, museums and sandwich shops across the country with an exhibit he has been working on for more than 10 years called “Americans Who Tell the Truth.” The portraits feature such activists as James Baldwin, Bradley Manning and Chief Joseph Hinmton Yalektit. These are people, Shetterly says, who have preserved democracy and exposed lies.

Shetterly’s paintings defy contemporary art, which is steeped in commercialization. He dislikes abstract works that fail to express anything real. That sort of art, he says, is about comfort. It is about happiness and distraction. Whether it is pretentious conceptual academic art, or vapid expressions of serenity that serve only to fulfill your apartment’s feng shui, Shetterly says that most art today has been tainted by unfettered capitalism, which values consumer interests over truth.

“Artists today,” Shetterly says from his home on Deer Isle, Maine, “are using the dominant culture system to determine how they value themselves and I think that’s a very dangerous thing for artists. … Art is one of the few places where critical voices can live. Even in universities these days it can’t live with so much political pressure. The real voice is lost.”

“Art,” he says, “is one of the last places where people can have the freedom to live outside the system, or at least on its scraps, instead of trying to be one with it, which robs you of your voice finally. It’s so easy to be co-opted.

“This system will take anything from anybody and if it can commodify it, it will embrace it.”

Shetterly’s portraits are honest. His subjects are not embellished, distorted or caricatured. Most are smiling. Their clothes are painted simply, almost as if they don’t matter. Behind each face is a soft-colored backdrop, usually a pale green, brown or blue, as opposed to commissioned portraits of nobility, which surround the subject with objects of power and status. There is a quotation written lightly in the forefront of each picture. Every portrait is the same size. The expressions are most striking to the viewer. Some are concerned. Some are generous. Most are a profound mixture.

In the end, Shetterly refuses to present his truth tellers in a supernatural light. They are not flawless, like the celebrities in magazines and on television. They are not detached from regular life. They are people who have chosen to resist.

“In the ’60s, art was everywhere,” Shetterly says. “You could not turn on a radio station anywhere in this country and not hear Odetta; Bob Dylan; Peter, Paul and Mary; Phil Ochs. They were talking about peace, about war, about civil rights and they were raising the level of consciousness.”

“Now,” Shetterly says, “you have to find little community stations that play that kind of music, or small galleries that’ll show that kind of art because it’s not commercial.”

The lifelines that used to preserve art and dissent, he says, are being destroyed by a growing market that cannot make money out of truth. This leaves many artists broken. Some, like Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, survive by adhering to the market’s rules. They replicate society’s obsessions, producing entertainment, pop or absurdist irony.

“But aesthetics are a means to an end,” Shetterly says about the emphasis on image. “When they become the end themselves it becomes tiresomely academic [which does not] invite us to think and feel about something human. Instead it’s about composition, color and brushstroke. Those things are a means to delivering the message. If a painting is only about its own medium, it becomes very narcissistic and ingrown. … It is either academic or about titillation … it’s about flash. It’s about turning our nerves on but not our minds. It’s really about distraction. … It all goes by so quickly and it’s exciting and feels good, but it also takes us away from what is important.”

Shetterly says that people who have a genuine interest in art are often beaten down and stripped of their ability to pursue the truth. The commoditization of art, if it hasn’t already reeled you into its arms, exiles you to the world of academic theory and nonreality, where you do not have the capacity to rebel against the free market. Either you adhere to the rules or you are cast into an irrelevant pool of degree-holding artists who have left the real world in search of vague ideas like space, subjectivism and postmodernist expression.

Samuel Scharf, 29, is an alumnus of American University, where he studied art. In the last decade, he tells me, the university has moved away from traditional instruction and embraced the more contemporary style of installation art.

Installations, which are popular among young artists, are three-dimensional presentations that focus on space in the particular area they occupy. They are mostly temporary and convey elusive ideas that are rooted in theory. The pieces are cleansed of politics, history and morality.

If university art departments haven’t already shrunk, they’ve transitioned from the traditional style of instruction to one that is based in abstraction and historiography.

Scharf has infused his gallery, situated in the growing, gentrified neighborhood of Columbia Heights in Washington, D.C., with the new tenants of contemporary art.

A young woman who works with Scharf tells me that American University, like many other schools, is teaching students how to strategically place themselves within the art movement rather than defy that trend.

“When you have a curriculum that’s focused on critical theory,” she says, “so that you’re reading everything from early 1900s to 1970s theory to 1980s, 1990s — you get this foundational education on where the art world is and why it is where it is and then. … You chose to situate yourself in a certain way.” But when I ask the artists to elaborate on their pieces, they choose not to.

“I never want to speak for the artist,” Scharf says. “I’m an artist, and I don’t ever want anyone to say what I’m thinking about my work.”

“It’s just her work,” he finally says about a woman’s photograph in the gallery.

There is a pervading sentiment that artists ought to fit somewhere into the general arch, which has little room for artists who search for truth. There is no talk of the cokeheads that stand in the street one block away, looking for a fix. Nor is there talk of the gangsters who pull up in their sports cars and sell them the drugs they crave. There is no talk of power, even though the White House, Capitol Hill and K Street — where the lobbying firms are located — sit fewer than four miles away.

“So many people today know that there’s a lot wrong but it’s not being articulated for them so that they can act on it,” Shetterly says about artists like Scharf. “Art should do that. It gives you the permission to act. But it’s been removed on purpose because it has an effect on the consciousness of people. It verifies what they sense is wrong, but cannot articulate for themselves.”

Centuries ago, the power elite controlled art through propaganda. Artists were paid to enshrine the aristocracy.

“[Francisco] Goya, before he became the Goya most people think of,” Shetterly says, “was a court painter. He was there to reinforce the caste system and the system of royalty.

“A person who painted a portrait for a king,” Shetterly says, “was painting what the client wanted to see. A person who’s painting for the rewards of an economic system is painting, similarly, for what the client wants to see.”

The difference between then and now, Shetterly says, is that art today is not about superiority and propaganda, as with royal portraits, but about turning our brains off. It is about silencing pain and suffering, and distracting ourselves with images that bring short-term pleasure, surprise and satisfaction.

Mainstream culture, Shetterly says, keeps us distracted from the fact that our luxury, for example, comes at the expense of cotton farmers in India, garment makers in Bangladesh and Hispanic tomato pickers in Florida. The goods we buy at retail stores and supermarkets are cheap because the labor used to cultivate those products is underpaid.

“Our culture has been taking a lot of warmth and comfort from the rest of the world in a very exploitative way,” Shetterly says, “so that we can live that way while other people don’t.”

When art ignores truth, it mirrors a society that is unaware of its surroundings. Art as happiness is a defense mechanism. It reinforces our desire to live in a vacuum that is free of anguish and responsibility.

“The market encourages artists to find and capitalize on gimmicks,” Shetterly says. “It’s the argument of Coke, of Exxon Mobil.”

Art today is about protecting the consumer. It is no longer propaganda for those in power, as art has been for most of history. It is about reassuring customers that there is nothing wrong, as long as they continue to shop.

This article was made possible by the Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.