Anthony Heilbut on MaryBeth Hamilton’s ‘In Search of the Blues’

What accounts for the strange need of some white scholars -- from the plantation nostalgists of the late 1890s to the "Blues Mafia" of the 1960s -- to honor African-American culture by trying to save black people from themselves?

Who says that taste is only personal and cannot be disputed? The cultural canon is always up for revision, and received wisdom has a shelf life. This is made clear in Marybeth Hamilton’s “In Search of the Blues,” an intriguing study of white scholarly attempts to discover and define the Real Blues. Like the figures in that children’s story, they kept taking a part for the whole, and most often discovered a distorted version of themselves. But they also convinced a lot of people that they were deeper and wiser than anyone else, and that if you disagreed you were a shallow if not a bad person.

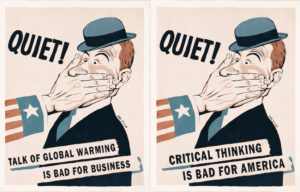

They probably did more good than harm. Although some of the early students were condescending, if not blatantly racist, all of them felt that black music was the most vital element of American culture. This required some arguing at a time when a critic like Gilbert Seldes could patronize “the negroes’ music” as both poignant and mindless — displaying “little evidence of the functioning of their intelligence” — and academics found the culture insufficiently steeped in “folklore,” a term that became increasingly nebulous in the age of mass communication. Yet the stunning detail that connects all of Hamilton’s subjects — from the plantation nostalgists of the late 1890s to the “Blues Mafia” of the 1960s — is that honoring the culture meant saving black people from themselves. The real deal was not now but back then in a mythical past when people were simpler and their expression more true.

This is one of the enduring themes of American culture, both white and African-American. One of the oldest spirituals laments that “the people don’t sing like they used to sing.” The difference lies in the explanation for this decline; gospel singers would say the people weren’t living right, folklorists would say it was the culture that had gone bad. As early as 1845, Frederick Douglass discovered the profoundest meaning in “tones loud, long, and deep. … Every tone [a] testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” Fifteen years before the Civil War, he heard in the sorrow songs a musical code of emancipation. Over a hundred years later, Alan Lomax would write of the wordless moans of the black church, “For me, and I believe, for most southerners, the most magical of all musical sounds is the many-voiced humming of a lining hymn that arises during quiet moments in the black folk service.” Perhaps, indeed, this was the fabled song of the South, the echo of a musical paradise lost, even if that Eden was a product of slavery; as Hamilton notes, there was a masochistic glee in the way outsiders identified with the sorrow songs. But if everyone agreed that the origins were uniquely expressive — and that everything from field hollers to bebop could be traced back to the church sisters’ wordless moans — what happened next was up for interpretation. To use the current jargon, it became a question of conflicting narratives, usually told by outsiders. And always with the implication that they knew better than the actual participants.

A point would be reached when blue-eyed soul singers and white bluesmen would behave as if their own years of hard work and disappointment had made them the artistic peers of their idols. Everyone had a right to claim the blues. Also a right to determine what was “really real,” a church idiom for those whose faith had proved true, rather than ersatz. For blues fans, authenticity became another way of separating the wheat from the tares. Among the discarded items would be most black popular music, particularly the work of female artists. Even if blues fans might share Lomax’s admiration of the sisters on the mourners’ bench, when it came to blues, the word was “Don’t bring me no Bessie Smith,” a musicians’ slang for the great lady’s all-purpose epithet. They didn’t merely disdain the bullshit, they didn’t want the Bessie Smith either. How was it decided that the blues vocalist was ideally male, and the blues instrument ideally a guitar? It was both historically inaccurate and a constriction of harmonic and melodic possibilities, as any gospel singer who has had to choose between singing “by the gee-tar” and “singing by the piano” could tell you.

