Carol Brightman on the 1960s

Three new memoirs by veterans of the New Left provide nuance and complexity to a tumultuous decade whose political and cultural legacy is still contested. Bonus points to those who can answer the question: Do you still need a Weatherman to know which way the wind blows?

The upheavals of the 1960s were the closest we came in the 20th century to radical change in the United States since the Great Depression. If, for some, the decade remains a media-hyped time of drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll, consider the following:

America fought a major war that was lost to an infinitely smaller power, and a growing anti-war movement at home kept military recruiters off college campuses, supported draft resistance, opposed, step by step, the escalation of troops and (contrary to popular mythology) eagerly welcomed a huge contingent of angry returning GIs who started their own movements. At a pivotal moment, after the Tet Offensive, the nation’s economic elite (known as the “Wise Men“) quietly counseled President Lyndon B. Johnson to withdraw from the upcoming presidential election and to halt the increase of troops in Vietnam, which had already reached 500,000.

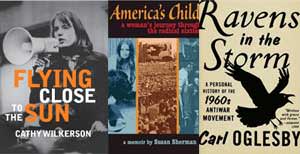

Flying Close to the Sun

By Cathy Wilkerson

Seven Stories Press, 422 pages

Ravens in the Storm

By Carl Oglesby

Scribner, 352 pages

America’s Child

By Susan Sherman

Curbstone Press, 239 pages

The Wise Men were not interested in peace but in security. When domestic opposition to the war grew more fierce in 1969 and 1970, President Nixon was compelled to withdraw U.S. troops and proceed toward “Vietnamization,” in the forlorn hope that a corrupt South Vietnamese military could win where Americans had failed, or, at the least, provide cover for Washington’s retreat. The focus shifted to the bargaining table in Paris, to a long, drawn-out contretemps between diplomats, which finally succeeded in quieting domestic opposition to the war.

The history of that opposition has still to be written in all its complexity. The publication of memoirs by three activists who played roles in that movement will help. Cathy Wilkerson — and to a lesser extent, Carl Oglesby — struggles to understand Weatherman’s intoxication with violence, how it grew out of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and also drew inspiration from Third World revolts. Wilkerson digs deeper into the social turf of Weatherman than has any previous insider account. Susan Sherman, for her part, writes about the volatile sexual politics of the Lower East Side’s arts scene and provides a vivid snapshot of Cuba in 1967-1968. Each of them gives a different (though occasionally overlapping) picture of the times and throws those faraway events into sharper relief.

You’ll want to plunge right into Cathy Wilkerson’s “Flying Close to the Sun.” If you’re a ’60s survivor (as I am), you’ll know it’s the real thing. But wait a moment; give the present its due for it is, after all, a present that has rid itself of the past and is tapping its toes to the beat of a different drummer. Today, with a war that never ends, the prospect of recession deepening into depression, the dollar that wears no clothes — you will perhaps wonder why people talk of the vote, as if who’s elected will matter a whit to the fall we’re about to take. Wilkerson will help you remember another, less blinkered, time.

Take 1968, for starters. The “system,” as we called it, was not so different from our “analysis” of it. Still mostly a home-grown thing, it was comprehensible. The Vietnam War made no sense, but there was, many of us thought, an endpoint if more and more people fought against it, and after the May 1968 Tet Offensive it was obvious that the Viet Cong were winning. A month earlier, when Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered, blacks erupted in the cities; then two months after Robert Kennedy was killed in June, white kids hit the streets of Chicago, host to the tumultuous August 1968 Democratic convention. (What was less obvious were the murmurings deep inside the system of a cabal, whose members were not much older than we, with different dreams, and a future: the neocons.)

In April 1970 I returned with hundreds of others from cutting sugar cane in Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade to a country that had tilted once again. Soldiers patrolled airports and railroad stations. The month before, three Weathermen had blown themselves up while making bombs in Greenwich Village. That year, according to the American Council on Education, protests, mainly against the war, would number more than 9,000. A breakpoint was reached in April when Nixon widened the war in Indochina by invading Cambodia. And days later, with 30 percent of the country’s colleges on strike, the National Guard fired on protesting students at Kent State in Ohio, killing four, and state troopers killed two black students at Jackson State in Mississippi. “Wholly unorganized and utterly undirected, the revolutionary movement exists,” wrote journalist Andrew Kopkind, speaking of the larger unrest that now included several armed undergrounds, “not because the left is strong but because the center is weak.”

