Redrawing the Political Map

A little-noticed California proposition could limit the kind of partisan gerrymandering that Republicans and Democrats have used to influence elections around America for decades. But is that a good thing?

“I’m the majority leader, and I want more seats,” former U.S. House Republican Majority Leader Tom DeLay famously declared in 2003. DeLay got his seats — six more — by remapping Texas in the boldest gerrymander of modern American history.

Now, The Hammer’s legacy is in jeopardy. California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger successfully led the charge to pass California’s Proposition 11, which limits the kind of partisan gerrymandering that DeLay, and his Democratic counterparts, used to influence elections around America for decades.

In the past, California has been a national trailblazer when it has enacted broadly felt sentiments. Proposition 13 is the most famous such example, that being the property tax cap of 1978 that set off an anti-tax revolution across the country. Not every California proposition becomes a national model, but “the redistricting law in California is interesting,” says attorney and redistricting expert Sam Hirsh, “because it’s such a big and often trendsetting state.” He would know. A former campaign manager and Capitol Hill aide, Hirsh represented the Democratic Party’s national redistricting project in 2000, and argued before the Supreme Court against DeLay’s Texas map.

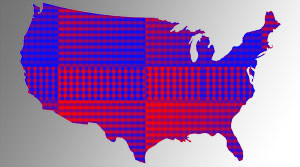

Gerrymandering is the process of drawing electoral districts so that one political party can maximize its number of seats in a given legislature. Typically, this creative cartography takes place in each state after the decennial census. Both congressional and state legislative districts are redrawn at those times.

The party in control of a legislature typically takes advantage of map-making. For example, a Democratic legislature will draw districts that spread out Republican voters, so that each district has more Democrats than Republicans. This doesn’t work for every district in a state, so the map-makers, in order to ensure a Democratic majority, end up settling for many districts that are safely Democratic and a few that are safely Republican.

The above scenario is precisely what has happened in California. In fact, the districts are so safe that in the 2004 election, when 153 seats were up for grabs in California’s congressional delegation and state Legislature, not one district changed parties. When a state has districts so strongly Democratic or Republican, the party primary becomes the venue for competition. The way to win party primaries is to tack far to the left or far to the right, and this pushes the candidates who win these primaries farther toward one end of the political spectrum.

That abstract problem became a jolting reality this week in the state capital of Sacramento. “Without immediate action, our state is headed for a fiscal disaster,” Schwarzenegger told reporters. The Governator is not lying: Health care providers who rely on state payments have almost gone out of business recently because the state’s budget was so late California nearly had to stop paying bills. Gerrymandering is at the heart of the problem: Far left and far right legislators can’t compromise on the ideological hot buttons of raising taxes or cutting spending, so the state can’t plug its massive budget hole.

Around the nation, state leaders are watching California’s hyper-gerrymandered Legislature flail. If the Legislature functions much better once it is redistricted, California will exemplify a remarkable success story for nonpartisan districting. To be sure, a handful of states already have nonpartisan districts, but California’s national spotlight, and its dire situation, may make it the trendsetter.

So what would happen? If California does blaze a trail and redistricting catches on, how would a fairly districted America look? “No one has made that map,” admits Gerry Hebert, executive director of Americans for Redistricting Reform. Hebert was an attorney for the Democratic Party of Texas during DeLay’s 2003 redistricting maneuvers.

No one knows for sure what would happen if, for example, America had 400 competitive congressional elections in a single election cycle. A few experts even argue that nonpartisan redistricting wouldn’t produce many more competitive elections. For example, Alan Abramowitz of Emory University argues that gerrymandering doesn’t make a big difference. Abramowitz asserts that the biggest decreases in electoral competition happen between redistricting cycles, largely because of complex demographic shifts.

It is almost certain, though, that comprehensive nonpartisan redistricting would lead to major changes in the partisan makeups of some states’ congressional delegations and legislatures. DeLay’s heavily gerrymandered Texas, for example, would see a dramatic change. Hebert points to Florida as another state where a nonpartisan map would yield a big partisan swing. The Sunshine State is politically moderate, but Republican gerrymanders have led to two-thirds control of the Legislature. Undoing that gerrymander would mean a significant partisan rebalancing. Examples like Texas, Florida and California suggest that even a few states ending gerrymandering would make a meaningful difference in the makeup of Congress and state governments. The end of gerrymandering could also affect legislators even if it didn’t replace them: Hard-core partisans are often pushed toward the center by competitive elections, even if they win.