Demoting the women also meant a constriction of subject matter and emotional resonance. Hamilton dryly observes that “the world … depicted would be pastoral and, with barely a woman in sight, singularly free from the disorganization so evident in the black urban world.” The highly subjective dismissal of women’s voices and themes from the blues pantheon is a rich topic for Hamilton. An American historian now living in London, the author of “When I’m Bad, I’m Better: Mae West, Sex, and American Entertainment,” she is clearly attracted to episodes of sexual transgression, of a sensuous world ignored by the blues scholars whom she frequently exposes as humorless prudes. She had initially prepared to write a biography of Little Richard. That would have been a very appealing topic, at least for me. Little Richard’s acknowledged inspiration, the source of his growls, falsetto whoop, full-tilt personality (and beehive coiffure) was the gospel singer Marion Williams, whose last albums I produced. But instead she was intrigued by the great claims made for country blues singers, e.g., Greil Marcus’ description of a Robert Johnson performance as “a two minute image of doom that has the power to make doom a fact” (and not a moment too soon) or musicologist Robert Palmer’s rhetorical question, “how much history can be transmitted by pressure on a guitar string?” (If there’s a Hall of Shame for such over-listening, many a noted critic would share pride of place.) Precisely because she didn’t share these critics’ enthusiasm — even when praising the work of Johnson or Charlie Patton she doesn’t sound as if she really means it — she was fascinated by the division in sensibilities. So instead of writing about a black gender bender, she wrote about a world in which blacks and women scarcely figure. While there are references to Langston Hughes (who wrote some weak gospel songs) and Sterling Brown (who wrote some great blues), her scholar fans are mostly white and male. Even so, the book’s most dramatic scene involves a diminutive professor of writing, Dorothy Scarborough, trying to photograph a mass baptism, the sole white person in the crowd. And with a couple of brief, disputatious appearances, Zora Neale Hurston almost steals the book. Hamilton is steeped in academic methods and terminology: Walter Benjamin’s endlessly cited “work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction” makes an inevitable appearance. But she also enjoys dramatizing imagined encounters between scholars and their sources, or — more daringly — the eureka moments when some fan plays some record and figures everything out.

Her first group of researchers bemoaned what has happened to “our Negroes” and their culture. They despised all the jazzy trappings of urban life but were not completely hopeless: “There will be the folk blues,” Howard Odom wrote in the late l920s, “as long as there are Negro toilers and adventurers whose naivete has not been worn off by what the white man calls culture.” (This sounds like Norman Mailer’s evocation of the White Negro, or — distressingly — like some hip-hoppers’ dismissal of “white folks’ education.”) By the early 1930s Dorothy Scarborough had introduced a more literary take; her shrewdest observation was that the 12-bar blues resembled an O. Henry story, with the third line subverting what came before. She was both a Southern belle and a member of Greenwich Village’s literary scene; writer Carson McCullers was a student. (McCullers’ nursemaid in “Member of the Wedding” would become an iconic figure in 1940s literature, along with Eudora Welty’s neo-Fats Waller, “Powerhouse”; this suggests that Southern women made particularly judicious use of their folkloric research.) In her fiction and scholarship Scarborough was also infatuated with the spirit world, with ghosts and “haints.” Rural superstitions fascinated her. But, as one friend noted, she was totally baffled upon entering the office of W.C. Handy, the so-called Father of the Blues, and finding it an outpost of Tin Pan Alley.

The only blues researchers to become national figures were John Lomax and his son Alan. In a famous March of Time newsreel, John Lomax, a ne’er-do-well (born on “the upper crust of po’ white trash”) dabbler in folklore, is shown interviewing ex-con Huddie Ledbetter about his good fortune in singing himself out of jail. Nothing about the scene was real; it was staged for the camera with Leadbelly and his friends dressed in striped uniforms. Hamilton laments the “excruciating depiction of Leadbelly as a hapless, hopeless, mindlessly criminal darky, a part that Lomax seems to have set out for him and in which the singer seems to collude.” The initial response was more positive. Leadbelly was a brilliantly talented singer and guitarist, a walking repository of American popular music from blues and reels to hymns and ballroom waltzes. Lomax was convinced that secular tunes were more uniquely black, free of any debt to white spirituals or the white man’s Bible. But they had to be self-contained productions, uncontaminated by popular music or jazz — in other words, hermetically sealed from the worldly influences of radio and, especially, phonograph records. (Like many subsequent critics, Lomax distrusted versatility. His implicit command to Leadbelly was “You’re a colored singer, sing colored.”)

