America Keeps Getting China All Wrong

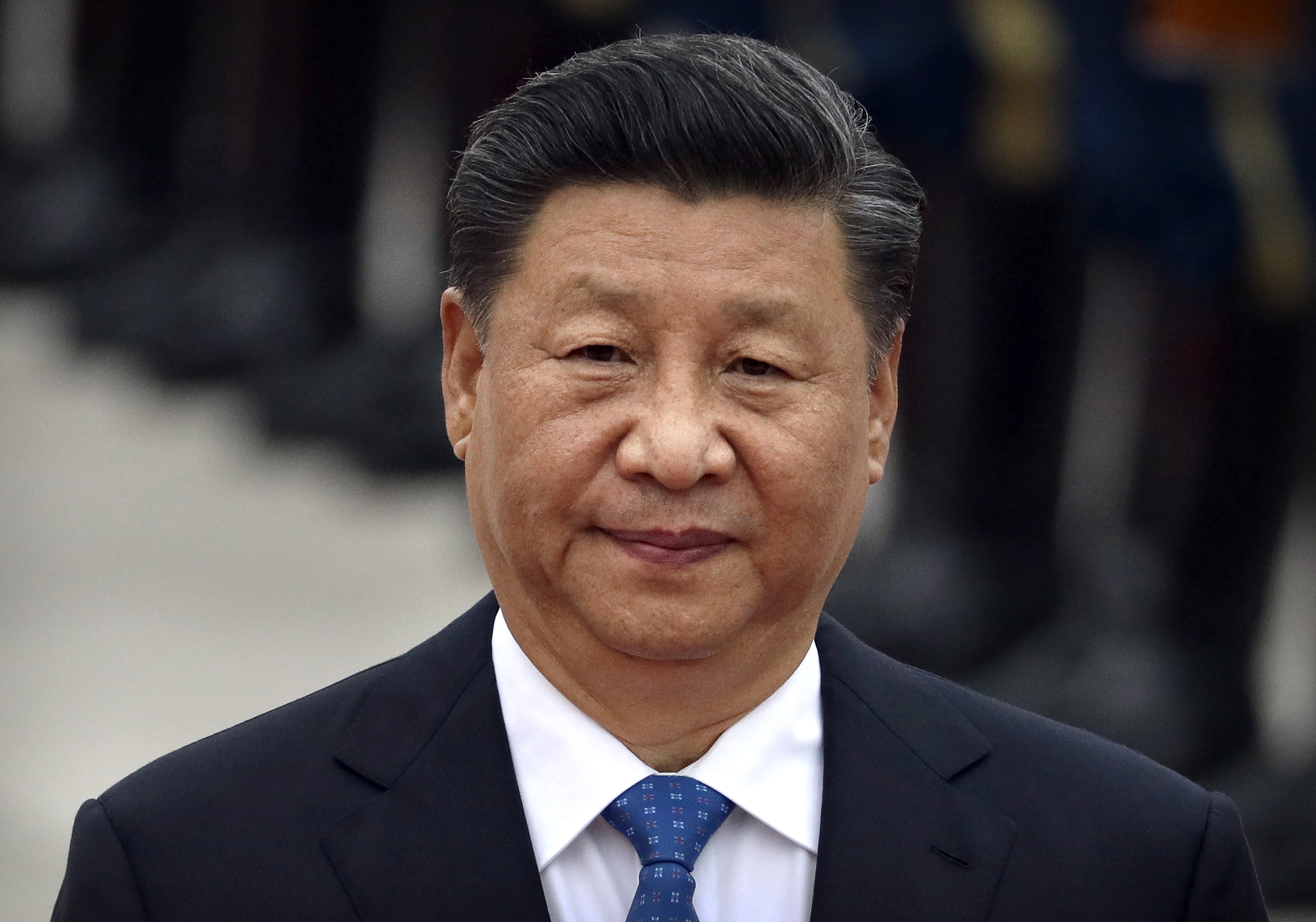

The two international giants are linked in inextricable ways, yet Americans’ understanding of China consistently lacks nuance. Chinese President Xi Jinping. (Mark Schiefelbein / AP)

Chinese President Xi Jinping. (Mark Schiefelbein / AP)

Listen to the full discussion between Dube and Scheer as they delve into the complicated and at times bloody history between China and the U.S. and try to come to an understanding about where this relationship is heading. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Introduction by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case it’s Clayton Dube, who is the director here at USC of the U.S.-China Institute, and who has been involved with China ever since he went there in ‘82. And learned the language, became a leading expert on it. And what’s so interesting about the location of your institute here at USC is I think we have here 7,000 Chinese students–from China, not–

Clayton Dube: Not quite 7,000, but last year 5,600. So a significant percentage.

