America’s Political Pollsters Could Be Missing the X Factor in the 2018 Elections

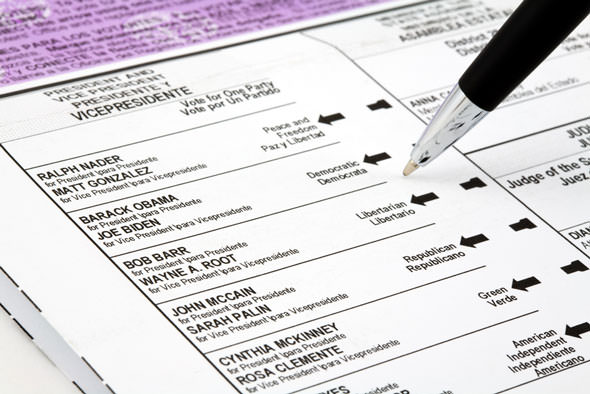

Pollsters have a hard time with a category often known as hidden voters. Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Four months after last November’s statewide elections in Virginia, Echelon Insights, a voter polling, data and analytics firm working with Republicans, finally knew how badly the 2018 electoral landscape was going to be for their party.

By March, the state of Virginia had updated its statewide voter file with who had voted in the fall election that saw Democrat Ralph Northam win the governor’s race by 9 points and the Republicans lose 15 seats in GOP-gerrymandered House of Delegates. Compared to the previous midterm baseline, Echelon’s analysis began by noting that Democratic voter turnout was up 16.7 percent, while Republican turnout was up 0.5 percent.

“The news was grim for Republicans,” their report continued, but especially so when it came to people who skipped primaries but voted in November. Turnout among these Democrats was up 14.6 percent, while for Republicans it was down by 9.0 percent. In short, Echelon’s report, which is a slick way to pitch its services to 2018 candidates, outlined the contours of the upcoming General Election’s blue voter wave.

“Turnout exceeded midterm benchmarks the most amongst nonwhites, particularly emerging voter blocs like Hispanics, Asians and those of another race,” it reported. “Female turnout was stronger in every group except for Asians. And overall, black turnout outperformed white turnout…”

Echelon conclusions were not that unique about what voter blocs to watch for this fall—especially since these are the very cohorts that have been insulted, offended or targeted in many ways by the president’s abrasive words and repressive policies. So why have a notable number of polls missed their ascension and impact in 2018’s primaries?

In Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s surprise defeat of Rep. Joe Crowley, D-NY, in June, the New York Times reported a pre-election poll three weeks out had put the longtime Queens political boss 36 points ahead. She won by 15 points—in an election where Democratic voter turnout was exceptionally low, with 13 percent of the registered party members participating, but where voting by non-whites was crucial.

In Florida’s late August gubernatorial primary, there was lots of polling, but almost none saw the energy and momentum of Blacks who turned out in record numbers across the state to help Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, an African-American, beat a crowded field of more centrist Democrats. A week out from that primary, polls predicted Gillum would get 12 percent; he ended up winning with 34 percent.

Hidden Voters, Mistaken Assumptions

Part of the problem with polls in these races—and this holds true for November—is that pollsters have a hard time with what’s often called hidden voters. That’s slang for people without voting histories. Some are new—or first-time voters. Some are registered but vote infrequently. And in low-turnout races like primaries, they are hard to detect, let alone reach for questioning over phone lines—especially younger people on digital devices. And if they are hard to detect, and hard to reach, then pollsters cannot adjust their raw numbers—which they all do—based on what they think mirrors the likely electorate.

“Polls missed youth turnout, and that happened in other races like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s,” longtime Democratic pollster Celinda Lake told Vox.com, when asked about what was missed by pollsters in Gillum’s race. “The campaign also targeted campuses that just got back [to school]. Polls missed the enthusiasm and solidification of the African-American vote and the base Andrew had there.”

Polling is an imprecise science, pollsters endlessly say. But as Echelon Insights’ March report makes clear, 2018’s engaged voting blocs are not exactly a mystery. No matter what will happen with Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination, you can be sure that women are watching and many will vote in November. In many other races, social media can offer clues about voter enthusiasm—although these platforms’ strengths for campaigns remain with targeting likely voters, not forecasting who will vote. (That is because numerous voters don’t post their political views online.)

The question that keeps emerging is who is not on pollsters’ 2018 radar. That matters greatly because between now and November’s vote, there will be a tsunami of horse race coverage delivered in authoritative tones. However, pollsters will tell you that their analyses are more vaporous; that they are merely snapshots in time of voter sentiment, in part based on answers given (that aren’t always true) and in part based on their assumptions about how big slices of this fall’s electorate will be.

This mix of statements, assumptions and math can be useful for campaigns in ways that the public will never see—such as deciding where in their districts they are weak, need to redeploy resources, where to send their candidate and buy advertising. However, what’s good for a campaign is not necessarily good for the public. That is especially true when media organizations treat their polls as gospel; don’t discuss their poll’s assumptions, strengths and weaknesses; and gloss over their margins of error.

That’s what happened in 2016, when, as almost everyone knows, polls repeatedly deemed that Hillary Clinton would be president. Obviously, that didn’t happen, pushing the American Association for American Opinion Research (AAPOR) to launch a deep self-examination and issue a detailed post-2016 report, whose takeaways are instructive for the fall midterm election. Particularly telling was the assumption department, where many pollsters tweaking raw results gave too much weight to college graduates widely supporting Clinton—thus underestimating Trump’s support. And then some slice of Trump’s base fell into that hidden category, because they were infrequent voters.