Huddie Ledbetter was visually gripping, an austere, dark-skinned man, who sang and played with a fearful intensity, and drifted with remarkable ease from baritone to high tenor, exhibiting the open-throated tessitura of the best gospel singers. YouTube carries a clip of him singing “Take This Hammer” (to the tune of the white hymn “Where He Leads Me”), his back as straight as his guitar is wide.

Initially Lomax did well by Leadbelly and himself; the two appeared at a Philadelphia meeting of the Modern Language Association where Leadbelly, identified as “a Negro minstrel from Louisiana,” convinced the academics that black music was folklore too. (Alan Lomax shared his father’s respect for the academy’s imprimatur. Many years later he would devise a system, “cantometrics,” that preposterously imagined a kind of Chomskyian structuralism of musical utterances.) Leadbelly was soon a popular star too, mostly in the Greenwich Village folk circuit, black audiences finding his ways too amateur and “country.” Lomax was horrified as his darky became “only an ordinary, low ordinary, Harlem nigger.” The relation ended when Leadbelly came around with the reasonable request, “I wants my money,” and seemed to threaten him with a knife. But their brief union had made both men famous. In the words of Aretha Franklin, who was zooming who?

Besides falling out with Leadbelly, Lomax found himself publicly condemned by Richard Wright, then a committed leftist, who accused him of “one of the most amazing cultural swindles in American history.” (Ultimately this would become a question of copyrights, and of folklorists claiming authorship or co-authorship of songs that, most often, their informants hadn’t composed either.) Banished by Lomax, Leadbelly became a star of the Communist front — another instance of who’s zooming who — though the leftists were embarrassed by some of his more ribald songs. At this point something astonishing occurred. Zora Neale Hurston, the great folklorist, nursed ideas of cultural nationalism that bordered on the reactionary. For many reasons, personal as much as political, she hated the left, most particularly some of its black literary heroes, and none more than Wright. In the dramatic high point of Hamilton’s book, she reports how Hurston wrote John Lomax, both endorsing his right-wing politics and hatred of the (in his words) “largely Jewish” left, and spying on his son Alan’s flirtations with the Reds, and most particularly with Mary Elizabeth Barnicle, an Irish-American academic who would some years later marry a trade union leader. In Hurston’s view, the left had cast a double spell on Alan, sexual and political. The image of the gifted but tetched Hurston conspiring with the frankly racist Lomax against his son is worthy of a three-act play.

Alan Lomax contested his father on theoretical grounds as well. To his great credit he realized that recordings had not destroyed folklore but amplified it. He had noticed, as would many subsequent folklorists, that singers and musicians who gave dry, lifeless performances when recorded by the Library of Congress would snap to attention before the microphones of a Decca or Okeh. While folklorists lamented the loss of a special, spur-of-the moment, improvisatory charm — a forecast of the idea that “mechanical reproduction” changed everything — the artists themselves took it all in stride. They understood that recordings were, in current parlance, merely a “delivery system,” an advertisement for what they could do, and promised to do better after their recordings made them famous. Particularly in gospel and jazz, there was a compact between artists and fans that the recording merely initiated an experience that would be completed when the artists appeared in person. Whether single or album or MP3 file, the music remained a calling card, an advertisement for the self. Cantometrics notwithstanding, Alan Lomax’s great contribution may be his promotion of commercial records. Confronting both Lomaxes was Lawrence Gellert, a New York leftist who in 1936 published “Negro Songs of Protest.” Gellert, who was married to a black woman, felt that the Lomaxes had ignored a vital tradition of protest and impiety. Time Magazine (in an article perhaps written by James Agee, who was free-lancing for the publication at the time) quoted such antinomian lyrics as “Stop foolin’ wid pray, When black-face is lifted, Lord turnin’ away.” Gellert, a figure barely treated by Hamilton, was similarly audacious in using the politically incorrect language of the people; his fellow Communists were horrified by his abundant usage of obscenities and the N-word.

