Film About Boxer Chuck Wepner Spotlights the Coalescence of Sports, Race and Politics

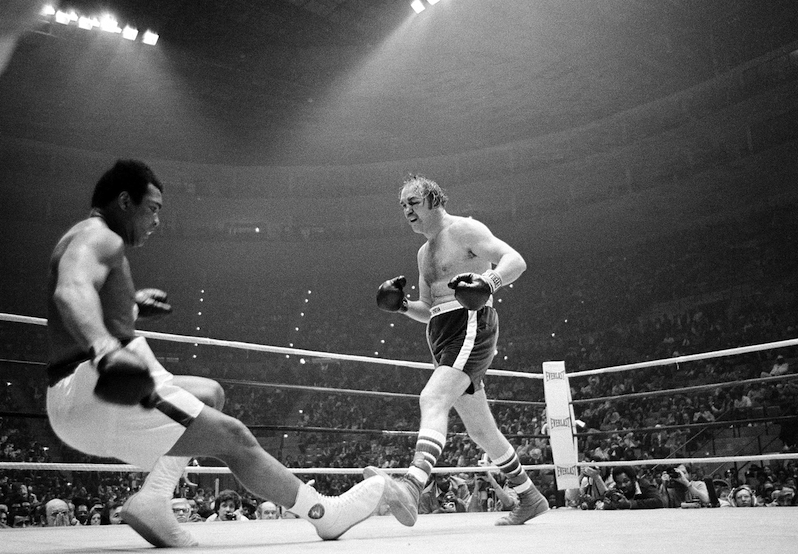

The heavyweight underdog—who almost went the distance against Muhammad Ali—gets his own cinematic treatment in the film "Chuck," after being the inspiration for Sylvester Stallone’s “Rocky” character. Chuck Wepner, right, fought defending heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali on March 24, 1975, at the Richfield Coliseum in Cleveland. Ali went down in the ninth round of the title bout but won a technical knockout in the 15th round to retain his title. (AP)

Chuck Wepner, right, fought defending heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali on March 24, 1975, at the Richfield Coliseum in Cleveland. Ali went down in the ninth round of the title bout but won a technical knockout in the 15th round to retain his title. (AP)

Chuck Wepner, right, fought defending heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali on March 24, 1975, at the Richfield Coliseum in Cleveland. Ali went down in the ninth round of the title bout but won a technical knockout in the 15th round to retain his title. (AP)

Sometime in the early 1970s—I can’t remember exactly when because when I ripped the column out of the Newark Star-Ledger I neglected to write down the date—Jerry Izenberg wrote of heavyweight boxer Chuck Wepner: “You’re Chuck Wepner, and you are the heavyweight champion of New Jersey, and that is something. But you’ve been that for some time now, and you can’t eat it and you can’t spend it and you can’t take it to the bank. And the realization may be dawning on you that it doesn’t mean a damn thing.”

The heavyweight championship of New Jersey didn’t really mean much until March 24, 1975, when Wepner (who spent most of his daylight hours tending bar, selling liquor and collecting debts for a small-time Hoboken mobster) got into the ring with Muhammad Ali and fought for the biggest title in boxing.

Wepner made it clear beforehand that all he really wanted was to “go the distance”—is this story starting to sound a little familiar? And he very nearly did. The fight was stopped with just 19 seconds left because Wepner’s face couldn’t stay out of the way of Ali’s fists.

No matter. Fourteen rounds, 2 minutes and 41 seconds was enough to give “The Bayonne Bleeder”—a nickname which should indicate to you what caused most of his losses—boxing immortality, or what passes for boxing immortality in New Jersey.

Actually, that’s not entirely fair. New Jersey has produced some great fighters, including Mickey Walker, who won the welterweight and middleweight titles in the 1920s; Jim “Cinderella Man” Braddock, a 10-to-1 underdog who came off relief rolls when he won the heavyweight crown from Max Baer in 1935; and Paterson’s Ruben “Hurricane” Carter, whose career was ruined after being wrongfully convicted of murder and sent to prison for almost 20 years—as Bob Dylan reminded us, he “could-a been the champion of the world.”

In truth, measured by the standards of these guys, Chuck Wepner’s career barely merits a split decision. His career record was 35-14-2, and it’s the loss to Ali for which he’ll always be remembered.

In 1975, Donald Trump’s buddy Don King jumped on the fact that Wepner had won a couple of fights and also happened to be white. Those two things didn’t often occur in the heavyweight class then, or now. This was not lost on Ali, who knew that he would sell a lot more tickets fighting a white contender than a black one.

Wepner lived up to his nickname, bleeding profusely, but also displayed an astonishing amount of guts, making the fight far more competitive than anyone, including Ali and Wepner, believed it would be. In one astonishing moment, Wepner sent the champion to the canvas—though whether the knockdown was caused by a punch or Chuck stepping on Ali’s foot or a combination of both will always be debated.

Here’s the greatest moment of Chuck Wepner’s life.

None of this would have mattered much if a young, little-known actor from Philadelphia named Sylvester Stallone had not been watching. Stallone was quick to notice how avidly the crowd rooted for the underdog Wepner, though he chose to ignore the obvious, namely that most of the crowd was white.

Stallone parlayed Wepner’s big night into an entire career, which was only fair since the “Rocky” movies, in turn, practically became Wepner’s sole reason for lingering celebrity, a fact made amusingly clear in Philippe Falardeau’s film “Chuck.” (You may not think that’s much of a title, but consider the original title, “The Bleeder.”)

Falardeau—a Canadian filmmaker who has made “Monsieur Lazhar” (2011) and “The Good Lie” (2014) with Reese Witherspoon and Corey Stoll—has not made a boxing movie but a movie about a boxer.

Liev Schreiber, as Wepner, offers an in-depth portrait of a shallow man. His Chuck is an amiable slob who doesn’t seem to want much more out of life than to win a few fights, drink beer while in training, and occasionally cheat on his wife, played by Elisabeth Moss in an electric performance. Moss makes so much of her limited screen time that she overshadows the great Naomi Watts, who plays a bartender and becomes Wepner’s second wife.

Schreiber looks like a lug but moves with remarkable grace when his character has to, particularly in the ring scenes. Chuck is something of a self-pitying jerk. In “Raging Bull,” Robert De Niro fantasized himself as Marlon Brando’s Terry Malloy in “On the Waterfront,” but Schreiber’s Wepner imagines himself as a far less noble character, Anthony Quinn’s washed-up “Mountain” Rivera in Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (“You tell ’em Mountain Rivera was no bum. Mountain Rivera was almost heavyweight champeen of the world.”).

What proved to be the biggest event in Wepner’s life was not decking the champ or even (almost) going the distance but Stallone basing “Rocky” on Chuck’s life—not just the fight with Ali but his entire life, down to, and including, having been a strong-arm collector for neighborhood mobsters. Stallone comes off as an amiable exploiter in “Chuck,” going so far as to lift a real-life incident (Wepner being thrown out of the ring during an exhibition with the wrestler Andre the Giant) for “Rocky III,” released seven years after Wepner fought Ali.

What the movie doesn’t tell you is that in 2003, Wepner filed a lawsuit for compensation, alleging that Stallone had reneged on promises of recompense. The suit was settled out of court in 2006 for an undisclosed amount. “Chuck” does, though, show Wepner finally outgrowing his own obsession with Stallone and the movie persona that was created for him. In terms of maturity, this was probably a bigger victory for Chuck Wepner than if he had knocked Muhammad Ali out of the ring.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.