RS: And I think it’s the largest–

CD: We’re in the top five. Yeah, we–some of the engineering schools in the Midwest top us.

RS: OK. So at any rate, one of the things that’s interesting about teaching at USC in the middle of all these demonstrations in Hong Kong, and now the tariff war that President Trump has going with China–I find–and it would be simplistic to say, oh, they’re just saying that because they come from an unfree country, and have to watch what they say. But I find that our students from China, just as our students from India or anywhere else, are quite independent. And some have been here a long time or what have you, but I don’t find them an intimidated population at all. And yet I find a lot of mixed feelings about what’s happening in Hong Kong, which some of them at least see as a privileged place with its own history. And also about the tariff war with the United States, which they tend to think is quite punitive and one-sided. So what I really wanted to get you in to talk about is something that I’ve had you talk [about] in my classes and so forth, is comprehending China. And just to put my own oar in the water here, I was in the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1963, I believe–a long, long time ago. And trying to learn the language, and then I went to China during the Cultural Revolution; I have some familiarity with the history. And I am amazed at how often and consistently we get China wrong. And I just think back at that time, China had–this was ‘63, ‘64–about, what, 400 million to 500 million people. Is that correct?

CD: Ah, probably closer to 650. 650 million by the early 1960s. At the time that the communists came to power in ‘49, they did a survey, and the population was about 583 million.

RS: OK. 583 million. Now you have 1.3 billion people in China. And I remember at the time when I was a student, the conventional wisdom was that China had too big a population to be able to develop. They were resource-poor, the land was exhausted, they had no other source of fuel than coal, and that would clog the cities and so forth–which has turned out to be true, as far as coal. And just generally a very pessimistic view. It was Ehrlich who wrote The Population Bomb; I think he was down by Stanford or around there, Paul Ehrlich. And he talked about the world’s overpopulation, and it’s still a big problem. But the fact is China has probably, what, 800 million more people than it did then, and there’s no question that it’s a far more prosperous country. And they have found the wherewithal. And the other myth about China at that time was because it had had this Communist Revolution, which was assumed to be very radical, more so than the Soviet revolution–and that they would never change, and you had to be in constant war with them. After all, the Korean War and the Vietnam War were fought primarily against China, and these were just supposed to be the surrogates nearby. And yet China has gone through the most remarkable change. Still run by a Communist Party, you know; so you could say, well, they’re driven by their texts–but clearly they’re not. And they’ve been very pragmatic capitalists, and very successful, and hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. So kind of–you’ve been familiar with this, not quite as long as I have, but you’ve been more on the scene, living years and years in China. So just kind of give me your bird’s-eye view of the development of China in the post-revolutionary period.

CD: Well, there’s a lot to say. China–in fact, this year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. And people in the West, especially, tend to divide China into two big periods: first the Maoist period, and that’s 1949 until Mao dies in 1976. And this includes a lot of political upheaval, considerable movements, things like that, where you do have some economic changes that would set the stage for the dramatic rise that we’ve had since Mao’s death, but the big changes came after his death, and especially since 1978 and 1979, when the Communist Party embarked on significant reforms. And so this year, in fact, we’re marking three big anniversaries, this year and last. So in 1978 and 1979, you had first–and probably most important–the economic reforms. And this was not a big bang; they didn’t have it all figured out. They made some small steps, and over time advanced in terms of opening their economy and permitting greater flexibility for people to choose their own economic paths. And so that’s 1978. Also in 1978, you have the establishment of diplomatic relations with the United States. And that’s, of course, important for the flow of capital, expertise, and the opening of the American market. So that’s–