The result was 2016’s final national polls were largely correct—predicting Clinton would win the nationwide popular vote by 2 percent. She won by 3 percent. But the national picture is not the same as state-level polls, where, when all was said and done, Trump won by total of 80,000 votes in three states to secure an Electoral College victory in a race where 135 million presidential ballots were cast.

“Polling is really not going to help you with that—once you get down to small sample sizes, the chances of a fluke are too great,” said Colin Delany, Epolitics.com editor and a Campaigns & Elections columnist. “I think people are quick to say polls are wrong when they really weren’t. The Clinton-Trump race is a perfect example. It got the broad outline of the electorate right. It just didn’t get those 80,000 people in those three states.”

“Most pollsters, myself included, seeing the clear lead for Hillary Clinton in the national numbers, more or less forgot about paying attention to the Electoral College,” said Kathy Frankovic of YouGov, a respected national polling firm. “We assumed that a lead of two to three percentage points in the national vote would certainly provide an Electoral College majority. After all, it always had before! That’s a pollster problem.”

Additionally, Frankovic pointed to the AAPOR report that not only cited a paucity of polls in the three states—Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—but the mistaken weighting of college graduates. Polls in “some states neglected to use education as a weighting variable (most national polls did) and that underrepresented Trump supporters,” she said by email.

So how seriously should the public take polls this fall—amid all the horse race coverage to come? As 2018’s elections enter their final stretch, voters should be skeptical of overly definitive pronouncements tied to polls. That can be somewhat less true if the polls reach sizable numbers of people at the district level. But most of the more localized polls are closely held by campaigns and are not released.

That’s the takeaway after talking to consultants and pollsters like Delany and Frankovic. Polls have many uses for campaigns, the press and even the public. But they also have blind spots—which is why they are to be viewed cautiously as the election crests.

In 2016, those blind spots—what’s been loosely called hidden voters—included many Trump supporters. This year, it appears the voters that are hiding from pollsters—at least in the primaries—are the infrequent or new voters that are helping Democrats, especially non-whites and women. However, the final polls should be tighter, Frankovic said.

“I expect greater primary poll errors,” she said. “Voters are less attentive in primary campaigns and far fewer vote. They make up their minds later and pollsters can miss them.”

Single Polls vs. Averaged Results

Despite the caveats, Delany said the way some polls were presented were better than others. First, polls that relied on interviews—not automated calls or digital messaging—were better, he said. But the best approach was to average the results of polls, which can give you a better impression of a race’s momentum and direction.

“You can get a sense of a direction things are going,” he said. “Now, I’ve never been one to think that a half point in a poll is worth much. That’s why the polling averages by FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics are more useful, because they will even out the hills and valleys. But hardly anybody is doing that at the congressional level [in 2018]. You are lucky to get many polls.”

But even high-profile races, with many polls, have to be viewed provisionally. Take the U.S. Senate contest in Texas. The latest poll by Quinnipiac gives incumbent Republican Sen. Ted Cruz an almost 9-point lead. The RealClearPolitics average of 12 polls since last spring gives Cruz a 4.5-point lead. But even as Democrat Beto O’Rourke’s numbers seem to be climbing, the Quinnipiac poll only surveyed 800 people—with a margin of error of plus or minus 4.1 percent. That’s in a state with 15.2 million registered voters, where millions will vote in lowest-turnout years.

Where does this leave Cruz and O’Rourke’s supporters? The honest answer is hoping and working hard to bring out their respective bases, especially as midterm turnout in Texas has been historically low. O’Rourke has run an internet-savvy campaign. He is betting on more youthful and non-white voters, the exact cohorts that pollsters overlooked in some 2018 primaries and who are among the hardest for pollsters to reach (as they use mobile devices). But if Beto is behind by 4.5 percent, if that’s accurate, that’s still hundreds of thousands of votes short of winning—if one-third of the registered voters turn out.

If polling sounds like a 20th-century political campaign tool that has a hard time getting precise voter data, what about all the 21st-century micro-targeted data and personal profiles that websites like Facebook have compiled on users and sell to advertisers—including political campaigns?

“If we believe that social media targeting is based on the actual posts and shares of individuals, clearly they have more information at hand about a potential voter” than polls, Frankovic said. “It also extends over a longer period of time. That’s great for targeting. But I’m not sure how useful it is for prediction, especially when there are voters on social media who aren’t doing political postings at all.”

“All it shows you is activity,” Delany said. “Activity doesn’t translate into votes. It can. But so far it hasn’t consistently worked. Again, you will see people make claims—like Bernie before Iowa in 2016—that social media predicted it. But if you turn around the next month, it [social media sentiment] will be the opposite” prediction and result.

If anything, the best pollsters are trying to use a mix of traditional and digital tools to reach voters. If you look at the fine print of polls, the better ones will say they use actual callers—not robotic devices—to reach people, including on their cell phones. There are also polling firms that have used online panels to tray to gauge sentiment, or specialize with parsing social media data.

Not on the Radar?

But the biggest challenge facing pollsters, and indeed the campaigns themselves, in 2018 is what hidden voter cohort will drive turnout—or tilt the results into electoral victories. Simply stated, who is not on their radar—for whatever reason?

“Republican survival depends on strong, disciplined campaigns that keep defections to a minimum, and using analytics to identify and mobilize Republican voters at risk of sitting out 2018,” Echelon Insights said, pitching its services to Republicans. “Simply letting pollsters’ telephone response rates tell us may not be enough. Trump’s approval rating and the midterm ballot has improved in polls taken in 2018, but Republicans have continued to underperform in special elections to the same degree they did in 2017.”

It seems that Republican analysts like Echelon have a pretty sober view of the coming blue voter wave—and which voter blocs will be decisive. Whether that is true of the pollsters working for Democrats or major media organizations remains to be seen.

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.