That was the secret. The “system” was weak. Today, the left is weak, and with all the buffoonery in White House and Congress, the global order is slipping. Power has shifted from oil-consuming states to producers; from West to East. Abu Dhabi pours billions back into Citigroup, but stocks still slide. U.S. military strength — the string of bases encircling Middle Eastern and Central Asian oil and roping in Russia and China, as well — has faltered in action. In Iraq and Afghanistan. Big-time.

“On the morning of March 6, 1970, in the subbasement of 18 West 11th Street … a piece of ordinary water pipe, filled with dynamite, nails, and an electric blasting cap, ignited by mistake.” Thus begins Cathy Wilkerson’s remarkably candid book, “Flying Close to the Sun,” about her life with Weatherman and what led to its emergence in 1969. The Greenwich Village townhouse lifted by a foot or two, shattering bricks and splintering wooden beams, then fell into a pit in which a ruptured gas main burst into flames. This was home to her father and stepmother, who were on vacation, due back that day. Wilkerson was ironing sheets, and “saw the glow, like an engorged sun rising up from a huge gaping hole between me and the front of the house.” She could open her eyes only by blinking, so the tears could rinse away the dust that grated under her lids like sandpaper.

Editor’s note: Ralph Schoenman, who is discussed on page 3 of this review, has written a response in the comments below.She called out for “Adam,” her comrade Terry Robbins’ nom de guerre, but he was one of the three bomb-makers working below (Ted Gold and Diana Oughten were the others), and they were dead. Kathy Boudin heard her and cried out. She was in the shower, but now there was no shower. Wilkerson reached her and they stumbled to a house across the street, were given clothes and then disappeared down a nearby subway entrance.

How had Wilkerson and the others come to this point? By her own account, it’s the “purity” of her commitment to political change that stands out, starting with civil rights organizing in Chester, Md., while at Swarthmore, and moving on to anti-war work. She quotes SDS President Paul Potter’s famous 1965 Washington speech: “The incredible war in Vietnam has provided the razor, the terrifying sharp cutting edge that has finally severed the last vestige of illusion that morality and democracy are the guiding principles of American foreign policy.” And his call for a social movement “for people who are willing to change their lives, who are willing to challenge the system,” not just “write petitions or letters of protest,” reaches her too. In 1966, when the old guard gave up the leadership to newer members, mostly from the Midwest, including Carl Oglesby, she moved to SDS headquarters in Chicago and started to work on the national newspaper, New Left Notes. She, like so many others, was ready to “make history.”

The middle chapters of “Flying Close to the Sun” are dense, loaded with information and names from the past: her work with Peter Henig on the Selective Service System, discussions with Oglesby about whether (as he said) the “revolutionary motive is not to construct a paradise but to destroy an inferno,” her involvement with the women’s movement in Washington, D.C., and her fascination with Regis Debray’s theory of foco groups and how they resembled small group actions called “guerrilla propaganda.” She moved from one political project to another, embracing “Gentle Thursdays,” when the Austin SDS urged members to talk to jocks and engineering students. She dropped acid with SDS leaders and felt her role as “an apprentice was changing into that of full participant and even, a little bit, into that of a leader.”

Wilkerson’s book is an intriguing mix of inside movement history and a character study of a woman beset with contradictions. The daughter of a senior vice president in charge of the international division of advertising giant Young & Rubicam, she survived an upper-middle-class adolescence in New Canaan, Conn., “by elevating suffering to a quasi-spiritual level.” Years later, listening to Weatherman Bill Ayres extol guns before the Days of Rage in Chicago in 1969, she first thought it absurd, then succumbed to a “desire to sacrifice [herself] wholly for the cause. The purity of total dedication scraped away many of the complexities of life and promised ultimate gratification.” Besides, she wanted to be on the best team, “the most sacrificing, the most uncompromising. …” But when she landed in Cook County Jail, the “leadership women” were bailed out immediately, while she, not being among them, languished for weeks, and wondered. Being accepted into Weatherman’s inner circle would elude her, despite her willingness to, as she writes, “manipulate [others] into adopting the organization’s current perspective … in order to protect my own standing.”