RS: OK, let me put a little pizazz in this. Because really the critical figure was Richard Nixon, a man not held in high regard because of Watergate. He did some terrible things–the bombing of Cambodia and the expansion of the war in Vietnam, and so forth. I’m not forgiving his war crimes. But it’s one of those great contradictions of American foreign policy, of which we have many. At the same time we’re fighting in Vietnam, and we’re killing millions of people–a conservative estimate, I think, would be about 3 million were killed, and 59,000 Americans; we played havoc, we carpet-bombed the country–no one could ever claim that Vietnam represented a military threat to the United States. The whole claim was they were surrogates, somehow, of China. And then in the middle of this war, of Nixon’s war, he goes to China and makes peace with what was supposed to be the bloodiest communist leader of them all, Mao Zedong; he has drinks with him, and so forth. Still continues this war against the surrogate, supposedly, of China, in Vietnam–a totally irrational exercise. And we go through years of debate about “We can’t just get out of Vietnam, and if we get out of Vietnam they’ll fight us in San Diego, and we’ll have havoc and so forth.” We lose in Vietnam– “we” being the United States government, loses in Vietnam in the most ignominious defeat in American history, people lifted off the roof near the embassy and what have you. And what happens? The Vietnamese don’t turn on the United States, they turn on China. Communist China and communist Vietnam go to war after the defeat of the U.S., and have this big fight about their borders. And they’re still arguing about islands and so forth, two communist governments.

So there was nothing monolithic about communism; there was nothing really that they had much in common. They certainly were not an international movement to do us in. And both of them, still communist governments, have embraced a free-market model that is quite open and effective. And in fact, a big threat now is people are saying, well, if we can’t do business in China because they won’t accept our reasonable trade agreements, we’ll just swing it over to Vietnam and some other countries like that. But mostly Vietnam comes up in the discussion. And there is in fact a battle, not between Vietnam and the U.S. or China and the U.S., really, but between China and Vietnam, about who’s going to put more stuff into Costco or Walmart. So I want to ask you as an expert, and somebody who teaches this stuff and knows about it, how did we get China so wrong? I mean, again, going back to when I was in the Center for Chinese Studies, not only did they think physically China could not develop, but they thought that their ideology would prevent that from happening. And yet we look back on something–I happened to be there at the tail end of the Cultural Revolution in China. And you know, it was pretty clear to me that part of the Cultural Revolution created the basis for what came after, because it challenged the authority of the party, and so forth. So you might reflect on that–where is expertise on China? How did we get it wrong so long? And are we getting it wrong now?

CD: Oh, there’s so many questions there. To focus on the one that you conclude with–are we getting China wrong–I think that we definitely need greater expertise on China. And China’s not unique in, you know, America getting it wrong. I mean, we’ve gotten a lot wrong. But China is a large, complex, diverse country. And our understanding of it necessarily needs to be much more nuanced. And so to go back to something that you just brought up, and that’s Richard Nixon–Nixon, even before he became president, wrote this well-known article in Foreign Affairs where he said: we need to find a way to bring China in. China is too big to be outside, left to its own devices, scheming on its own. We need to engage China. Now, Richard Nixon had no illusions about changing China; that wasn’t his objective. And so some people today think that Nixon and everybody since then got China wrong, that they wanted to create a liberal, democratic China. But I assure you, Nixon had no expectation that that was going to be the result of his outreached hand.

RS: Let me tell you what Nixon expected. And [Laughs] it may shock you to know this, but I actually went and visited with Richard Nixon in 1984. He’d written a number of books after he was forced out of office, about détente, about peacemaking and so forth. And he traced his–he did it in his books, but also in the interview I had with him–and the reason he invited me to come talk to him is I’d written a kind of a revisionist article that Nixon did get something right. And mostly it was Eisenhower’s influence, and Eisenhower understood that the main construction of the Cold War was irrational. There was not an international communist movement; communism was a nationalist phenomenon. And so the Russians adopted it to their purpose, including a Georgian like Stalin, who suddenly decided he was all Russian. And they adopted it, the Chinese adopted it to their purpose; so did the Vietnamese. And there was never this bogeyman of the international communist movement with a timetable to take over the world. That was fraudulent. And the people in our government who were in the CIA, they knew it–they just didn’t talk about it very much. So there was this mythology.

And what Nixon argued in that–I’m really happy that you mentioned that article, because a lot of people credited Kissinger with the breakthrough with China. But you’re absolutely right, Nixon–and he told me that he hadn’t even met Kissinger when he wrote that article. But he was responding to–within the Council on Foreign Relations, they had a whole series of books about thinking about China. And it all had to do with getting China wrong. That in fact, it’s a nationalist movement, and it is capable of change and so forth. Right? And yet, again, I bring up–we’re still bombing, killing people in Vietnam because we say they’re communists and therefore the enemy. And the irony of Richard Nixon, who had made a career on his anti-communism and red-baiting and everything, being the person–no democrat would have dared to go over there and drink with Mao. And to remind people, you know, who grew up with this other view of China as kind of a producer of all these products and everything, we had a view of them as the little red ants and all that, and they were incapable of thought, and they were inherently violent. It’s all wrong, right?

