All Politics Are Spiritual: An Interview with Marianne Williamson

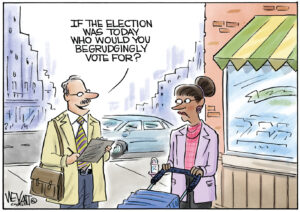

"Whether the DNC is ready to admit it or not," the two-time candidate says, " ...the rumblings underneath the surface shall not be silenced." Marianne Williamson speaks to the crowd as she launches her 2024 presidential campaign in Washington, Saturday, March 4, 2023. (Photo: Jose Luis Magana/AP)

Marianne Williamson speaks to the crowd as she launches her 2024 presidential campaign in Washington, Saturday, March 4, 2023. (Photo: Jose Luis Magana/AP)

Marianne Williamson is the only candidate for the Democratic nomination who cites Alan Watts and Ram Dass as formative influences next to Martin Luther King Jr. and the Berrigan Brothers. Since the late 1970s, she has worked as a politically active spiritual counselor and writer, penning more than a dozen books, including several New York Times bestsellers and 2019’s The Politics of Love: A Handbook for a New American Revolution, the clearest statement of her worldview that combines traditional left-wing politics and nondenominational spirituality.

Williamson first ran for office in 2014 as an Independent in the race to represent California’s 33rd congressional district. As a candidate in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, she gained notice for her performance during the second televised debate, after which she became a trending subject on Google search and a target of the DNC. Truthdig spoke with Williamson by phone last week during a break from her family obligations in London, where she was celebrating the birth of her first grandchild. This is the first in a series of interviews with Joe Biden’s challengers for the 2024 Democratic nomination for president. The transcript has been edited slightly for clarity and length.

Truthdig: During the Cold War, it was common to start presidential candidate interviews with foreign policy. Since the situation in Ukraine involves Cold War stakes and risks, let’s begin there. How do you understand Washington’s role and what would a Williamson administration be doing differently?

Marianne Williamson: It’s naive and foolish to think United States meddling had nothing to do with this. Of course, it did. Everything from breaking our promises about how far east NATO would go, to the Aegis missiles in Poland. However, I am not of the belief that any of that justifies the brutal imperialism of Vladimir Putin. It is a classic technique of the abuser to say, “You made me do it.” I am not naive about the U.S. war machine, the military industrial complex or the predatory imperialistic tendencies of that machinery. But neither do I underestimate or fail to reject the imperialism of Vladimir Putin. You have to walk and chew gum at the same time on this one. I think that the difference between myself and many who see it [as merely] “a proxy war” is that I recognize a lot of agency on the part of the Ukrainian people. When you look at the way the Ukrainians are fighting —the spirit, the passion and the sacrifice — you don’t fight that way if you’re nothing but an agent for the U.S. government. They’re fighting for their country. I believe that you can recognize the meddling of the U.S. government and at the same time argue that sovereignty matters. Both can be true.

Truthdig: Should Washington be using its influence to push for a settlement?

Marianne Williamson: Clearly there has to be a negotiated settlement. It’s the only possibility. Denmark has offered to host a summit and has correctly said that it makes no sense if it only involves Ukraine and its allies. In order for the summit to matter, it would have to include China, it would have to include India, it would have to include Brazil. It’s a multipolar world.

Truthdig: International relations is generally considered the most hard-headed policy realm, where it’s considered “unserious” to apply the kind of moral and spiritual framework that is the hallmark of your campaign. But it wasn’’t that long ago that people like Jonathan Schell found a large and receptive audience for the idea that security policy in the nuclear age was the defining moral issue of our time.

Marianne Williamson: The current economic system and paradigm wishes to divorce moral consideration from any public policy, domestic or international. That’s not hard-headed; that’s sociopathic. Franklin Roosevelt wrote that we have to do more than end wars, we must end the beginnings of all wars. That’s why he was envisioning, at the time of his death, the establishment of the United Nations. Then of course, his wife, his widow would be our first [UN] ambassador. The world was completely shocked when, a few decades after World War I, they were back at it again. They were hoping they were establishing a post-World War II order that would prevent some of the horror that we’re seeing now. John F. Kennedy said, “If we don’t end war, war will end us.”

