|

To see long excerpts from “American Catch” at Google Books, click here.

|

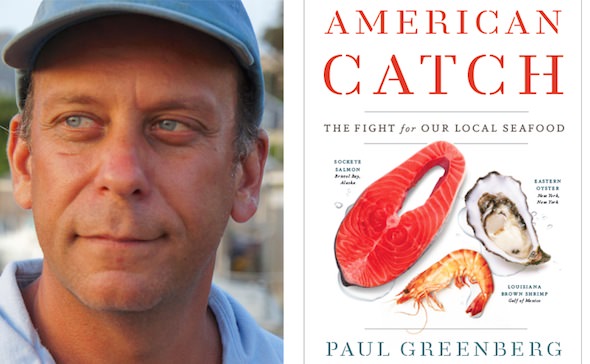

“American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood”

A book by Paul Greenberg

The United States is, increasingly, a coastal nation. It’s estimated that by the end of the decade roughly half of all Americans will live within 50 miles of a coast, and that doesn’t include the Great Lakes. Our government controls 13 percent of the ocean as our exclusive economic zone, more than any other country on Earth. But we define ourselves by the land we possess, not the sea. Terrestrial parts of the country get the highest form of praise: the heartland, middle America and so on. Our seafaring days are now in the distant past.

With his new book, “American Catch,” Paul Greenberg aims to change that mind-set. It is a call to arms, suggesting that the highest form of patriotism would be to embrace the bounty that can still be found off America’s shores, rather than relying on the imported seafood that graces more than 85 percent of our plates. We are, in his words, now “a seafood debtor nation.”

Writing about fisheries policy is, to put it mildly, challenging. It is one of the wonkiest aspects of environmentalism, especially when issues such as aquaculture, the mechanics of buying and selling fish, and reef restoration enter the equation. On top of that, the main characters — in this case, Eastern oysters, Louisiana brown shrimp and Alaska’s Bristol Bay salmon — don’t speak.

But Greenberg, whose previous book, “Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food,” made the best-seller lists, is skilled at finessing this challenge. He populates “American Catch” with several compelling characters, including autocratic mollusk researchers, profane water-quality crusaders and iconoclastic defenders of Alaskan rivers. These activists are all engaged in the fight to reclaim America’s seafood heritage or preserve what is left of it.

The book focuses on three species in three very different locales: oysters in New York City, shrimp in the Gulf of Mexico and sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay. The two strongest sections are the ones exploring Greenberg’s home environs of New York and Connecticut and the wilderness of Alaska; those sections speak to America’s past and its future.

A fine stylist, Greenberg evokes the glory days of New York City’s Fulton Fish Market. The market is now “weeping with water stains,” but a century ago, “clunky barges, flat-bottomed oyster skiffs, broad-beamed Hudson River sloops all made their way to this weigh station and docked at buildings that were inherently more geared toward the sea than to the land.” Various factors helped destroy this thriving trade: Developers — including our first president, George Washington — drained the region’s salt marshes, while polluted water poisoned local oysters so badly that they became a public health threat. Today 80 percent of the nation’s wild oyster reefs are gone.

But a cadre of area residents has not given up on New York’s estuary and the mollusks that used to dominate it. This group includes Andy Willner, the founder of an organization called the NY/NJ Baykeeper, who peppers his deeply philosophical musings with plenty of curse words. When his daughter asked him years ago on a hot day why she couldn’t go swimming off Staten Island, Willner wondered, “Why the f— can’t she swim?” Noting that the Clean Water Act had stipulated that all U.S. waters should be fishable and swimmable by 1985, Willner realized he had legal standing to challenge state authorities for failing to reach that goal: “If you can’t eat the oysters, why the f— can’t you eat the oysters?”

Others have pursued similar aims in slightly different ways. One was Victor Loosanoff, a Connecticut-based researcher originally from czarist Russia. Greenberg calls Loosanoff, who died in 1987, the “great oyster tamer” for his pioneering work in helping to promote the cultivation of oysters. Steve Malinowski and his son Pete have encouraged wealthy New Yorkers as well as local schoolkids to repopulate the waters with oysters. And Kate Orff, a New York water landscape architect, has coined the word “oyster-techture” in an effort to explain how more robust reefs could help protect New York City in a future when it will be subject to more intense and frequent storms.

Greenberg’s section on shrimp, while important, is a little less lyrical than the rest of this tale. It captures an important seafood trend: Half a century ago, 70 percent of the shrimp Americans ate were wild, but now 90 percent are an imported, farm-raised product that comes from Asia and Latin America. Greenberg visits two places to depict this shift: the Gulf of Mexico, which used to be the primary source of our shrimp but was battered by the 2010 BP oil spill, and a fish farm in Vietnam. While this part of the book has some appealing characters — including a Cajun shrimp broker who mocks the federal government’s attempts to find him a different line of work after the spill — Greenberg’s detailed discussion of shrimp aquaculture is not as reader-friendly as the rest of the book.

When it comes to the conflict over whether to allow the construction of a huge gold and cooper mine near Bristol Bay, Greenberg puts himself firmly into the fight. Some years ago, he journeyed to Capitol Hill to make the case for blocking the mine on the grounds that the operation’s waste could clog rivers that supply nearly half of the world’s sockeye salmon. A reception at the Supreme Court was arranged, and Greenberg made the mistake of attending it wearing his fishing hat. A “slightly indignant older woman” yanked the hat down over his eyes and suggested he take it off while in the court; it was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Greenberg mentions in passing the arguments being made by the mine’s sponsor, the Pebble Partnership, but he is not heavily invested in doing a traditional back-and-forth. From his perspective, the stakes are too high. Referring to the Environmental Protection Agency, which is weighing whether to block the project under the same Clean Water Act that Willner used to help clean up New York’s waters, Greenberg writes, “If [the EPA] does nothing and allows Alaska to continue with business as usual, Bristol Bay could end up much more of a minerals extraction system than a food system.”

He captures the vibrancy of this abundant, powerful food source not just through his own tales of fishing — such as one in which rainbow trout literally slip through his fingers, only to be recaptured — but also with the hectic rush of a small, commercial crew cramming its boat full of fish before the season closes. It is a miraculous bounty that will replicate itself indefinitely — that is, if we start taking better care of it.

Juliet Eilperin is a White House correspondent for The Washington Post. She can be reached at [email protected].

©2014, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.