A Unique Face of Evil

“Himmler was the complete opposite of a faceless functionary,” Peter Longerich writes in “Heinrich Himmler.” “The position he built up over the years can instead be described as an extreme example of the almost total personalization of political power.”

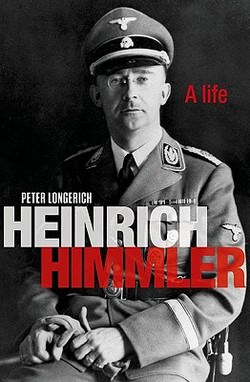

“Heinrich Himmler”

A book by Peter Longerich

This biography of one of the most evil creatures ever to walk the earth is thoughtful and perceptive, stupendously long and almost unimaginably exhausting. The first names that come to mind when the subject of 20th-century evil arises are those of the ungodly trio — Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung — but surely that of Heinrich Himmler belongs among them. Utterly devoid of courage, decency or genuine human feeling, he caused through his manipulation of the Nazi police bureaucracy the deaths of uncountable millions of people, almost all of them innocents, and when it was all over he died a craven death.

Himself a native German, born in 1955, Peter Longerich is a professor of modern German history at Royal Holloway University of London and a leading scholar of the Holocaust. That he spent as many years with Himmler as were necessary to the research and writing of this massive book suggests that he is a man with a strong stomach. Indeed there are many times in his “Heinrich Himmler” when the reader needs one as well, for the record of Himmler’s depredations is long, violent and bloody, and Longerich does not shrink from setting forth the details, as indeed he should not if he is to give us the full measure of the man.

At the outset Longerich asks: “How could such a banal personality attain such a historically unique position of power? How could the son of a prosperous Bavarian Catholic public servant become the organizer of a system of mass murder spanning the whole of Europe?” To address these questions, neither of which can be answered conclusively, Longerich has gone “beyond the established pattern of political biography and (taken) into account quite literally the whole of Himmler’s life in its separate stages and its various spheres of activity.” He argues that the crimes committed by the German police state in its various manifestations — among them the SS, its intelligence operation the SD and its military arm the Waffen-SS — were all Himmler’s crimes, because “he to all intents and purposes united in his own person all the instruments of violence belonging to the Nazi state.”

Thus this book is less a biography as the term is commonly understood than a history of the organizations that Himmler created in order to terrorize the citizens of his own country, the Jews of Europe, and Europe itself. “Himmler was the complete opposite of a faceless functionary or bureaucrat, interchangeable with any other,” Longerich writes. “The position he built up over the years can instead be described as an extreme example of the almost total personalization of political power.” Therefore it is necessary, Longerich convincingly argues, not merely to portray Himmler the man but also the institutions he created in his own image.

Himmler was born in 1900 into a respectable and almost entirely conventional Munich family. His father was a schoolteacher, his mother a homemaker. He was “the middle son, trapped between the model of the superior big brother and the solicitous care focused on” the youngest brother. He “had a sickly constitution, he was frequently unwell, and his whole appearance was delicate.” From an early age he was fascinated by “everything connected with war and the military,” and like countless other German boys of his generation he was deeply embittered by the peace imposed on his country in the Treaty of Versailles. He was in military uniform at the end of World War I but never saw action, which left him permanently resentful even though there is not a shred of evidence to suggest that he would have been a competent military officer, much less a brilliant or brave one.

|

To see long excerpts from “Heinrich Himmler” at Google Books, click here. |

“Nothing in Himmler’s childhood and youth,” Longerich writes, “would suggest that someone with clearly abnormal characteristics was growing up there.” He became obsessed early on, though, with “the soldierly world,” with its precepts of “sobriety, distance, severity, objectivity, but also order and regulations,” and its relegation of women to subordinate and supporting roles. “It was only much later,” Longerich says, “that he discerned ‘homosexual dangers’ in this way of life, with its protective cocoon of male solidarity and its self-imposed celibacy, and this was a disturbing insight that strengthened his latent homophobia.”