Hamilton does raise the question of obscenity when considering another group of critics, among them Frederic Ramsey Jr., Charles Edward Smith (a very perceptive writer) and the composer William Russell. They helped usher into print the memoir of Jelly Roll Morton, self-proclaimed “Originator of Jazz and Stomps” and “World’s Greatest Hit Tune Writer.” Some on the left — particularly Eric Hobsbawm, the great historian, who occasionally moonlighted as the jazz critic Francis Newton, a name that Hobsbawm chose to honor the very rare Communist musician, Frankie Newton — regarded New Orleans as “a multiple myth and symbol: anti-commercial, anti-racist, proletarian, populist.” But others exhibited the peculiar prudery of the far left. They were discomfited by the frankly sexual nature of Jelly Roll’s persona, his very name, his citation of Buddy Bolden’s “Funky Butt,” his casual observation that his only musical superior on the keyboard was Tony Jackson, a “sissy-man,” and, above all, his hilariously blue lyrics. Among the first blues he heard being sung by a woman were the lines “I got a husband and I got a kid man too / My husband can’t do what my kid man can do.” The Wife of Bath couldn’t have put it better, but Jelly Roll’s new audience was mortified. Even coarser by their standards, and buried for years in the vaults of the Library of Congress, was “Winin’ Boy Blues,” with its boastful line “I fucked her till her pussy stank.” (A recent Internet hit, “Smell Yo Dick” by Riskay, a female rapper, could serve as a riposte to Jelly Roll, a hundred years late.)

This was more real than the white blues boys had bargained for. As Hamilton shows, after being accused of vulgarizing the culture, they were sideswiped by McCarthyism. Dodging attacks on their left-wing sympathies and corrupt morals, they retreated to studying the music of the rural South. The product was a series of Folkways anthologies, filled with music undisturbed by a radical thought or sexual impulse. But this attempt to capture a factitious purity was doomed from the start. It has always been emblemized for me by a Folkways recording of a group of country girls singing a song about heaven. The annotators could be forgiven for not recognizing that it was a note-for-note copy of a popular gospel record by the Davis Sisters of Philadelphia. But how could they have transcribed “I’ll lay down this old sword and shield” as “I’ll lay down this old sewing machine”? And, even more risibly, describe this absurd lyric as “deeply moving”?

Hamilton’s last crew includes a group of men who dubbed themselves the Blues Mafia. Curiously in a world overridden with sexism, two gay men were the dominant figures. In 1964 Blues Mafioso Nick Perls, the son of an émigré art dealer, discovered the great country blues singer Son House, alive if not quite well, in, of all places, Rochester, N.Y. Within Perls’ affinity group, the dominant sensibility — apparently as much by physical as intellectual bullying — was James McKune, who is probably Hamilton’s favorite fan. An impoverished alcoholic who would die the victim of a sexual episode gone horribly wrong, McKune was the Mafioso with the most refined sensibility. While other collectors trafficked in irrelevancies like discolored record labels or scratchy-sounding reprints, McKune’s collection was comparatively small but exquisitely chosen. His focus was exclusively aesthetic. Politics didn’t signify: “After you’ve listened to the real Negro blues for a long time,” he wrote, “you know at once that the protest of the blues is … in the accompanying piano or guitar.” Listening as closely as he could, McKune determined that the ensemble of voice and instrument was most seamless in the country blues of Son House, Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson and Skip James. Patton particularly stirred him: “only the greatest religious singers have ever [affected] me similarly.” It should be noted that some of Patton’s best records were religious, and that the work of Robert Johnson or Josh White, arguably the most talented blues guitarist, is shot through with traces of religious imagery and vocal devices like growling and wordless moans that are brazenly churchy. (Elijah Wald has written superb biographies of both Johnson and White, making clear their broad musical perspectives.) In other words, even the best of blues listeners circumscribed the music’s range and durability.