Looking for the saving grace in the townhouse bombing, Wilkerson insists that “even though our actions had been a failure, the intensity of our anger had at last been heard throughout the country. … We were in way over our heads. … But on this one thing, being a voice of outrage, we would be united until the war ended.” She thought of her conversation with Terry, about “growing into the role of being warriors. If we had just taken a little more time, I thought, if we had just slowed down.” “I had read Lenin,” she recalls, “who convinced me that we had to use whatever advantages we could in the fight for a better world. I knew that this reasoning had led to, or at least had not prevented, the hideous abuses of power carried out by Stalin. But, we knew better now, I thought. We would never do that.” But Terry, who was her lover, didn’t know if it took one stick of dynamite or 10 to blow down a door.

Shortly after the explosion, the remaining Weather leaders met on the West Coast. Everyone repudiated the debacle of the townhouse but one, who left. Repudiation, of course, meant eliminating just the nails, which turned the bombs into antipersonnel weapons (to be left at an officers’ dance at Fort Dix, the target). The bombings, sans nails, resumed almost immediately. On May 21, 1970, Weather leader Bernardine Dohrn issued “A Declaration of a State of War.” Not long afterward, New York’s police headquarters was struck, setting the tone for all the group’s subsequent bombings. In the bombings, a “device” was left in a hiding place, with a timer set for the middle of the night, and a warning call made to clear the building. Luckily, no one was ever seriously hurt. A statement tying the “symbolic” bombing to a political event, usually a black prison uprising, was issued but rarely published.

“Like most people,” she concludes, “I was corruptible; able to be seduced by power and everything that went with it” — including an intimate relationship with one of Weatherman’s more powerful men, Terry Robbins, something she hoped “to sort … out later.” By 1975, when the war ended, Weatherman began to scatter. Wilkerson lived underground, had a baby girl, moved to a black neighborhood and began to put herself together again. Like Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayres, who had two baby boys, she decided to surface. But while she got a year at Bedford Hills Correctional Association for possession of illegal explosives, the conspiracy charges against Dohrn and Ayres were dropped (in 1981) because of extreme government misconduct. Better lawyers, perhaps. Or the luck of the leaders.

“In the end,” Wilkerson concludes, “we would lose sight of the potentially resilient qualities of people and of our own movement, qualities like flexibility, compromise, forgiveness, creativity, intellectual rigor, and the valuing of each life as much as possible. … In many respects, our efforts were doomed to crash and burn.”

Wilkerson would eventually find a job teaching math in the New York City public schools — a job she would hold for the next 20 years. Carl Oglesby, who went from being a copywriter for Bendix, a Michigan-based defense contractor, to president of SDS in a month, is a more complicated piece of work. Married, with three kids, and already 30 when he joined SDS in 1965, he was also a budding playwright. He quickly emerged as a brilliant speechmaker and co-author (with Richard Schaull) of the valuable “Containment and Change,” published in 1967, which, ironically, gave Wilkerson her first doubts that massive social movements would be enough to successfully fight imperialism. In “Ravens in the Storm,” Oglesby revisits, without apology, his stump speech. “I am a republican democrat and at the same time, yes, a democratic republican. Or in brief … a radical centrist. This is not an oxymoron,” Oglesby insists. “Democracy without the rule of law is anarchy, just as republicanism without democracy is tyranny.” Go figure. America was fighting a war without a declaration of war, which was (and is) its wont. This was his favorite point.

His coverage of the protest years is dilatory, with the exception of two interesting trips he took abroad: one to Saigon in late 1965 and another to the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal in Stockholm in 1967. He went to South Vietnam with a small teach-in delegation and met with a group Oglesby calls “The Bourgeois Gentlemen of Saigon,” who were probably close to the Viet Cong. Their peace plan was nearly the same as the one adopted in 1975 — 3 million lives later. The delegates later watched B-52s attack VC positions around Tan Son Nhut airport from a hotel roof about a mile away. They met with a “subaltern” of Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky who regaled them with anti-war anecdotes. In Hue, Joe O’Neal, the chief of the American consulate, told them (and everyone else) that a Communist victory had already occurred. Half the Saigon government was Viet Cong, he said, and half of American aid ended up in Hanoi, and most of the rest in Swiss banks. “Screw it!” he exclaimed. “We tried our best. Let’s pack up and go home.” German members of the University of Hue’s medical faculty told Oglesby that O’Neal was suspected by locals to be the CIA’s chief of station.