True enough, but Longerich does not explore the possibility that Himmler’s homophobia may well have been an outward defense against inner fears of his own homosexuality. From Hitler on down this was a pattern among the males of Nazi Germany. Himmler’s complex, ambiguous relationships with and feelings about women — he had a passionless marriage and, much later, an affair with his private secretary about which little is known except that “the couple cannot have seen much of each other, and they cannot possibly have lived together” — suggest that his sexual self-confidence was shaky and his true sexual identity uncertain. The possibility that the extreme violence he actively promoted in the organizations under his command was an expression of inner rage cannot, it seems to me, be discounted. After being mustered out of the armed services at the end of the war, Himmler drifted about, studying agriculture for a time before finally making his way into the radical right that was organizing alienated Germans in the early 1920s. He became “a Nazi agitator in provincial Lower Bavaria” and then, in the summer of 1924, “took the fateful decision to adopt the role of political activist and the true purpose of his life.” He became deputy Reich Propaganda Chief and then, in 1927, was given command of the SS (Schutzstafflen), “a very small formation” that essentially served as protection for Hitler and others. Longerich says this promotion “was almost certainly largely due to the fact that he organized meetings for prominent party speakers.”

Whatever the explanation for it, Himmler’s move to the SS surely had vastly greater repercussions than Hitler or anyone else could have anticipated. He proved, whatever his manifold shortcomings, something of a bureaucratic genius. He “knew how to combine ambitious ideological notions with a sure instinct for power,” and he negotiated his way through the Nazi leadership structure with extraordinary agility. He quickly built the SS into a massive organization, neutralized the leadership of the competing SA (stormtroopers), established the SD intelligence unit and by the autumn of 1935 “had secured control over the whole of the German police.” He “was able to succeed in pushing through his policy of establishing a uniform and permanent terror system that was outside the law and covered the whole of the Reich.”

The titles he held between 1927 and the end of the war nearly two decades later leave no doubt as to his power: Reichsfhrer-SS, Chief of the German police, Reich Commissar for the Consolidation of the Ethnic German Nation, Reich Minister of the Interior and Commander of the Reserve Army. His leadership style was, to put it charitably, peculiar. As a young man he had revealed an “obsession with interfering in other people’s private affairs and (an) almost voyeuristic interest in collecting details about their lives,” and these fixations stayed with him for the rest of his life. He was a compulsive meddler. He “saw himself primarily as the educator of his men” and interfered in virtually every aspect of their lives: “their appearance, their economic circumstances, their relationship to alcohol, their health, and … marriage and family planning.” Longerich writes:

“Himmler carried over his personal beliefs to an astonishing extent into the organization he headed; leading the SS was not for him simply a political office, it was a part of who he was. The task he had set himself in life was to create a strong internal organization for the SS, to extend it and to guarantee its future through his Germanic utopia. By working tenaciously to fulfill the tasks Hitler had entrusted to him, and by linking them adroitly, Himmler built up a unique position of power, which he shaped in line with his own idiosyncratic ideas.”

Those “ideas” often bordered on lunacy. Himmler was heavily into the occult, mythology, astrology, reincarnation and heaven knows what else, though he “never clearly expounded it as a coherent whole.” He often inhabited a fantasy world, and by the end of the war he may well have been insane, a possibility that Longerich declines to explore, no doubt for the entirely sensible reason that no firm evidence exists. Surely, though, all these nutty ideas heightened his obsessive nature, which went into overdrive when the time came for him to preside over “a campaign of racial annihilation of incalculable proportions.”

The details of that campaign are all too familiar. As mentioned above, this makes for exhausting reading, not to mention depressing and in the end heartbreaking. Even as the Nazis’ defeat loomed beyond a doubt, Himmler pursued the slaughter relentlessly: “The nearer the Third Reich came to its downfall, the more Himmler stepped up the use of terror in the occupied territories.” As Max Hastings and others have pointed out, German men and arms that could have been used to defend the homeland were instead used by Himmler for the slaughter of others, mostly civilians. As Allied forces neared the death camps that Himmler had so assiduously (one is tempted to say lovingly) built and presided over, he made a few feeble attempts to cover over what had been done there, but it was too late. When he was captured and interrogated in May 1945, he cheated justice by biting into a capsule of cyanide hidden in his mouth. True to himself to the end, he took the coward’s way out.

Jonathan Yardley can be reached at yardleyj(at)washpost.com. © 2012, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.