To Hamilton’s surprise, McKune abandoned his obsession. Others would pick it up. Arguments of a Jesuitical precision would follow, denominations as vague as deep blues, country blues, Piedmont blues, Mississippi blues, und so weiter. Of course when everyone had been listening to the same records and had their eyes on the same prize, such distinctions would strike the actual practitioners, the blues singers, as bizarre. (Some academics entertained the French idea that something wasn’t real until it was actually named.) When asked whether his music was really folklore, Big Bill Broonzy replied that he hadn’t seen any dogs or mules sing it. In one of the most curious developments, blues singers, who had never been stars when they were young and strong, developed a whole new public when they were old and weak. Hamilton notes many disappointing encounters between the veterans and their youthful acolytes. The message seemed to be they pretend to pay us and we pretend to sing. Later when generations of white fans would study the blues veterans’ records and become virtuoso exponents of their technique, Muddy Waters would shrug and say they could outplay him but they couldn’t out-sing him. And, ever so often, coming up with the best note, hit exactly where and when, he’d outplay them too. This was made abundantly clear to me in the late 1960s when the Apollo Theater had a spectacular blues show featuring, among others, T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, B.B. King and Big Mama Thornton. All of them sang and played harder than I’d ever seen them do, whether at folk clubs in Greenwich Village or Cambridge, Mass. Confronting an audience that took rhythm and improvisation for granted, and expected them to work for their pay, these great artists delivered a blues that was realer than real.

While it’s easy to mock the blinkered vision of Hamilton’s crew, its members reclaimed a history that might have gone unrecognized. Reading her study, I was struck by the similarities between the moldy figs of yesteryear and the obsessives of today. Once rock ‘n’ roll was celebrated precisely for its popularity. But now many rock critics would agree with James McKune that the public’s taste is to be deplored; a Pazz & Jop poll almost never meshes with the Hot 100. The multifications of style from emo to screamo carry us back to the days when blues lovers could locate the fulfillment of their chosen styles within a few miles of country road. No obsessed fan is guiltless. (As the author of the first book on gospel music, I had the chance to define the genre’s golden age as running from 1945 to 1960. Now I think I was off by 10 years in either direction.) Reading of the Blues Mafia, I remembered those days of the 1970s when rock fans, as a means of keeping things real, destroyed albums of disco, a keyboard-driven music identified with women and gay men. By that time, Nick Perls, the man who rediscovered Son House, had switched his allegiance from the real blues to disco.

Hamilton occasionally glances at the reactionary implications of her characters’ pursuits. It’s not a surprise that champions of the past often end up politically conservative. In his memoir, Bob Dylan asserts that his political hero, all during the freedom-marching ’60s, was Barry Goldwater; and during his Pentecostal era (saved in a church founded by the former pianist of the blue-eyed soul duo the Righteous Brothers) he publicly excoriated homosexuals, Mr. Jones having gotten religion. One of the greatest fans of 1960s soul was Republican strategist Lee Atwater. Remember the image of him doing the soul split at a White House party, surrounded by a group of his aging idols, all his racist demagoguery placed temporarily on hold while he danced to the music. Hamilton includes a devastating quote from Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro” in which he praises the black man for “relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body … the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm.” (Jelly Roll Morton was never so vulgar.) You might be able to hear this as Wilhelm Reich meets the blues. But it reminds me of Mailer’s many abominable remarks about women and gay men.

But cultural reaction runs in all directions. Hamilton quotes a smart observation of the blues scholar Charles Keil, “I can almost imagine some of these writers helping to set up a ‘reservation’ or Bantustan for old bluesmen.” This is a stunning if unwitting echo of something Zora Neale Hurston wrote her professor, Franz Boas, in 1927: The Negro “is not living his lore to the extent of the Indian. He is not on a reservation, being kept pure. His negroness is being rubbed off by close contact with white culture.” That attitude may explain why Hurston joined the John Birch Society in the 1950s. Still attacking Communists like Richard Wright (sic) and James Baldwin (double sic), she sided with the South’s biggest racists in their opposition to integration. Predicting Clarence Thomas’ attack on affirmative action, she felt it was patronizing to assume that blacks would benefit from mingling their already superior culture with the outside world. In her despair over a vanished golden age, she was something of a white blues boy herself.

Anthony Heilbut’s books include “The Gospel Sound: Good News and Bad Times,” “Exiled in Paradise: German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America From the 1930s to the Present” and “Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature.” Albums he produced, by singers such as Mahalia Jackson and Marion Williams, have won the Grammy Award and Grand Prix du Disque and have been included in the Library of Congress’ National Registry.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.