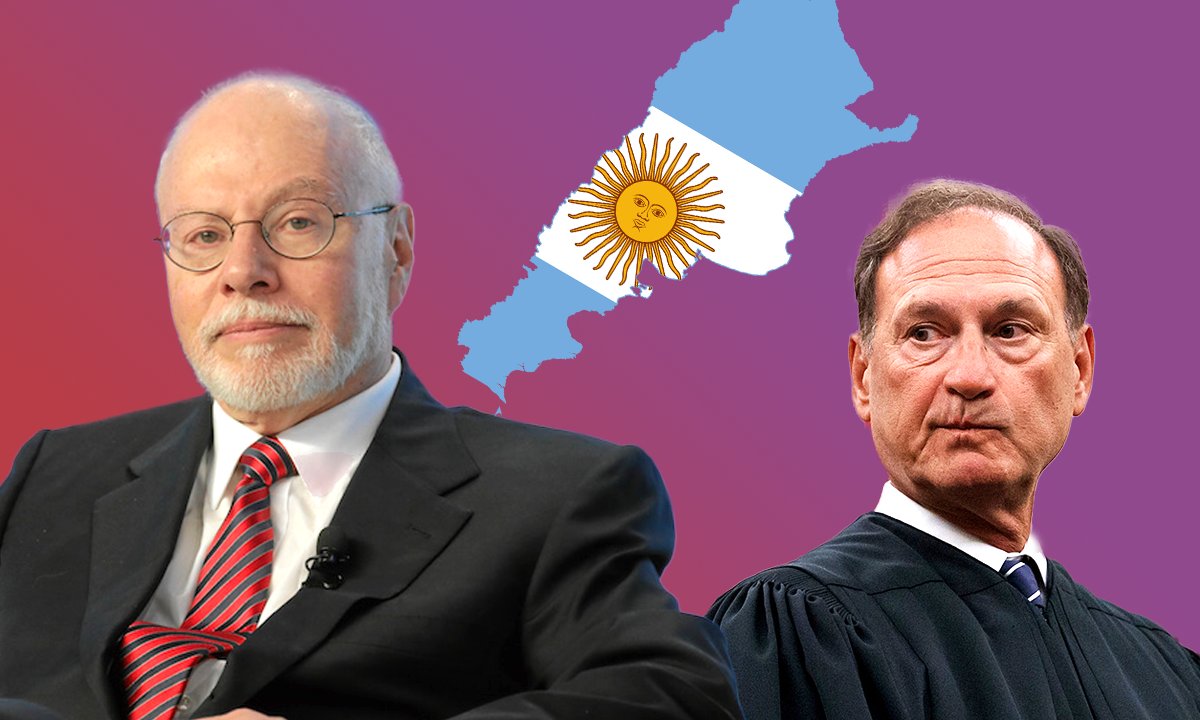

Argentina, the Vulture and the Justice

Paul Singer’s relationship to Samuel Alito illuminates how U.S. law enables vulture funds to deepen immiseration across the Global South. Image: Truthdig

Image: Truthdig

In July of 2008, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito accepted a luxury Alaska fishing vacation paid for by hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer. After ProPublica broke the story in June, Alito airily insisted to The Wall Street Journal that he had done nothing wrong. Many news organizations more or less agreed, treating the story as just another example of high-level but minor corruption, if not a harmless peccadillo. This dismissive response ignored the fact the Alito-Singer relationship arguably affected 43 million innocent victims. That’s the population of Argentina, the once middle-class Latin American nation that has careened through decades of economic crisis and mass unemployment that has at times pushed half the country below the poverty line.

Singer amassed his wealth, estimated at $5.5 billion, in part by running “vulture funds” — investment vehicles that buy bonds from poorer countries at fire sale prices and then hold them for years until they can cash in. The complicated backstory to Argentina’s long saga is laid out in a remarkable book by former Washington Post reporter Paul Blustein, “And the Money Kept Rolling In (and Out) Wall Street, the IMF, and the Bankrupting of Argentina.” Blustein describes how the big investment banks in New York and Europe, with the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), profited by underwriting bond issues worth billions, ignored the red warning indicators when the Argentine economy stumbled and instead, pressured the government to accept even more loans.