CD: We got a lot wrong. And especially in terms of kind of mass media, this sort of thing. Conveying these complicated truths, that the world is much more nuanced. That Vietnamese communists have no great love for Chinese communists, and Chinese communist have no great love for Soviet communists. That sort of thing, that sort of nuance, was something that started to penetrate government in the late 1950s, but becomes more commonplace. And so you have some people who begin to see both the Chinese revolution, which had long since taken place, and the Vietnamese revolution, as being bottom-up. As being driven by domestic, by internal contradictions, internal tensions. And so those people were in a position to argue: look, we need to understand these as separate entities, as having distinct histories, distinct priorities. And while there might be something called the common turn, it doesn’t dominate what’s going on.

RS: Oh, it had no power whatsoever. You know what I think is interesting, that–because we have it now with Donald Trump. We always have a view of American innocence, Western innocence, and so forth, OK. Generally, you know, we make mistakes, but we’re not evil. So, killed a lot of people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but you know, there were policy considerations. We actually tried to save lives, and yes, mostly children and innocent people got killed. We feel that way about everything. But the irony here is that it’s really a quite destructive view. And at the core of it is we deny everyone else’s history, OK. And that includes their own nationalist feelings. And I was reminded of that. I just went and didn’t do heavy research, I just looked up Wikipedia on the Opium Wars today, because I was going to–I’m writing something on the side, and I was going to come talk to you. And it seemed to me, this current issue with the tariffs and Trump is an echo of the Opium War. Only the Opium War, to remind people, started in the early 19th century, goes up to about, what–

CD: The Opium War is really central, certainly to understanding what’s going on in Hong Kong, but also to understanding China, and how China–how the Chinese government represents itself to its people, but also the image that it wants to project beyond the borders of China. It starts in 1839, it concludes in 1842. If you are Chinese, and you study history in school, modern Chinese history begins in 1839. That’s the intrusion of the West. And that period of Chinese history, according to the leaders in Beijing, comes to a conclusion only in 1949, when they take power. So you have 110 years of feudalism and imperialism, oppressing the Chinese people. And so in 1949, when Mao and the others come to power, they say: That’s over. And that’s going to be celebrated in just a couple of weeks, on October 1. Because they’re going to say, hey, for 70 years, no one has pushed us around.

RS: Well, it’s more than being pushed around. I mean everybody forgets, again, how evil we can be. “We” being England, you know, as well as the United States; it’s primarily England in this. But the reality is, we were drug pushers. Everybody forgets that. This is–you know, right? We were basically, wanted their silver and silk and things that they had, and we undermined their will to resist, and we tried to corrupt a population very deliberately, and our Western missionaries justified that as saving souls. And so you couldn’t have a more grotesque image–I don’t think you have to exaggerate it. I mean, here the Westerners came in with this drug to destroy the very fabric of the society, right. And they fought a war and were willing to kill people for their right to do that kind of commerce. What they really were doing was stealing.

And I want to bring it up to Trump’s tariff wars and everything now, because I think it’s a parallel. And basically what has happened is a deal was made with the Chinese communists that we can do business, we can live in the same world. And we, the United States, supplied ideas, investment capital, terms of trade, and so forth. And the Communist Party delivered a docile labor force. And that’s ironic, because they were supposed to be the party of the workers and peasants. But the fact is, China became a factory floor for the world because the communist government was able, basically, to prevent unions from being disruptive. And to keep, and to handle the enclosure movement as in England, in a more peaceful way of getting people from the countryside, and particularly women, to work in Apple plants and so forth. And then when some of them jumped out and committed suicide, that was papered over; you know, there wasn’t investigative journalism and all that. And so a pact was made that China became the basis of easily exploited labor that turned out to be quite skilled, in a lower level of skill.

It seems to me the big tension now is that the Chinese feel–well, we got a lot of people here. We have pent-up demand. They want to consume on a higher level and not work quite in the low level. And people got a lot invested in education, instead of they’re going over to Silicon Valley to work. People from India do, and China do. No–we’re going to get to the next stage, and we’re going to do 5G communication. And we’re going to do, you know, figure out driverless cars, and we’re going to have cities that are wired and all that. And ironically, again, they seem to be better at some aspects of it. Four of the top 10 internet companies or communication companies in the world are Chinese-owned. And in particular–and I’m going to mispronounced Huawei, maybe you could help me there–but this company that we’ve decided to demonize is really doing what major capitalist companies, particularly in the telecommunication industry, have done: try to carve out areas of some kind of cartel or monopoly power, try to get every bit of information by hiring people or what have you, to advance. And they are threatening now to some companies here because they are good at it. Right?

