Cristina Nehring on What’s Wrong With the American Essay

One of our most trenchant critics takes a withering look at how contemporary essayists in a global world have gone increasingly, foolishly, local.

His gaze has been so worn by the procession

Of bars that he no longer sees.

— “Essaylamba.com,” Rainer Maria Rilke

The essay is in a bad way. It’s not because essayists have gotten stupider. It’s not because they’ve gotten sloppier. And it is certainly not because they’ve become less anthologized. More anthologies are published now than there have been in decades, indeed in centuries. The Best American Essays series, which began in 1986, has reached 20 volumes. The problem is that these series rot in basements — when they make it as far as that. I’ve found the run of American Essays in the basement of my local library, where they’ll sit — with zero date stamps — until released gratis one fine Sunday morning to a used bookstore that, in turn, will sell them for a buck to a college student who’ll place them next to his dorm bed and dump them in an end-of-semester clean-out. That is the fate of the essay today.

The Best American Essays 2007

By David Foster Wallace (Editor), Robert Atwan (Series Editor)

Houghton Mifflin, 336 pages

Is it our fault? Are we, as readers, responsible for the decline of the American essay? Have we become lazier, less interested, less educated? Attention spans, to be sure, have shortened. Gone are the days when people pored over periodicals at languorous length during transatlantic crossings. But this is not the reason why essay collections gather dust and why essayists so often count themselves “second-class citizens” (in the words of E.B. White). If the genre is neglected in our day it is first and foremost because its authors have lost their nerve. It is because essayists — and their editors, their anthologists and the taste-makers on whom they depend — have lost the courage to address large subjects in a large way.

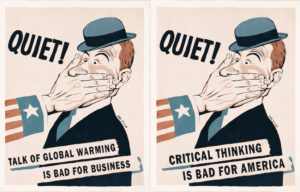

“The essayist is at his most profound when his intentions are most modest,” declares Joseph Epstein, the editor of “The Norton Book of Personal Essays” and the author of nearly two dozen books of autobiographical essays. The essay is a “miniaturist” genre, intones another anthologist; it is “in love with littleness.” Sound ingratiating? Sweet? Self-deprecating? It is. But it is also — as anyone who has spent time with these volumes knows — eye-crossingly dull. The essay that is considered “literature” in our day is not an ambitious or impassioned (if sometimes foolhardy) analysis of human nature. It is not an argument, or a polemic. It is not a gun-blazing attack on a social trend, a film, a book, or a library of books. Those sorts of pieces, sniff the anthologists, are mere journalism.

The essay they prefer has a distinctive tone, which Epstein has called “middle-aged.” I’m not an age-essentialist, but Epstein is, and what he means by “middle-aged” is clearly quiet. Slow-moving. Soft-hitting. Nostalgic. Self-satisfied. It’s the tone he perfects in his signature essay, “The Art of the Nap.” The tone Louis Menand espouses when he states — in the introduction to the 2004 BAE — that his preferred nonfiction “is the one that makes a lost time present.” The tone other BAE writers use when they reminisce rather aimlessly about their trout-fishing expeditions as a child; the drugstore on their block; the New Year’s party they spent watching television with extended family. “It’s only 11 o’clock,” Alan Lightman informs us in the keynote essay of the 2000 BAE, “but I am a morning person and I am already tired. I nod and sink into a chair. To wake myself up, I drink some tart apple cider. …” Hundreds of words later Mr. Lightman is still “half-sleeping against a wall” — and so are his readers. It was one lame night then, and it’s one lame night now. It does not improve in the retelling.

“Gentle” is how the 2006 guest editor, Lauren Slater, characterizes the essay she prefers. It must not, she tells us squarely, have “too much tooth.” Its author may be (and usually is) “narcissistic … but in a harmless way” (my italics). The essay’s “core,” she intones, should be “gentleness.” Given the choice to publish a provocative polemic or a navel-examining indulgence of private nostalgia, a haymaker from a literary heavyweight or an unbearably light appreciation of the author’s slippers, editors today will invariably choose the latter.