After Nestor Kirchner’s newly elected Argentine government said that it could not afford to pay international creditors following the crisis of late 2001, those creditors began to negotiate the country’s bankruptcy. The IMF head, ignoring his agency’s guilt in the debacle, threatened, “At the IMF, we have a problem called Argentina.” President Kirchner answered, “I have a problem called 15 million poor people.” Eventually 93% of the bondholders accepted what in financial parlance is called a “haircut,” settling for 30 cents on the dollar.

Singer amassed his wealth, estimated at $5.5 billion, in part by running “vulture funds” — investment vehicles that buy bonds from poorer countries at fire sale prices and then hold them for years until they can cash in.

Enter Paul Singer. In 2004, he had been part of a successful lobbying push that succeeded in getting the New York state Legislature to modify its laws around “champerty” — an ancient legal principle that prohibits “strangers” to a lawsuit from funding litigation in order to profit from the outcome. Because many global debt agreements are made in New York, the state’s laws govern who can profit from them and how. After the law change, Singer began buying Argentina’s debt at a deep discount in the secondary market. Then he deployed his army of lawyers to pressure the government in Buenos Aires to start paying. His efforts included a (failed) attempt in 2012 to seize an Argentine navy sailing ship docked in Ghana.

Singer’s legal assault hamstrung the country’s recovery for years, and eventually wore the government down. Finally, in 2016, a new president gave him most of what he wanted, turning his original $117 million stake into $2.4 billion — a 1,270% return.

How does the Singer-Alito relationship figure in all of this? For years following Singer’s purchase of the debt, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to take up multiple requests to hear the Argentina case, in effect blocking Singer’s efforts to collect. In 2008, Singer and Alito went fishing together in Alaska. Then, in 2014, the Court decided in favor of Singer’s Elliott Capital, in a decision that Alito did not recuse himself from. The justice defended himself in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, claiming ignorance of Paul Singer’s connection to the Argentina legal case. This defies belief. Anyone who read the financial pages from the mid-2000s onward would have come across regular accounts of Singer’s vulture fund in the Southern Cone.

No one knows why the U.S. Supreme Court reversed itself to hear the case, and in the end the vote for Singer and against Argentina was 7-1. But the fact that Singer had palled around with Alito in Alaska must have encouraged the vulture fund owner to continue his waiting game, rather than accept the reduced Argentinian offers that most other bondholders had long since agreed to. Singer waited 15 years to collect.

The Alito-Singer connection highlights how the international financial and legal system is rigged against the Global South, as yet another international debt crisis menaces the post-pandemic recovery in 54 nations across Latin America and Africa. Mark Malloch-Brown, president of the Open Society Foundations, is already warning, “An Era of Debt Crisis Catastrophe is Dawning.” U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, meanwhile, points out that “3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt interest payments than on education or health. This is more than a systemic risk — it’s a systemic failure. Action will not be easy. But it is essential, and urgent.”

An impressive coalition of activist groups — one of them is called Hedge Clippers — is sounding the alarm and campaigning for simple justice, including bills in the New York state Legislature that would begin to rein in the vulture funds. The coalition, which also includes The Center for Popular Democracy and New York Communities for Change, has published a valuable introduction to vulture funds and the damage they do in the Global South. “New York is uniquely positioned to step in and pass laws that would disrupt the vulture fund playbook and stop them from profiteering at the expense of countries in financial trouble,” their report explains.

The Alito-Singer connection highlights how the international financial and legal system is rigged against the Global South.

Michael Kink, whose group Strong Economy for All is part of the New York coalition, notes that nations once held more power to defend themselves in debt negotiations with creditors. “That changed in the last 25 years,” he says. “Now you’ve got the rise of the vulture funds, which are like pirates. They’ll fund the litigation to bash peoples’ heads until they get what they want. They are totally willing to destroy entire countries to get paid.”

Kink says anti-vulture fund legislation will be re-introduced in the New York Legislature at the start of the 2024 session. Although he is optimistic about its chances of becoming law, the clock is ticking. Francisco Amsler, an Argentinian economist who works with the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., estimates that some $80 billion of his country’s foreign debt is in the form of bonds. “It is early,” he says, “but there’s no doubt that speculative vulture funds are already strategizing around the debt situation of Argentina.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.