CD: Well there’s, again, in your narrative, you’ve highlighted a couple of vital points. And the first one that I would point to is what happens after Nixon. And more important, after the establishment of diplomatic relations, which really facilitates investment and trade and things like that in 1979. And so you have the opening of the American market to Chinese products, and the opening of the Chinese labor force to American companies, as well as Japanese and everybody else. And so because there was so much cheap labor–because there wasn’t competition for this labor. There wasn’t competition in the sense that you had a whole lot of places where you could go and get a better job. And so you accepted relatively low wages, you know, at the town nearby, and you stuck with that. But China today is being pushed–the Chinese government today is being pushed, first, as you highlighted, by its own people. That these people want to live, and expect to live better lives. They’re quite conscious that just because you produce products that are exported to the West, doesn’t mean you can afford to buy them. So they want that, but also the government itself recognizes that it has a problem.

And the problem is that China has actually topped out in terms of its population. It’s topped out in terms of its population, its labor force. And so what it needs now is to make people more productive. And that’s going to take innovation. And as you have already highlighted, some of the most innovative companies in China are in the internet sector. And this includes Huawei. And Huawei–someone once asked me, is Huawei the Apple of China? And I said, no, no, it’s much bigger than that. It’s not bigger in terms of market capitalization, but it’s much bigger in terms of its importance in the global internet economy, but also within China. It is the number one handset manufacturer, so in that way it’s a rival of Samsung and Apple and others. But it’s also the number one network provider. It’s the company that makes it all work. It produces the switches and the systems that make the internet function, including this next generation, this 5G communication that we hear so much about, where they’re a leading player. There’s no one–

RS: Well, the Wall Street Journal in one recent article said they are not a leading, they are the leading player. And I don’t know how you run that down completely, but they’re certainly right up there. And the fact is they are contributing in European [infrastructure], everywhere–not just in China, although the Chinese market is very big. It’s ironic that they are now challenged by Donald Trump as–not just that they steal things, which I would assume Donald Trump when he builds hotels steals a lot of ideas and technology; that’s what’s called capitalism. But the fact is, he says the Chinese government will have access to their information. Here, the U.S. government has set a model for the world, right? We have been the pioneers of using ostensibly private companies, right, like Apple and Google and so forth, to collect information, then grabbing that information whether they like it or not, hacking into their fiber-optic cables, and getting conversations of the German chancellor or the Brazilian leader or what have you. So we have set this model. And now we dare say–I mean, I’m still amazed at the arrogance of our culture. We dare, after the Snowden revelation and everything, say this Chinese company is suspect and should not be trusted, because their government might do what our government does.

CD: Well, and in fact in 2013, when Edward Snowden went first to Hong Kong and then subsequently to Russia, that was–that point was very clearly made. And the Chinese were aware of, you know, the power of American intelligence agencies being able to penetrate defenses, and this sort of thing. And Snowden just made this clear. And in fact, one of the things that came out is that the United States had been working to do to Huawei what we accuse Huawei of doing. So we were looking to place our own software within Huawei’s systems, that would allow us to monitor Huawei in the way that they are now being accused by some in the U.S. government of doing to everyone.

RS: Right. But what it is is a denial of the value of multinational corporations. It’s a denial of the strength of international capital flows and capitalism, because of what–and we are the ones that betrayed it more visibly than anyone. But if what you’re saying is that Apple has products that can be subverted by the U.S. government routinely, then why should anybody in China buy an Apple product? And yes, you know, and the fact is, most of these products which we say you should trust are manufactured in China. But we draw the line at a company that happens to be Chinese-owned, you know. And I just think we’re at, again, another one of these irrational moments in thinking about China. Because one could say–one could say from a humanitarian point of view, it’s a wonderful gift to humanity to have so many people in China who you had given up as they should, oh, it will always be poor, they’ll always be subject to the most wretched conditions. No–they’re finding more meaningful work. And in fact, you know, this communications–there was one story I read in the Wall Street Journal, they actually extended 5G on an experimental basis to a truly rural, ethnically based community. And here are these people who didn’t even have glass windows in their houses, nonetheless were watching the latest opera and ballet and sports spectacle and so forth on a rapid, you know, transmission of information. So you would think on a humanitarian basis, we should be thrilled that not just China but India or any other country is developing. And instead, we’re back in that narrow-minded view of the nation state, that their progress is to our detriment.