Truthdig: Your foreign platform includes the creation of a U.S. Department of Peace, an idea most recently championed in Washington by Dennis Kucinich.

Marianne Williamson: The Department of Peace is the idea that we must proactively create conditions that will establish greater probability of peace. That means humanitarian efforts, and it means justice, in the absence of which violence and conflict are almost inevitable.

Truthdig: A major theme of your writing and politics is the “over-secularization” of public life and the disappearance of the idea of public morality. It’s a testament to the critique that a lot of younger voters wouldn’t even understand the concepts outside of the way they are used by the Christian right. They grew up without much exposure to the ideas of the old communitarian and religious lefts.

Marianne Williamson: When you talk about it being a distant memory, it’s not that distant to me. When I was growing up, the protests against the Vietnam War, the voices of William Sloane Coffin, the Barragan brothers — there was a sense of moral conviction expressed by the Catholics and the Jews in a very powerful way. On social justice issues, you could always count on the Jews and you could always count on the Catholics. Then they became, more than not, one-issue groups. Catholics became focused on abortion, and Jews on Israel. When I was growing up, the right side of the political spectrum focused on issues of private morality, and the left side of the political spectrum focused on issues of public morality, [including] poverty. Poverty is a moral issue. The preemptive invasion of a country that has done nothing to you is a moral issue.

Truthdig: Is the revival of this language and sensibility relevant to fully addressing the destruction of the biosphere? In Washington today, environmental issues, including climate change, are treated as technical matters — a question of emissions numbers, subsidies for breakthrough tech, incentives. The last president who tried to step back and frame the environment as a moral and even spiritual issue was Jimmy Carter. But aside from inviting E.F. Schumacher for tea at the Oval Office, he didn’t really try all that hard to get Americans to question the ideology of endless growth, or the American dream as a fantasy of consumption.

Marianne Williamson: How we are treating the planet, the lack of reverence, is a moral issue. How we treat animals is a moral issue. If your politics is only transactional, if it’s only about CO2 emissions, and never about reverence towards the Earth, then you’re stuck in a transactional political model that does not work. Dr. King was a Baptist preacher. Bobby Kennedy Sr. talked about how we were fighting for the soul of America. Many of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement were Quakers. A lot of the abolitionist movement, the white abolitionist movement, emerged from the early Evangelical churches in New Hampshire. You look at the larger historical trajectory of social justice movements in the United States and you see how often and how deeply they emerge from religious circles. Today, the politics of organized religious institutions, such as the Christian right, clearly has less to do with spiritual principle and more to do with ideology. But that does not mean that people don’t recognize that something is wrong at the center of things. The mindset of one century is always different than the last. The 20th century mindset was very mechanistic. It was based on a ton of Newtonian models: the world is a big machine. If you don’t like what’s happening, you tweak pieces of the machine. There is a British physicist named James Jeans, and he said a few years ago, “It turns out that the world is not one big machine, it’s one big thought.”

The 21st century paradigm mindset is much more holistic, much more whole person. In fact, everything we’re talking about here, bringing back spirituality, is the recognition that the mind divorced from moral principle is dangerous. Sociopathic behavior is deadly on a personal level and on a collective level. If you have an economic system in which short-term profit maximization for huge corporations is [put] before the health and the safety and the wellbeing of people, of animals, of the environment, of the life of the species, then you’ve got a huge problem on your hands. And that’s exactly what is confronting us now.

Truthdig: How do you make this holistic argument in a political culture dominated by the language of giving people slightly bigger slices of the pie, as opposed to questioning the purpose and meaning of the pie?