If the essays in these anthologies boast a distinctive (and distinctively dreary) tone, they also boast highly specific subject matters and — for all the editors’ sporadic salutes to individualism — startlingly homogenous author profiles. Reading the Best American Essays from 1986 to 2006, it’s tempting to create a composite portrait of the Preferred American Essayist: Educated at Harvard, he or she has spent significant time at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, written proposals for New York Public Library Fellowships (often lovingly paraphrased in the essays) and received medical attention at Sloan Kettering Hospital. Chances are good she’s a doting dog owner who has done such things as lace her pet’s dinner with “Prozac, Buspar, Elavil, Effexor, Xanax, and Clomicalm” (Cathleen Shine, 2005) or write gourmet cookbooks for his discerning palate (Susan Orlean, 2005 and 2006). More likely than not, he (if it is a he) has had a lifelong love affair with fishing or baseball, preferably both. An added bonus is to discover — or at least reassess — a Jewish ancestor in one’s family tree.Although Michel de Montaigne, who fathered the modern essay in the 16th century, wrote autobiographically (like the essayists who claim to be his followers today), his autobiography was always in the service of larger existential discoveries. He was forever on the lookout for life lessons. If he recounted the sauces he had for dinner and the stones that weighted his kidney, it was to find an element of truth that we could put in our pockets and carry away, that he could put in his own pocket. After all, Philosophy — which is what he thought he practiced in his essays, as had his idols, Seneca and Cicero, before him — is about “learning to live.” And here lies the problem with essayists today: not that they speak of themselves, but that they do so with no effort to make their experience relevant or useful to anyone else, with no effort to extract from it any generalizeable insight into the human condition. It is as though they were unthinking stenographers — “recording secretaries,” as indeed the most self-conscious 20th-century essayist, E.B. White, called them — pedantically taking down their own experience simply because it is their own.

The problem, of course, is not merely our essayists; it’s our culture. We have grown terribly — if somewhat hypocritically — weary of larger truths. The smarter and more intellectual we count ourselves, the more adamantly we insist that there is no such thing as truth, no such thing as general human experience, that everything is plural and relative and therefore undiscussable. Of course, everything is plural, everything is arguable, and there are limits to what we can know about other persons, other cultures, other genders. But there is also a limit to such humility; there is a point at which it becomes narcissism of a most myopic sort, a simple excuse to talk only about one’s own case, only about one’s own small area of specialization. Montaigne thought it the essayist’s duty to cross boundaries, to write not as a specialist (even in himself) but as a generalist, to speak out of turn, to assume, to presume, to provoke. “Where I have least knowledge,” said the blithe Montaigne, “there do I use my judgment most readily.” And how salutary the result; how enjoyable to read — and to spar with — Montaigne’s by turns outrageous and incisive conclusions about humankind. That everything is arguable goes right to the heart of the matter.

“The next best thing to a good sermon is a bad sermon,” said Montaigne’s follower and admirer, the first American essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In a good sermon we hear our own “discarded thoughts brought back to us by the trumpets of the last judgment,” in the words of Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance.” In a bad sermon we formulate those thoughts ourselves — through the practice of creative disagreement. If an author tells us “love is nothing but jealousy” and we disagree, it is far more likely we will come up with our own theory of love than if we hear a simple autobiographical account of the author’s life. It is hard to argue with someone’s childhood memory — and probably inadvisable. It is with ideas that we can argue, with ideas that we can engage. And this is what the essayist ought to offer: ideas.

In our own day the essay is an apologetic imitation of the short story. Like the short story, it tells a tale. Unlike the short story, it usually does not tell a very interesting tale — after all, this is nonfiction, so the bar for excitement is set lower. But speaking historically, the essay is not just a duller and tamer form of short fiction. It is in a different business altogether — and it should be. The work of the greatest essayists, past and present, is replete not with anecdotes, not with narratives, so much as with hypotheses; it is replete with bold theories, muscular maxims, portable inspiration. This is the very tradition that Montaigne himself drew upon. For much of his life Montaigne was known as “the French Seneca” — and not by accident: He modeled his essays after the thoughtful, feisty, pragmatic letters of that Roman writer and statesman. And Seneca, like Montaigne, like Francis Bacon, like Samuel Johnson, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, like Henry David Thoreau, was in the business of learning — and in the process of showing others — how to live and die. “Philosophy is good advice,” writes Seneca, before proceeding to mock the scholars of his own age who (precisely like those of ours) spend their time playing word games and toying with their navels. “I should like those subtle thinkers … to teach me this, what my duties are to a friend and to a man, rather than the number of senses in which the expression ‘friend’ is used. It makes one ashamed,” he declares, “that men of our advanced years should turn a thing as serious as this into a game.”