Oglesby’s account of the Stockholm trip gives a vivid portrait of Ralph Schoenman, the American expatriate and Russell’s representative to the war crimes tribunal. Oglesby was a great admirer of Jean-Paul Sartre, who, together with Simone de Beauvoir and Vlado Dedijer, a World War II adjutant of Tito’s and a hero of the Yugoslav anti-Nazi resistance, presided over the tribunal. Schoenman represented Lord Russell, who remained a ghostly figure in Wales. Each day Schoenman announced: “Lord Russell says he expects the tribunal to find the United States guilty of genocide,” the subtext being that Russell was paying for the damn thing and didn’t want to be unhappy with the findings. Sartre, who disagreed, saw American attacks on population centers (in South Vietnam) as resulting from the fact that Viet Cong and North Vietnamese combat units often stationed themselves there. Besides, to call it genocide evoked memories of Hitler’s effort to exterminate the Jews, which was not what was happening in Vietnam, ugly as the war was. He wanted the evidence to speak for itself, and he let it be known that he thought Russell was pushing North Vietnam’s propaganda line.

“Lord Russell was unhappy to hear of the recent attacks upon him by certain tribunal members,” Schoenman said. “He is all the more distressed by these attacks in that they are occasioned by large differences within the tribunal on the issue of genocide.”

“No one has attacked Russell,” said David Dellinger, who was the tribunal’s American secretary and sometime peacemaker. “We simply disagree with him. … Why does he consider disagreement a personal attack?”

“That is for Lord Russell to say,” said Schoenman. “I would not presume to speak for him. I am here only to say that Lord Russell believes the United States guilty of genocide in Vietnam, and that he would be disappointed if the tribunal continues to attack him for this view — .”

“Premiere!” thundered Sartre. “Our findings will be significant only if they are supported by facts! Deuxieme! It is you who are under attack, Schoenman, not Lord Russell! Troisieme! You cannot both stand behind Lord Russell and put him in your pocket!”

Schoenman bowed his head slightly but kept his composure. “I will see that Lord Russell receives a faithful account of your statement.” It was not a “knockout,” as Oglesby puts it.

Sartre glared at Schoenman, then turned to de Beauvoir. She lowered her eyes and nodded briefly, and Sartre turned back to Schoenman. “Merci,” he said quietly, and the battle was over. Schoenman had upheld Russell’s line, which was some weird variation of Trotskyism and had reflected North Vietnam’s thinking not at all.

Early in 1967, I had gone on the second of the tribunal’s two fact-finding teams to North Vietnam, the only American and only woman. One night at the end of the month-long trip we were seated behind a screen at the Metropole Hotel in Hanoi, drinking and swapping stories. The North’s “Four Point Peace Proposal” had just been issued, and Schoenman, it was said, had stood up at a dinner with North Vietnamese leaders and rebuked them for thinking of peace. He raised his glass in a victory salute; no one responded.

