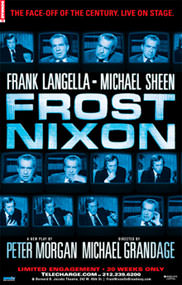

Allen Barra on ‘Frost/Nixon’

Frank Langella as Nixon in the new Ron Howard movie does his best, but no one did Nixon like Nixon.

Richard Nixon doesn’t deserve Frank Langella. Neither, for that matter, does Ron Howard. “Frost/Nixon,” adapted for the screen by Peter Morgan, who developed the stage play from James Reston Jr.’s book “The Conviction of Richard Nixon,” is directed in a blunt, conventional pseudo-documentary style that is unsuited to its subject. The film drags at first but eventually comes to life through the brilliance of its casting: Sam Rockwell as Reston; Toby Jones as Swifty Lazar, the agent who helped swing the deal that brought Nixon to national television in 1977; Michael Sheen as David Frost; and, best of all, Langella, whose intelligence and energy keep the film afloat and finally succeed in shining a penlight into the mind and dark heart of Richard Milhous Nixon.

“He was an immensely complicated man,” Reston told me last year in an interview for American Heritage, “and those very complications made him fascinating.” That’s the way Langella plays him, peeling away one layer after another until he sits revealed at the film’s end, a man who understands that his own name should have been at the top of his infamous enemies list.

Wherever he watches this film from, Richard Nixon will surely acknowledge that Langella has done him justice — and just as surely it must gall the man who wanted only All-American faces among his White House attendants to see his soul exposed by an actor with such Mediterranean features.

Peter Morgan (whose previous film scripts include “The Queen” and “The Last King of Scotland”) is merely the latest writer of imagination to dare a probe of Nixon’s psyche — Gore Vidal (“An Evening With Richard Nixon”), Philip Roth (“Our Gang”) and Norman Mailer (“Miami and the Siege of Chicago”) have all taken their turns at deciphering the 37th president.

Mailer, not entirely unsympathetic, probably came the closest to pinpointing Nixon’s Rosebud. At the 1968 Republican Convention, Mailer thought Nixon’s modesty to be “a product of a man who, at worst, had grown from a bad actor to a surpassingly good actor, or from an unpleasant self-made man — outrageously rewarded with luck — to a man who had risen and fallen and been able to rise again, and so conceivably had learned something about patience and the compassion of others.”

What Mailer, Vidal, Roth and others have never entirely explained was their fascination with a man they derided as shallow and unrelentingly prosaic. Yet, despite the derision of so many intellectuals — or perhaps, in some perverse way, because of it — Nixon has cast a long, dark shadow on American pop culture. Movies, for instance. With the possible exception of Abraham Lincoln, Nixon has been portrayed by more great actors than any other president. Just a partial list of movie and TV Nixons is eye-opening: In chronological order:

— Rip Torn in the 1979 CBS mini-series “Blind Ambition,” from the book by John Dean (and, it is rumored, though Dean has ever denied it, Taylor Branch). For many Nixon haters, Torn’s is the quintessential interpretation. He certainly gets the paranoia and megalomania right, but at times he overpowers the role: Could anyone so out-front nutsy have misled so many people for so long? Well, maybe. You can’t fool all the people all the time, but, as Nixon understood, you only need a majority. (Presidential movie trivia buffs will note that Martin Sheen, who plays John Dean, at one time or another played both John and Bobby Kennedy, as well as Josiah Bartlet on “The West Wing.”

— Philip Baker Hall in a one-man play about the final days before Nixon’s resignation, “Secret Honor” (1984), directed by Robert Altman. Hall doesn’t so much impersonate Nixon as caricature him — and nails it. There’s no attempt at balance here, but Altman knows that satire doesn’t have to be fair to be funny. Signature line: “They [the Republicans] will probably replace me with some dumb SOB who just looks good on TV.”

— Lane Smith, the late TV character actor in “The Final Days” (1989), adapted from Woodward and Bernstein’s book. A fine actor who never got the movie breaks, Smith may have been the best of all fictional Nixons, at least before Langella. No other performance drew us into an empathy with Nixon that stopped just short of sympathy. The uncanny casting coup of Theodore Bikel as Henry Kissinger helped raise “The Final Days” far above the usual made-for-TV fare.

— Jason Robards Jr. in “Washington Behind Closed Doors” (1992), the ABC TV movie made from a potboiler by yet another Nixon aide, John Erlichman. Probably because the book is a novel, the characters’ names had to be changed to protect the guilty. The script doesn’t allow Robards (as President Richard Monckton) to be much more than grumpy, and the production is stolen by Andy Griffith — yes, that Andy Griffith, TV father of “Frost/Nixon” director Ron Howard — as a president from Texas, Esker Scott Anderson, aka Lyndon Baines Johnson. — Anthony Hopkins in “Nixon” (1995). Directed by Oliver Stone, “Nixon,” like “JFK,” is an overwrought, unfocused mess. Hopkins strives mightily to hold the film together, huffing and puffing and straining like the last man in a tug-of-war contest, but mostly all you remember is that he sweats more than even Nixon seemed to.

So strong has Nixon’s imprint on political movies been that many see Nixon in characters when he isn’t there. For years, it was believed that Cliff Robertson’s reptilian presidential candidate in Franklin Schaffner’s “The Best Man” (1964) was modeled on Nixon. Gore Vidal, author of the original stage play and the screenplay, has said he was not aiming for Nixon, but that doesn’t mean that Robertson didn’t play him that way. Anti-Nixon aficionados even claim to see a premonition of his Watergate unraveling in Humphrey Bogart’s “strawberries” speech in Edward Dmytryk’s “The Caine Mutiny” (1954).

In a sense, though, all actors, no matter how great, are at a disadvantage playing Nixon when compared to the man himself. What fictional Nixon could possibly contain the qualities of fake humility, forced pomposity and desperate longing for approval as Richard Nixon himself did? For purists, there can never be any real Nixon but the real Nixon. Richard Nixon was better in the role of Nixon than Laurence Oliver was as Hamlet, and he was never better than in underground filmmaker Emile de Antonio’s 1971 comedy, “Millhouse: A White Comedy.” You can see and hear most of Nixon’s biggest hits, including his breathtakingly self-pitying “you won’t have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore” speech (after losing the 1964 California gubernatorial race to Pat Brown).

A marvelous bookend to de Antonio’s pre-Watergate documentary is the three-volume set of the actual David Frost interviews with Nixon, just released on DVD. They stand, perhaps, as his final monument. Nixon is everything you want Nixon to be: reflective, sober, semi-contrite, and more full of fake sincerity than a TV evangelist begging forgiveness from his congregation. Here, at last, the little door opens in Nixon’s head and the phrase by which he best deserves to be remembered pops out at a startled Frost: “If the president does it, it’s not illegal.”

How much better America would be if every president were so candid.

Allen Barra writes about arts and sports for The Wall Street Journal, among other publications.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.