There was a feeling of urgency in Seneca’s prose — as there is in the prose of all the great essayists after him: “You are called in to help the unhappy,” he reminds his fellow intellectuals. “Where are you off to? The person you are engaging in word play with is in fear.” Seneca himself was in fear for much of his days; like every honest essayist-philosopher, he needed all the good advice he could give himself. After a life of political intrigue, success and persecution, he was asked to commit suicide by the emperor Nero, and he did — slowly slashing his wrists, then his ankles, then his knee interiors, before taking poison and ultimately climbing into a steam bath to drain his aged blood, which refused, stubbornly, to flow from his veins. He was, in some sense, prepared: His essays had proposed many ways to combat the fear of death, if not the pain of it: “A lamp,” he had wagered, is not “worse off when it [is] put out than it was before it was lit. … Wouldn’t you think a man a prize fool if he burst into tears because he didn’t live 1,000 years ago? A man is as much a fool for shedding tears because he isn’t going to exist 1,000 years from now.” A good point — and, it appears from Seneca’s own biography, a useful one.Seneca and Montaigne were middle-aged when they wrote their passionate essays; America’s greats — Emerson and Thoreau — were in their early 30s and younger. But none of them sounded “middle-aged” in the sense of Joseph Epstein. They all grappled with life, fought for solutions, fought for — yes — truths. We have no less need for truths and lessons and theories now than we did then, but today we leave the positing of these to televangelists and to tawdry self-help authors (“10 Ways to Be Happy”) and — indeed, as recent Atlantic essays suggest — to sports coaches (see “The Gym as Church,” December 2006). Our essayists have defected, leaving us on our own, with the impression that to traffic in boldness and generality is to be a blowhard or a huckster. The moderation of these triflers is immoderate, and it is only right that readers allow their work to rot in basements.

Today’s essayists need to be emboldened, and to embolden one another, to move away from timid autobiographical anecdote and to embrace — as their predecessors did — big theories, useful verities, daring pronouncements. We need to destigmatize generalization, aphorism and what used to be called wisdom. We must rehabilitate the notion of truth — however provisional it might be. As long as persons with intellectual aspirations are counted idiots for attempting to formulate a wider point, they will not do so, and even if they dared, most editors would not publish them and most critics would not praise them. Take the case of Laura Kipnis and her recent volume, “The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability.” While there is a great deal for which this book can be faulted, it has been attacked not for the dearth of its author’s talent so much as for the breadth of her ambition. It is the size of her topics that gives her highbrow critics pause: “What is dirt?” Kipnis asks, in a book in which she attempts to explore “the female psyche.” Her New York Times reviewer responds disdainfully, “Which raises the question: Who is Laura Kipnis?” In other words, how dare she ask such questions? Well, Seneca would have said, how dare she not? Life is short. “Assume authority. … It is a disgraceful thing that a man should derive wisdom solely from his notebook. … Utter yourself something that may be handed to posterity.” This is what Kipnis tries to do, and she should be saluted for it, not mocked. Her shortcomings lie elsewhere. But the territory she marks out for herself and the boldness with which she sprints into it are cause for gratitude. It is what all essayists should do.

In her introduction to 2005’s BAE, Susan Orlean (one of the best-connected editors in the series; her Web site announces that she may be hired for product endorsements) compares the contemporary essay to a cow . Not any old cow, mind you, but a plastic cow — a transparent cow — that Orlean has spotted in a store. “The Visible Cow,” she informs us, “offers an interesting and tangible analogue” to her choice of essays for 2005: “Just as each cow is individual, each of these essays is too.” As though the comparison were not yet stout enough, she goes on: “An essay can contain many thoughts and observations (those organs, those bones!) that might not seem to fit together but in the end lead to a satisfying whole — a cow.”

Let us mark this on our calendars as the official nadir of the American essay. The BAE editions of 2006 and ’07 are already slightly less bad. (There is no way they could have been worse.) Let us fight to make next year’s immeasurably better than both, than all. For the essay worth our time is nothing at all like a cow; it is nothing at all like a cud-chewing, conformist, slow-moving herd animal. If we must compare the essay to a beast, let us compare it rather to a wildcat. Let us give it back its tooth and nail, its fangs and claws; let us allow it to take risks, to pretend it has nine lives. Let us enfranchise it to disturb us. It is not Orlean’s incarcerated cow we need today, but Rilke’s panther breaking the bars of his cage.

Cristina Nehring writes regularly for several publications, including The Atlantic, Harper’s and the London Review of Books. She is the author of “A Vindication of Love: Reclaiming Romance for the 21st Century,” to be published by HarperCollins in 2008.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.