“Ravens in the Storm” is good on confrontations, especially when they concern Oglesby. His feel for dialogue, which is re-created, rings mostly true. For example, there are a few run-ins with Bernardine Dohrn (“BD”), including an endless back-and-forth, rather convincing really, between the two of them over Dohrn’s reasons for excluding him from Weatherman’s sponsorship of the first Venceremos Brigade — even though the original idea, proposed when he was in Havana in 1969, was his. She never let him forget his early willingness to speak to corporate types or his liberalism. And while Oglesby insists he was no “pacifist,” he was increasingly troubled by the rise of Weatherman. Soon he would find himself on the outside looking in, no longer regarded as a trusted member of the leadership of the organization he’d worked so hard to build in its early years. It left him baffled and distraught.Leadership was an important tenet in SDS. Organizational, regional and sometimes chapter leaders were endowed with extraordinary powers, which had less to do with the values they had picked up from the rank-and-file membership than the ideas they shared with each other. The need for secrecy steadily grew out of this subtle distinction. As the gap between members and leaders grew greater, the secrecy about decisions being made at the top became more pronounced. Weatherman, for example, which arose from the collapse of SDS in 1969, didn’t hesitate to use secrecy about strategic planning to keep order in the ranks. The original ideals of “participatory democracy” as announced in SDS’ founding Port Huron Statement of 1962 had, by this time, become a casualty of the sectarian strife that split the organization and the Leninist ambitions of some of its most zealous activists. Oglesby, who refused to follow the Weatherman line, was, in this sense, no longer a leader of SDS. The issue of whether or not to embrace violence was at the heart of his disaffection from his former comrades.

Oglesby gives both sides of the argument against violence after the 1970 townhouse explosion, quoting radical filmmaker Robert Kramer (whose apocalyptic movie “Ice” was a fevered depiction of a fascist America which a persecuted radical urban guerrilla resistance seeks to overthrow) as saying: “We have to realize that the rulers of the American empire are not going to roll over and play dead in the face of the kind of moralistic entreaties that you seem to go for.” Oglesby retorts: “As a quick and dirty first estimate, I would say that [my view] is at least ten orders of magnitude more plausible than your pipe-bomb dreams.”

Daily events, however, kept the issue of violence in the air. Three days after the townhouse explosion came word that Ralph Featherstone and Che Payne, two field secretaries for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), were killed when a bomb exploded in their car. Then, on March 11, a large bomb blew out the side of a Maryland courthouse. And the next day, in the early morning hours, bombs exploded in three Manhattan skyscrapers housing the offices of Socony Mobil, IBM, and General Telephone and Electronics. A previously unknown group called “Revolutionary Force 9” gave the police a half hour’s notice to clear the buildings. Weatherman wasn’t responsible as it was still reeling from the self-inflicted disaster of the townhouse explosion. But this spate of bombings made it clear that the Weathermen weren’t alone in their rage and despair. Nor, clearly, were they alone in their willingness to violently resist the American imperium.

In the months that followed, the American public’s approval of Nixon’s handling of the war would drop from 64 to 46 percent; but Oglesby maintained his faith in the persuasive power of nonviolent tactics. “We started from nowhere five years ago,” he told Kramer, “and now almost half the American people are against the war.” They shared a commune in rural Vermont, where Kramer ran a firing range in the back fields. “Nixon cares what people think?” Kramer exploded. “Refusing to pick up the gun is the best possible way to make everything we’ve won so far meaningless.” And on and on it went, until Oglesby felt he had to leave. Even if the demonstrations against the war were attracting fewer and fewer people, he had faith in nothing else.

Oglesby’s view of the war’s ending is strange. Not Weatherman, or the broader movement whose nonviolence Weatherman scorned, and not outrage in Congress either; it was Watergate that did it, he maintains, beginning with the arrest of the burglars at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington on June 17, 1972, and ending with Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 8, 1974. SDS, he writes, no doubt “helped” set the stage for the final act, “but by that time it [the war] had already long since been carried from the field in a body bag, dead for as long as it had been alive.” This wording is unfortunate, as if Oglesby is standing centuries away from the war’s bitter carnage.

Susan Sherman’s “America’s Child” is a book in two parts. The first, which begins in Berkeley in the 1950s, reads like a string of clichés, broken by lines such as “I can’t imagine those years without them.” The second, which follows a trip to the Cultural Congress of Havana in 1967, reads very differently. In the first part, love happens, “sudden, unexpected, sure … a moment I knew instantly would remain recorded in my memory to the last detail.” And you’re nearly asleep when a 1961 visit home to Los Angeles arouses you. Sherman’s stepfather, who had once been the Hollywood agent for Abbott and Costello, is reading about a Berkeley demonstration against the HUAC hearings, drops his paper and announces that if she was involved in it (she was) he would be the first to turn her in to the FBI.