Marianne Williamson: You can look at political activism through a horizontal filter or through a vertical filter. If you’re thinking horizontally, you’re always tempted to dumb down your message in order to get more people to understand. This is the political act. It has no particular integrity to it. If you’re thinking vertically, you’re not thinking in terms of how to go wide. You’re thinking in terms of how to go deep. You’re thinking in terms, not of who to convince, but how to say it as well as you can. And the conviction with which you say it, because you mean it, because you are as deep as you can be within yourself, becomes a force multiplier. The majority of people did not wake up one day and say, “Let’s free the slaves.” The majority of people did not wake up one day and say, “Let’s give women the right to vote.” The majority of people did not wake up one day and say, “Let’s desegregate the American South.” I think about the difference between the provocateur, the activist and the politician. The provocateurs were the people who were passionate; everybody thought they were crazy. They’re necessary. They open the space. And then, because they open that space, the activist comes in next. The activist is someone who heard the message that was articulated by the provocateur. Once there are enough activists who have created more political possibility — that’s where the politician comes in. Lincoln is a perfect example. Lincoln was not an early anti-slavery provocateur. He was not an early anti-slavery activist. Though he did say early in his career, “If I ever get a chance to hit it, I’m going to hit it hard.”

Truthdig: Where do you fit into this schema of the provocateur, the activist and the politician?

Marianne Williamson: It’s interesting, isn’t it? I think we’re living at a time [where] everything is happening quickly, where it’s almost like all of us are provocateurs, all of us are activists and all of us are politicians. It’s the moment we’re living in. Bernie Sanders was clearly a provocateur. He was a politician, as well. But ultimately, his greatest success has been as a provocateur. He opened the space by opening the conversation, and creating the political field. A bunch of activists rushed in, and now the question is: Will we let a politician actually assume the political power that hasn’t yet been achieved?

Truthdig: Did Sanders inspire your entry into politics last cycle?

Marianne Williamson: I’ve always been inspired by him. Absolutely. As a matter of fact, in 2015, I hosted a conference in Los Angeles and invited him to be our main speaker. I think that was the first big public event where the subject was brought up about his running. I’ve been a huge Bernie Sanders fan and continue to be.

Truthdig: How do you see the overlap between your worldview and message and his, which is a little bit more focused on the material plane? He uses the language of morality, but it’s more grounded in concerns more associated with the traditional labor-left.

Marianne Williamson: He talks the way my father talks. In terms of socioeconomics, even ethnically, the way he speaks about politics — he’s like my dad or my uncles. Not that I’m not that much younger than him, but in terms of generational feel.

Truthdig: Even though it was the same decade, the early ’60s was very different from the late ’60s as a formative political period. I see you two as representing different ends of the decade. He’s more Port Huron Statement and sit-ins, the early ’60s, whereas you represent the post-counterculture.

Marianne Williamson: There’s also geography. I went to college in California. We would read Alan Watts and Ram Dass in the morning, and go to antiwar protests in the afternoon.

Truthdig: Were they your first political influences, or did they color a more traditional foundation?

Marianne Williamson: I was always interested in politics, always supported candidates — in high school, I fell in love with the campaign of Eugene McCarthy — but I felt that my own personal path of service and contribution would come within the realm of spiritual and personal transformation. What I began to see when I began speaking in the early ’80s, in 1983, was an almost ubiquitous despair. I had been involved in a lot of things like AIDS activism and peace work, up close and personal with people whose lives were in very rough shape. I began to see a level of despair that didn’t seem to be a kind of feature and not a bug of American life. And I realized it was because of, more often than not, bad public policy. You can say that your therapist, minister or rabbi is going to help you through a rough time, but if you still have to work three jobs…

Truthdig: Right. So this takes us into mental health, another defining concern of your career that carries over into the campaign. When did you start connecting the dots between the country’s mental health crisis and the unfolding of what you call the “evil flower” of Reagan-era economic policies, leading to the collapse of the middle-class and the upending of American politics and so much else.

Marianne Williamson: A mental health crisis is a symptom, not a cause, as much as pharmaceutical companies would like us to think differently. It is a symptom of a deeper level of despair. We have to ask ourselves, “Why?” It is ridiculous to underestimate the role that chronic economic anxiety plays in that. I began to see how many people did everything right and were [still] struggling to survive in the richest country in the world. I realized how different this was from when I was growing up and I thought, “What’s the difference?” Well, the difference was, when you were growing up, there was a vital, thriving middle class. In the 1970s, the average American worker had decent benefits, could afford a car, could afford a house, could afford a union vacation, could afford for one parent to stay home if they wanted to and could afford to send their kids to college.