CD: I think zero-sum thinking is the great challenge of our day. And unfortunately, I see zero-sum thinking in many capitals, not just the United States. And so with regard to, you know, we should be happy that our fellow human beings are living better lives–absolutely, that’s true. But in fact, American business has found great pluses in Chinese consumption. And so many American companies produce in China–not just for the American market. They do that, but they’re mainly there because there are hundreds of millions of potential consumers in China. And so we see that from fast food, where Yum Brands has KFCs that earn–that have four times on average the revenue per store in China that they do in the United States, to giants like Procter & Gamble, which have half of the shampoo market in China. So American companies are in China primarily, now, to serve Chinese customers. And of course, in serving Chinese customers, that’s good for their bottom line. And so if you happen to be a shareholder of those companies, you benefit, too. And so in fact, the rise of living standards in China has been a boon not just for the Chinese, but for Americans and people all over the world. And we see that, certainly, in terms of the consumption of American-produced products that are sold in China and sold here to Chinese. And so we see it–for example, California is routinely the number one exporter of goods and services to China. And so we see that in terms of a company like Tesla: its number two market is in China. We see all sorts of things like this. And so improving conditions in China has been good for American business as well. And so thinking zero sum, that if China exports more to the United States than the United States exports to China, is–every economist will tell you, it’s not economically significant. But also, any political economist would see that there are big advantages in having these cross-border flows. And that we have profited. And certainly you began by mentioning how many students we have here from China in the United States. The opening of our two countries–

RS: Well, we have generally in the United States, but here at USC, yes, it’s one of the ways this university has become one of the more important universities in the country, because we are able to attract these students. You said 5,600, what is that–that’s probably one-sixth of our student population.

CD: Yeah, one-sixth, one-seventh. It’s a huge share. And at USC, the mantra is we want the best students wherever we can find them. And so it’s a good thing that we can have access to students from China. And that has improved the situation here, because it’s one way to globalize a campus. There are a lot of good ways to do this; sending more American students to China is something I’ve long advocated. We are lagging terribly in this regard. But by bringing students here, and having them meet with Americans from all 50 states–that’s a good thing, not just for the Chinese students, but for the American students. They have a chance to break down some of these barriers, and to begin to understand Chinese as human beings with wants, needs, desires, aspirations, fears, just like everybody else. They may not be identical in those spheres and identical in those aspirations, but they’re just people.

RS: Well, and you know, you point out a couple of areas where we are interconnected. I mean, for example, Tesla selling cars in China. One reason they’re able to is because China understands that they have to have electric cars, and other cars that are not as dependent upon, you know, fossil fuels. Because they can’t breathe. And yes, and so–and we also know that the air quality in China has a lot to do with the air quality in Los Angeles. So it is the same. I think what is happening–and then, you know, we’re going to run out of some time here. But I think it’s a really important subject, is that the best side of capitalism–capitalism has an ugly side, which is grabbing resources, exploiting labor all over the world, divide and conquer, cause wars and everything. I’m not going to whitewash that. But on the other hand, at its best, when you increase and satisfy the aspirations of people–you know, Karl Marx said in the Communist Manifesto, capitalism ended the idiocy of rural life, and build the big cities, and so forth. And that adds to the well-being of everyone in the world, right? I mean, if the Chinese can get the electric car, right–which they are, by far, the biggest electric car market–then that’s a benefit to us. That’s the only reason we have the Chevy Bolt here, which I happen to drive, an electric car, because it was made for the Chinese market.

So I want to ask you, as we conclude this, to what degree is Hong Kong–which we haven’t talked much about, haven’t talked about it at all. To what degree is the turmoil, the protest–as somebody who’s participated in protests in the United States for much of my life, I identify with the students and not with the police, who are coming at them with batons. But on the other hand, I know that in this country, if we ever went to an airport, or if you blocked a major–it’d be quite brutal in repression. So there’s a lot of, you know, people saying, oh, look how terrible Hong Kong is–and as I say, I applaud the students, young people who are objecting to, you know, authoritarian power and demanding more freedom. But it’s a double standard, I think, because first of all, we don’t address that in Saudi Arabia or any other place. And I just wonder, to what degree–recalling how Hong Kong was this outpost of English imperialism, and its special relation to China. Are we not actually sticking our finger in their eye now, in a way? These–you know, right now in the Congress there’s a bill that will penalize, you know, China, Hong Kong and so forth. I mean, have we no shame given the–what we’ve just been talking about, going back to the whole history of China, and the unnecessary wars and deprivation. How do you assess Hong Kong? I don’t mean to put you on the spot, but go for it.