Her brief account of the history of her family — poor Jews who left her mother with a hunger for lying to herself — is horrific. The mother finds herself married to her second husband, the stepfather, fleeing the impoverished suffocations of Philadelphia to the beckoning glamour of Beverly Hills, hobnobbing with movie stars, and then, when it all goes south, sliding downhill, to a tiny run-down apartment on the wrong side of Sunset Boulevard, living with a now bitter old man, a box of cigars and a few pieces of silver. The mother made a virtue of forgetfulness, and Sherman, to her credit, does not.

More love, this in the chapter called “Coming Out.” “Touching Sylvia’s face, her arms, tentatively … the passion growing from within, extending out through my fingers. …” We’re in New York now; it’s a humid July afternoon. “… [T]he touch of her breasts, her legs, reaching slowly, hesitantly, the curve behind her ear … as she reaches down, between my knees, my thighs, touching me as I touch her … moist, probing inward, searching. …” You get the idea.

In the early 1960s, when Sherman moves to the Lower East Side, she is unaware of the forces that drive her and the world around her. “I moved in a state of grace,” she says. She recalls the Deux Megots, the coffeehouse run by Mickey Ruskin, who later owned The Ninth Circle, then Max’s Kansas City, famous as a hangout for Andy Warhol. It was at the Deux Megots where she learns to write poetry. She is never sure how much she, or the others in her crowd, broke through “the cerebral fences that dictated even in that bohemian context what was expected in both our poems and our lives.” She believes that poetry and poets are supposed to be beyond gender and race, background and religion — “outside of self and time.” It would take a new kind of experience, far from home, to help her understand that she would have to enter these realms before she could move beyond them. Meanwhile, Sherman starts reading her love poems about a woman to a larger audience. Grace Paley and Robert Nichols, among others, encourage her. Much later, in 1975, Denise Levertov, who had disapproved of her (gay) images, would publish Sherman’s “Amerika” in the American Poetry Review.

In the next couple of years Sherman finishes a master’s thesis in philosophy, starts teaching at the Free University, works at the classified ad department of the Village Voice, and has a play reviewed. She also reviews plays for the Voice and is asked to review books and plays for a new magazine, which culminates in her becoming co-founder and editor of IKON. Between February and July 1967 her life and the contents of the magazine begin to radically change. Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale start the Black Panther Party in Oakland; Haight-Ashbury is in full swing; draft resistance gains strength and momentum; and in New York, 10,000 people take part in the first Be-In in Central Park, and 400,000 march against the war from Central Park to the United Nations. Politics comes to her a little later than to Wilkerson, but she isn’t a political person, not yet.

The Vietnam War begins to escalate along with the anti-war movement. Almost every story, poem, article in the third issue of IKON is related to the conflict. Grace Paley’s “The Sad Story About The Six Boys About To Be Drafted In Brooklyn,” Robert Nichols’ “Vietnam Journal,” Jean-Paul Sartre’s Inaugural Address delivered at the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal (yes, the same), in which he proclaims that no matter what decisions the “trial” reaches, “the judges are everywhere; they are the peoples of the world, and in particular the American people.” Margaret Randall, living in Mexico, writes about the eighth anniversary of the Cuban Revolution, and Sherman reports on something called the Angry Arts Against the War.

These were not just pieces in a magazine, Sherman reflects. “Each represented an activity in which we were either directly or indirectly engaged.” Something similar happened with Viet-Report, the anti-war magazine I started in 1965. We began by running pieces by experts, then found that the experts couldn’t tell us what we needed to know and we had to research and write them ourselves; and then join teach-ins, give speeches, travel to North and South Vietnam, march, and march some more. When the war came home, we were involved in that, too. Our last issue, in the summer of 1968, was subtitled, pompously enough, “Colonialism and Liberation in America.”

The second part of Sherman’s memoir, “Cuba and After, 1968-1971,” reads like a different book. It’s no longer about herself but, at first, about Old Havana, Santeria (the Afro-Cuban religious tradition), the efforts to form a New Man (or “new human,” as Sherman says). Her roommate in Havana is the Spanish-speaking Margaret Randall, who seems to know everyone. Sitting one afternoon in the lobby of her hotel, Sherman begins talking to a young poet from North Vietnam. Upon hearing she is a poet from New York, he jumps up and returns with a dogeared book of poems, his favorite, Walt Whitman, and a poem he has written for a Cuban newspaper about Whitman and Vietnam.

