Arm America? John Wayne Would Lose Real Shootouts

Some of the ideas to solve gun violence are right out of Hollywood—because in reality, more "good guys with guns" only increase the odds of tragedy. John Wayne and Marsha Hunt in the 1937 movie "Born to the West." (PxHere)

John Wayne and Marsha Hunt in the 1937 movie "Born to the West." (PxHere)

When Pat Buchanan kicked off his presidential run in the 1996 Republican primary, he posed wearing a gun belt in Tombstone, Ariz., at the entrance to the O.K. Corral. “I wanted to wear a gunfighter’s outfit,” Buchanan told reporters. “So I did it.”

If Buchanan had been wearing that gun on the streets of Tombstone in 1881, he’d have been lucky not to run into Virgil or Wyatt Earp, who would have clubbed him over the head (“buffaloed” in the parlance of the time), hauled him off to jail and fined him $25 for carrying a firearm within the city limits.

Like many frontier peace officers, the Earps didn’t debate gun control, they enforced it. Many officers in the Old West who did not control firearms on town streets came to regret it. In 1871, Wild Bill Hickok, town marshal of Abilene, Kan., responded to pistol shots in the dark by not only killing the shooter but then wheeling and firing at a man approaching him from behind. Wild Bill accidentally killed his friend Mike Williams, who was rushing to Hickok’s aid.

In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his famous thesis, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Turner argued that the frontier, “the meeting point between savagery and civilization,” was the defining element of the American character. With some qualifications, most modern historians still pretty much agree with him. The problem is that our image of the Old West has been distorted through the lens of Hollywood.

Except for soldiers and lawmen in the Western states and territories after the Civil War, there wasn’t much of a need for most Westerners to stock up on guns, at least as the threat of organized resistance by Native American tribes waned toward the end of the 1870s. Farmers and ranchers, of course, needed guns for hunting. For many, the single-shot, muzzle-loading rifle muskets they brought back from the war were sufficient.

In Western movies, every pioneer, cowboy and saddle tramp carries a Colt, single-action, “Army,” six-shot revolver and, usually, a Winchester repeating rifle. Both guns appeared on the market around 1873. The cost of those guns back in the day varies, according to which source one consults. The Cody Museum in Wyoming puts the average cost at about $18 for either weapon, which would be around $350 in today’s dollars. The problem for people who lived on the frontier in the 1870s is that few had that kind of money. To put that in perspective, it might take a working cowhand a month’s wages to buy a Colt or a Winchester.

A Glock 9 mm semi-automatic can be purchased today for around $475, but a lot of people today have much more disposable income than Americans on the frontier 140 years ago did. Stated another way, it’s very likely that there are far more guns per capita in the West (and South) now than there were in the days of Hickok and Earp.

In fact, even Western peace officers didn’t always carry guns when they weren’t working. When Tombstone town marshal Fred White was accidentally shot by the notorious Curly Bill Brocius, Wyatt Earp had to borrow a gun before running out in the street to help him.

The Old West had far less violence than what the big and small screens would have us believe, the reason being that there were far fewer guns than we see in the movies. But precisely because officers had to deal directly with men who carried guns, the job of law officer was dirty and dangerous. It was a hazardous profession, even for those who had experience with guns. Two of Wyatt Earp’s brothers were shot, one fatally, and many of the lawmen he knew and worked with took a bullet at one time or another (including Bat Masterson’s younger brother Ed, killed by a drunken cowhand in Dodge City, Kan.).

Many marshals and sheriffs sensibly designated their streets as “no-carry” zones, and the overwhelming number of townspeople approved. Now, in the wake of the Parkland, Fla., high school shooting, President Trump wants to transform hundreds of thousands of teachers into armed guards—or perhaps armed guards into teachers. It isn’t clear which.

What also isn’t clear is who would pay for the hiring and training of these teacher/guards, not to mention the cost of arms and ammunition. (As one teacher at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School told a CNN reporter, “We don’t have the money for basic supplies, let alone guns.”)

The whole idea creates far more questions than it could conceivably answer. Here are just a few:

● What will these teachers be packing? I mean, if somebody enters a school with an automatic weapon, they need to be able to meet the intruder on even terms, right? Does this mean there could gunfights with automatic weapons in schools, with an alarming increase in casualties?

● Will there be teacher/guards in all high schools? Does this include Catholic schools? What about my old high school, St. Mary’s in Perth Amboy, N.J., where most of the teachers were nuns? Nuns with AK-47s?

● Why stop with high schools? Sandy Hook was an elementary school. Don’t we need to protect elementary and middle schools as well? And what about colleges? After all, 33 people died at Virginia Tech.

Jim Jefferies is from Australia, where they stopped mass shootings with strict gun control, and he perfectly understands the pitfalls of arming teachers.

Our second-deadliest shooting was in an Orlando, Fla., nightclub, with 49 innocent victims. Should nightclubs be added to the list of places that need more armed guards? And how about churches and synagogues and mosques after the massacres in Texas and South Carolina?

By the logic proposed by the National Rifle Association and Trump, surely all places and events where large numbers of people gather will need armed guards—sporting events, amusement parks, fairs, victory parades like the one in Philadelphia for the Super Bowl champion Eagles, even presidential inaugurations (though perhaps there weren’t enough people at Trump’s inauguration to warrant more security).

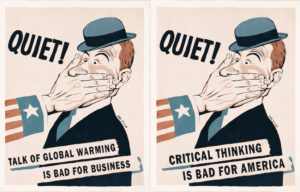

The notion that the only thing that can stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun, famously expressed by NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre, reflects not historical reality, in which the good guys lost about half the time, but Hollywood, where John Wayne never lost a shootout.

Arming teachers pretty much supposes that the teacher is going to shoot faster and better, with more accuracy. It also assumes that the teacher is always going to be the good guy. This week, a history teacher at a Georgia high school barricaded himself in a classroom and fired a handgun before being apprehended. Afterward, a student told reporters that the teacher “disagreed with Trump’s plan to arm teachers.” For once, we have a sentiment from a shooter we can all get behind.

“A gun is a tool,” Alan Ladd says to Jean Arthur in “Shane,” “no better or worse than the man who uses it.” Exactly.

Putting more guns into the hands of more people does nothing to alleviate the problem and does everything to increase the odds for tragedy. I’m a proud owner of several historical guns, and you can have my single-action Colt revolvers and my grandfather’s Russian Mosin-Nagant rifle (probably used against the British during the Irish War for independence) when you pry them from my cold, dead hands.

But then, I don’t have any felony convictions, history of domestic violence or problems with mental illness. I don’t buy guns online or at gun shows and would be happy to submit to background checks and waiting periods. I don’t believe any citizen needs an automatic weapon, and I do believe in the Second Amendment as it is written in the Constitution: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

I also believe in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 16 of the same document, which says, “Congress shall have the power to … provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia.” Emphasis mine.

Most of all, I believe that whatever their flaws, the Earp brothers had a more realistic and intelligent attitude toward guns than do the NRA and our Republican Congress.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.