CD: Well, first, when you ask “have we no shame”–and the answer is obviously no. Your expectations of politicians may be misplaced if you expect them to be driven by that. But I think that what we have to first of all understand is, you know, Beijing makes claims that the problems in Hong Kong have external origins that the United States and United Kingdom are stirring that up as a way of weakening China, as a wedge into holding China back. And there’s no evidence of that. What’s driving the protests in Hong Kong are Hong Kong-specific issues, and Hong Kong-specific history. And again, that’s where a little bit of nuance, a little bit of knowledge, is really helpful. It’s important to keep in mind that many of those who are in the streets were not even alive when Hong Kong returned to Chinese control in 1997. And so what they are being–what is driving them is not some romantic idea of what British colonialism was like. Rather, it is a feeling that they’re being denied. That promises were made: universal suffrage, direct election for the chief executive; that Hong Kong’s government should represent Hong Kong, should serve the interests of Hong Kong. They’re anxious to preserve the civil liberties that they enjoy. They don’t enjoy–they do enjoy free speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of conscience, all of these things, and they’re exercising these rights today. But they don’t have the ability to choose their government directly. And that’s what they’re now calling on. And that’s where the tensions are.

Underneath that are two other big issues. One is that increasing familiarity with the mainland has not brought love. In fact, increasing familiarity with the mainland in Hong Kong has resulted in young people in Hong Kong increasingly seeing themselves as distinct. And so they are identifying themselves as Hong Kongers, as opposed to first and foremost Chinese. And if you’re part of the 1.3 billion people in China, that’s seen as an offensive, an offensive take: you don’t want to associate yourself with us. And so there’s this kind of built-in identity resentment that is present. On top of that, you have economic tensions. And so housing in Los Angeles is incredibly expensive. And so by some estimates, the median house, single-family home requires something like nine times the median household income to buy it. I’m not sure that I believe that statistic, but in any case that is the one that’s given. In Hong Kong, it’s more than twice that. And so many people see shrinking economic opportunities as well.

So there’s a lot of anxiety. And as a consequence, when the Hong Kong government seems to be doing primarily Beijing’s bidding, and not the bidding of the local populace, there’s resentment. And that’s what brought people into the streets. Now, once they came into the streets, and they encountered the police, and there was violence, and violence was returned, and these sorts of things–now you have additional demands. For an independent inquiry, for relabeling these protests as protests, not as the government–and especially the government in Beijing does, calling it riot, calling them riots. These kinds of designations have power for the people in Hong Kong. This is a very difficult, difficult moment.

RS: But this is true everywhere. I mean, you know, Ronald Reagan called people at UC Berkeley rioters, and a couple of–one was killed, James Rector, and others were shot and so forth. And he justified that. And, you know, I–some of these scenes, like if people seized an airport in the United States–I mean, it would be martial law, or there would certainly be very strong response. But I’m not defending that. What I’m just wondering–there’s a lot to criticize in every society, and no question, you could criticize a lot in China. But it’s interesting how Tibet, or the treatment of Muslims in one area, and now Hong Kong–which also has been the recipient of a lot of development, and no question what would happen to the economy of Hong Kong if it’s cut off from China and so forth. You know, in some ways, it’s a gateway–not in some ways, basically it’s a gateway to the society. But it’s–that, I think that’s fine; we should call attention to any grievance that anybody has.

But I want to get back to the thing we began with, this 1.3 billion people who live in China, the real China, OK. And there are issues there that never get raised. So let’s take a little few minutes. For instance, with all the talk about trade and everything, we never talk about their right to be in a union as a human right. Their right to protest their economic, or what are the safe working conditions related to the production of products for the American market. There, we could have a lot of agency–“we” being American consumers, the American media. You know, OK, Apple came out with its new phones, it came out with new things, we’re all dazzled by them. Well, we have very little reporting, or I think concern–how do the people live who manufacture these products? What are their rights, OK? And you know, so it seems to me once again, the human rights standard is used in a very artificial way to support one narrative or another. But the real question is–and it oddly enough came up in the renegotiation of NAFTA. I don’t know whether Trump was even aware of it, President Trump, but the fact is for the first time, there’s an insistence on a minimum wage. That if you’re working on cars that are coming into the U.S. market, you have to make 16 bucks an hour, at least for 40% of the car. And also local courts have control over that, and so forth. These are two major–they’re not even mentioned in the trade discussions with China.