I’ve done a lot of nonprofit work. [But] no amount of private charity can compensate for a basic lack of social justice. Politicians would say to me, “Miss Williamson, what do you think we ought to do about the mental health crisis?” I remember saying to a senator, “Stop driving people crazy. Maybe that will help.” Maybe give them health care. Maybe let them not be burdened by these huge college loans and worry all the time about whether or not they can send their kids to college. Let them be able to own a home, get an education. It became very clear to me. I also realized that the system does not have a problem with my saying this in bestselling books. It will only inconvenience the system if you try to get in there.

Truthdig: Going back to the question of making these types of critiques in different communities, what is the response to your mental health crisis analysis in, say, Rust Belt Ohio, as opposed to wealthy liberal communities around Los Angeles?

Marianne Williamson: The work I’ve done professionally is much like an AA meeting. The homeless person is sitting next to the mogul, but as they say in AA, “You’re all just drunks in here.” My work has always been geared less to someone’s socioeconomic [status], or religious or gender or any other form of tribal identity, and more to a place where we live inside ourselves. That’s what I feel I’m speaking to, the American heart. And I do think that Americans have an instinctive understanding that this country matters. That’s what I’m seeking to speak to. We all need to take all these filters down from in front of our eyes. We’re not being served at this point. If you’re a Jewish American, Black American, gay American, Hindu American, transgender American — the word I’m interested in at the moment is “American.”

Truthdig: Have you noticed that your idea of a “politics of love” has gotten more difficult to convey as the tenor of politics has gotten angrier? Or can that be overcome in more personal settings that operate in another mode?

Marianne Williamson: Unfortunately, a lot of the people in those intimate settings have been influenced by the [media] fairy dust thrown in their eyes by people who do not want my message taken seriously, who for their own purposes have created the “wacky crystal lady” image. The woo-woo love lady caricature is a way of obstructing the deeper message of love. When you talk about the deeper message of love, who doesn’t hear that? Martin Luther King said that it’s time to inject a new dimension of love into the veins of human civilization. I don’t hear anybody criticizing Cornel West for using that language. Nobody criticizes Cory Booker for using that language.

Truthdig: You’re saying there’s a double standard.

Marianne Williamson: You can just print, “Ha-ha-ha-ha.”

Truthdig: Understood. Speaking of Cornel West, he just announced his candidacy in the Democratic primary. The two of you have a similar message in some ways.

Marianne Williamson: Democracy is a good thing. I think it’s significant and good that there are three anti-establishment campaigns making it clear, whether the DNC is ready to admit it or not, that the rumblings underneath the surface shall not be silenced. That they cannot keep the lid on the voice of rage and calls for change that are coming up. There’s a political earthquake that is only just beginning to happen in this country. The little lines in the earth are beginning to form. There is going to be change. We are living in revolutionary times, whether we like it or not. So, we have two choices here. Things are not going to remain the same. They are going to break one way or the other. They’re either going to break in the way of greater democracy and greater justice, or they are going to break in the direction of authoritarianism and dystopia. We cannot idle in neutral much longer.

Truthdig: The role of the current DNC is to maintain this idling at all costs. They went after you pretty hard after your successful second debate appearance in 2020, when everybody started Googling you.

Marianne Williamson: There’s a political media-industrial complex. It was obvious last time, and it’s obvious this time. But there’s a lot more independent media this time. And I also think people are hipper to the strategies of the establishment now. These are the days of the internet. People, particularly young people, are looking at independent media sources. If you have the money, you can do so much more — through videos, internet advertising, and all of that. I’m limited by my finances but hopefully those finances will expand. That’s how Bernie was ultimately able to create so much of his own media. What saddens me sometimes is how vulnerable people seem to be to the narratives that are spun by the establishment when they want to get someone out of the conversation.

There’s a term ‘contempt prior to investigation.‘ You want to know what my books say? Why don’t you read them? Instead of some anonymous tweet about what they say, why don’t you read them? We’re living in mean-spirited times and there’s something about social media that gives people sometimes permission to indulge their least charitable impulses. You add a good dose of misogyny to that, and it can be hard.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.