With California leading the way, there are myriad reasons to foresee state-level success against gerrymandering in the coming years. Hebert points to states with an initiative process, “because self-interested legislators aren’t likely to give up power.” Florida and Ohio, like California, have the initiative process. A poorly structured ballot initiative for redistricting failed in Ohio, and a similar effort recently failed in Florida as well. But Florida political operatives may try again to pass a redistricting initiative in 2010. Moreover, operatives who run anti-gerrymandering ballot initiatives learn from each effort: “The California efforts succeeded because they included interest groups like minorities groups concerned about losing legislative representation,” says Hebert. He expects future efforts to replicate the tactic. Florida and perhaps Minnesota are the only states with strong chances to pass reforms in the next several years. But Hebert sees an advantage on the horizon: “2011 will create some really bad examples [of gerrymanders], and we’ll have the opportunity to create some national buzz [against them].” Shortly thereafter, the California example will just be starting to prove to be a success or a failure, so it will be particularly salient.

Michael McDonald, a professor at George Mason University, doesn’t believe California will catalyze state action. But he sees strong possibilities for redistricting coming from the federal government. McDonald notes that during the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama pledged to “encourage states to form” independent redistricting commissions. “Obama has some background in election law,” said McDonald. “We could see Obama getting involved in election reform.”

Federal action could take several forms. McDonald and Hebert both believe the president-elect may use his bully pulpit to call for nonpartisan districts. Both also point out that Obama’s will be the first Democrat-run Justice Department to preside over a post-census redistricting since Harry Truman was president. McDonald expects to see more strict enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, which protects minority districts and could be interpreted to disallow some gerrymanders. Due to a history of racially sensitive redistricting, all or part of 16 states are required to submit election district maps to the Justice Department for approval. Justice Department rulings on the maps of those 16 states have the potential to limit partisan cartography.

McDonald also sees possibilities for reform from Congress. While it has become a tradition for Congress to ignore the anti-gerrymandering bill perennially introduced by Rep. John Tanner (D-Tenn.), McDonald believes the bill could gain traction if Obama brings attention to the issue. However, others are skeptical that Tanner’s bill will go anywhere. The House Judiciary Committee hasn’t held a hearing on gerrymandering in years. Any such hearing is likely to take place in the subcommittee on the Constitution. That subcommittee is chaired by New York Democrat Jerry Nadler, and while Nadler’s press secretary “would agree that gerrymandering is a problem,” that concern hasn’t amounted to action. Wrangling the committee to move would probably require Obama to expend precious political capital.

State action would be piecemeal, and congressional action seems unlikely. A Supreme Court move, though, could have a sweeping effect. And “it’s possible,” says Sam Hirsch, the attorney who argued against DeLay’s district map in the Texas case.

If swinging the Supreme Court to action is possible, the hinge is Justice Anthony Kennedy. A Supreme Court majority requires five justices, and in the past, says Hirsch, “five justices have agreed that a strictly partisan gerrymander is unconstitutional.” The problem is that only four justices have agreed on the criteria for determining an unconstitutional gerrymander. Kennedy is the only justice who appears open to joining those four on a set of criteria. And if he does, a petitioner would still need to demonstrate that a particular partisan map distortion met those criteria. “I don’t see the case yet,” says Hirsch. “If I did, I’d take it. But the gerrymanders of 2011 and 2012 could produce that case.”

California could spur some state ballot initiative movements. The Obama administration could push for state or congressional action. The 2011 and 2012 gerrymanders may lead to increased demand for reform, and could even lead the Supreme Court to intervene. But is this what Americans really want?

Greater electoral competition sounds good. Yet more competitive elections mean that campaign money will be more important to more incumbents. So the greatest wellsprings of campaign money, including special interests, would be more powerful than ever.

Here is a (not very) hypothetical example. A particular member of Congress is a budget hawk with a safe seat. After a nonpartisan redistricting, the seat becomes competitive. Suddenly the incumbent, needing financial and political capital, has to cozy up to the biggest employer and political force in the district, which happens to be the defense contractor Lockheed Martin. All of a sudden, Lockheed’s federal budget-busting military aircraft sound like a great idea to the incumbent. Her ability to act as a budget hawk is gone. This is a more common scenario than one might think. Defense contractors intentionally spread out across the country in different districts for precisely this purpose — to influence as many representatives as possible. If more competitive elections cost more money, Lockheed, and politically powerful interests like it, will become even more influential.

What about the goal of bringing legislators toward ideological moderation with competitive general elections? Again, the notion sounds intriguing, but, Hebert says, when you “end up with more people in the middle, you end up with less people on the ends” of the political spectrum. Can America risk losing its few daring political voices? Regardless of whether one agrees with Ron Paul or Dennis Kucinich, their safe congressional seats allow them to challenge American political discourse in critical ways.

Experts disagree about California’s ripple effect. Many concur, though, that America now holds unprecedented potential for gerrymandering reform. After the 2011-2012 gerrymanders, that potential will build. Perhaps the greatest question is whether that momentum will be swept away in a storm of more urgent priorities.

Jeremiah Levine has managed and consulted on political campaigns at the federal, local, and state levels.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.