When she and three members of SDS meet with a small delegation of Vietnamese, they are praised for standing up against the war, and for their bravery. They protest that compared to what the Vietnamese are going through nothing they’ve done is worth talking about. “No,” one of them responds. “You don’t understand. We have to fight. We have no choice. You don’t, yet you support us. Even against your own government. … You support us by choice.” Sherman understands “for the first time how important it was to organize from a people’s pride and not from anger or guilt.”

After she returns home, the art staff bolts from the magazine, her health begins to break down and the FBI initiates an investigation. The bookstore where IKON was produced has La Mama on one side and a transvestite nightclub that was rumored to be run by the Mob on the other. The doorman is a retired police sergeant, and Sherman and some co-workers chat with him and give him small gifts. No trouble there — that was how it worked in New York.

She writes Rene Vallejo, Fidel Castro’s personal physician, whom she had earlier befriended, and in December 1968 he asks her to come to Cuba again for a stay in the National Hospital. We never learn exactly what’s the matter with her, but after a month Vallejo declares her cured and promises a surprise meeting with “the prime minister.” One warm evening, she is picked up at nearly midnight by a uniformed guard in a jeep and taken to a huge stadium outside the city. Soldiers with submachine guns stand behind pillars. She is led into a gymnasium, where a dozen middle-aged men in make-shift shorts and tank-top uniforms are playing a desultory game of basketball. Hours go by. It is now well past 2 o’clock in the morning. Finally, Castro enters with Vallejo and is pointed in her direction. She notices his eyes, “radiating isolation.” She thanks him for her care and gives him some funny hospital details, which make him laugh.

During the conversation, Sherman mentions that “Vallejo had said to me that they expected reform [in Cuba] not revolution,” and that “they had great hopes if [John] Kennedy had lived that some accommodation could have been reached.” Given the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, this is interesting. He also remarks wistfully that “government and business could solve so many problems if only they gave an inch or two, but they wouldn’t even do that.” Those were the days.

Sherman returns to New York after a two-month tour of the island, grateful to Vallejo, who invites her back next year. But he would suffer a stroke on the basketball court, of all places, and died at 44. A tall man, taller than Fidel. Along with Celia Sanchez, Castro’s comrade in arms in the Sierra Maestra and later his secretary, Vallejo was, Sherman believes, the only person Fidel completely trusted.

This is not a thrilling book. It all happened so long ago, and Sherman fails, for the most part, to make it new. At the end, however, she observes that the 1960s was not an isolated era, “but part of an historical continuum of struggle and cultural regeneration, moving backwards … through the civil rights movement in the Fifties, progressive movements during the great depression, the labor movement, the first meeting of the NAACP in 1909 to untold heroic acts against slavery … to the revolutionary movement out of which this country was born.” It is an important thought, one to paste over your desk while writing. But, alas, none of these authors has kept it in mind.

It would have made a difference if Wilkerson, Oglesby and Sherman had moved back, at least once, from the personal stories that compel them to reflect on these earlier episodes of radical change in American history — for they are not alone, far from it. But by virtue of the kind of memoirs they’ve written, they’re still rooting about in the dense undergrowth of the 1960s and 1970s, throwing out this bit, keeping that part. They do not think about whether earlier political movements form a continuum going backward or forward, and, if forward, where they stand in the onrushing process to rid the world of American bellicosity and hubris.

In many ways, these three books are the memoirs of activists who have shed the carapace of their old organizational selves but are still at pains to understand who they were and what they’ve become. None of them renounce their earlier selves — except Wilkerson, a little — and Wilkerson is the only one who tries to make a connection with the future. She says it best: “When I look back on the early years of my life, the tremendous accomplishments, the ignorant and arrogant mistakes, and the losses, I ask, ‘For the sake of what?’

“For the sake of a future, I hope.”

Carol Brightman is the author of several books, including “Writing Dangerously: Mary McCarthy and Her World,” “Sweet Chaos: The Grateful Dead’s American Adventure” and, most recently, “Total Insecurity: The Myth of American Omnipotence.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.