CD: They should be. And in fact, one of the important issues is the rights of labor. And in fact, there has been attention to this, but it’s been episodic and not sustained. And so when some workers at Foxconn commit suicide, we pay attention to that, we link that to the production of Apple products and everything else. And so we need to have a much more sustained look at China. And when we look at labor conditions, we have to be mindful of the limited rights of workers. And you have those limited rights primarily because the Communist Party insists on controlling every organization. And for the most part, it’s mostly concerned with increasing economic output, and it’s not primarily focused on improving labor conditions. But we do see worker protests, we do see worker actions for better labor conditions to ensure that the wages promised are paid, that sort of thing. And workers are very much focused on wanting to have legal protections in this regard. And so supporting that, and paying attention to that, is something that’s really important. We need also, of course, to be aware that there are factories in places using workers who are being coerced into it, and are not paid standard wages. We have to have an expectation as consumers to use the power of our consumption, to insist that Walmart make sure that its suppliers produce these goods in factories that are safe, factories that treat workers decently, that sort of thing. And there has been actually some back-and-forth with the American labor movement. SEIU actually sent representatives to participate in organizing Walmarts in China–in China–

RS: That’s the service employees union.

CD: Right, the–

RS: One of the more progressive unions. Well, this is encouraging. And maybe also because when you can breathe in Beijing, you care more about the environment, and hopefully there’ll be a more robust environmental movement in China. Yes.

CD: I just wanted to say one thing the air–OK, well, let me have just a couple of sentences here. And the first would be you’re absolutely right, that the air in Los Angeles is influenced by the air coming out of northern China. There are estimates that 25% of the particulate matter in the air in California has its origins in China. But of course, that bad air in China is produced by factories often producing for the American market. And so we have not only outsourced production, we’ve outsourced pollution. And this is important to keep in mind. Chinese are hyper-conscious of this. If today is an average day, more than 4,000 Chinese will die prematurely due to air pollution. So that’s why the government is responding. And that’s why the government’s making this big push into renewable energy technology, solar wind in the common. And that’s why they want to increase the efficiency of the machines that they use, so that they draw less power and pollute less. And that’s why they’ve made this big bet, this big investment in electric vehicles and that sort of thing. And that is absolutely, absolutely vital. But with regard to the United States, and you know, connections here, we have a tremendous opportunity going forward. And it’s important that we seize it. Working together, the United States and China–and we don’t want to be Pollyannaish about this–we have accomplished important things. And we have addressed the real needs of people on both sides of the Pacific. We have the capacity to work together for good, and we have the capacity–by talking past each other and not engaging each other–to miss tremendous opportunities. And that’s what I’m worried about today.

RS: Yeah, and we should keep in mind, the reason I began with the Opium War, we’re not the only people who have a sense of our own history and what we’ve suffered, you know. And we’re recording this on the anniversary of the attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and all the radio I was listening to talked about it being, you know, this horrible tragedy. Well, the Chinese have their tragedies, and war is inflicted upon them in terrible ways. And you know, don’t forget, this trade issue was absolutely critical to a great human rights sacrifice in China, and the immobilizing of a whole population throughout much of its modern history. That is the note, important–I don’t know if it’s depressing or exhilarating. People do resist.

But I’ve been talking to Clayton Dube, who is the, here at USC, the head of the U.S.-China Institute. I know, I’ve heard him speak a number of times, and he’s a really interesting and honest observer. And I think we have a very exciting program here. Want to thank the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, and particularly Sebastian Grubaugh, who is the engineer who brings these shows to us. Our producer is Josh Scheer. And we have a historian, Jim Mamer, who was once the social studies high school teacher of the year for the United States, who’s taking these broadcasts–we now have a podcast, we now have 170 or something of them–and putting them into a textbook. So hopefully, someone who doesn’t have access to Clayton Dube will be able to pull this up the next time China is big in the news, or these trade issues, or what happened with Hong Kong, and use this as a resource. So want to thank you for giving us your time, and hopefully this will help with education. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.