‘9500 Liberty’: Documenting the Immigration Debate

The new documentary “9500 Liberty” is about the struggle over a law requiring police to question anyone they have probable cause to believe is undocumented This premise may sound awfully familiar.

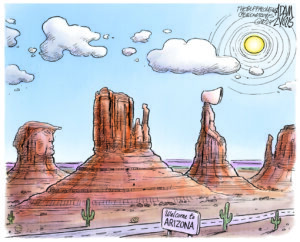

The new documentary “9500 Liberty” is about the struggle over a law requiring police to question anyone they have probable cause to believe is undocumented. This premise may sound awfully familiar, but the film isn’t about SB 1070, the controversial immigration law recently adopted in Arizona; rather, it’s about a 2007 resolution in Prince William County, Va.

Annabel Park and Eric Byler, the directors of the movie, posted footage of the debates over the resolution on YouTube, which drew tens of thousands of hits in just days. The two have a lot of experience with new media and civic engagement. They also created a website, Real Virginias for Webb, to support Jim Webb after his opponent, George Allen, used the term macaca when talking about an Indian, and they established the 121 Coalition to support passage of U.S. House Resolution 121, known as the “comfort women” resolution. Byler has made several feature films, including “Charlotte Sometimes,” and he and Park are co-founders of the Coffee Party USA, a political action group. Truthdig contributor Emily Wilson talked with them when they were in San Francisco for the opening of their film.

Emily Wilson: In the opening scene of the documentary you have a man yelling at a group of immigrants, telling them to learn English. Why did you choose to begin with that?

Annabel Park: We talked about that a lot. It kind of embodied so many components of the debate and the story, not only because it’s a very dramatic argument where the division is very clear, partly because there’s a fence. You have one person on one side of the fence and a group of people on the other side of the fence, and the group had this big sign. They were gathering in front of a sign that said “Stop your racism against Hispanics,” and it was a sign that a Mexican-American man had put up on one part of his wall. It was a house that had burned down, and he left this one wall and put up a sign to protest. We were there filming the immigrants when this man came over and started yelling at them saying, “Learn how to speak English,” “You don’t belong here,” that kind of thing. It caught us by surprise, and we ended up becoming involved in that discussion. I started talking to him, saying, “Why are you upset?” and trying to get him to understand what their situation is. And I put my hand out to shake his hand, and he grabbed my hand and started really talking to me. And this wasn’t in the film, but we had a long discussion of the Asians who came here before the Hispanics.

The idea for me was we have this fence, and the fence itself made the guy feel safe about actually screaming. I tried to imagine the whole scene without the fence there and he’s just approaching them. I don’t think he would have used that level of tone. I feel like in many ways the solution to what we have through this polarized situation is to get rid of the fence, literally and figuratively, so we see each other as equals and human beings. My hope is that with the film we can start to get rid of the fence and help people to engage with each other, understand one another, and I think we’ve had some success so far. We showed the film in Arizona, and I certainly felt that people were ready to have dialogue after watching the film.

EW: How did people respond to the film in Arizona? What was the reaction like?

AP: The response was overwhelmingly positive. We did a bunch of Q&As and we had a couple of people say “Well, illegal is illegal” — that type of rhetoric. But on the whole, people wanted to talk. And I think they were ready to go beyond “Illegal is illegal” and “You’re separating families,” to let’s look at the details of this thing. How is it really going to affect us? What does it really mean? That’s what we’re hoping to do nationally.

Eric Byler: There’s a direct parallel with what happened in Arizona because the law was written by the same anti-immigration law firm in D.C. So the people you meet in the middle of the film in that hearing are the ones who are behind SB 1070. It’s a kind of boilerplate of laws that are designed to divide the community, but it’s also a political strategy because it always happens right before an election. There’s really three pieces. First, an undocumented immigrant commits a crime that’s easy to exploit in the headlines.

AP: Or they think it was an undocumented immigrant.

EB: Oh yeah, in the case of the rancher, they don’t know who killed him, but they found footprints leading to the south, so they know for sure it was an undocumented immigrant because you can tell by their footprints. So they sensationalize the myth that undocumented immigrants are responsible for crime and then politicians who are in need of an issue and then comes the legislation. So what normally happens is the legislation is mostly just a political football, it’s for the election. It’s not really for the sake of policy.

EW: Why did you put what you were filming up on YouTube?

AP: I think after the first day of shooting I felt like we could easily do a feature film, but I think it wasn’t until we started realizing how misinformed people were about this issue that we felt the need to start sharing it because it would just be irresponsible not to. I mean if you have all this information and people are trying to make decisions on misinformation do you just do nothing? I’m hoping more filmmakers will do the same thing. They’re doing very timely documentaries, but it takes a year or more to actually share it with the world. EW: Why do you think you got so many hits with your YouTube videos?

AP: The video that went viral had the word racism in the title. I think people are triggered by the idea of race and racism. Everyone has an opinion about it, but it’s very hard to talk about it in any constructive way, so I think people are looking for ways to talk about it in any constructive way. I think any time you put something out there talking about race and racism, it tends to get noticed. It’s one of those issues we long to talk about but don’t know how.

EW: How did you make the decision to make a more conventional documentary?

AP: I think we were always hoping we had enough there to turn it into a feature film to tell a complete story. Because when you have three-minute videos, it’s really not a complete story. There are stories that you can get out there, but we wanted to give people a comprehensive understanding of what happened and our personal journey. I think that the power of filmmaking in general is to get to people’s imagination in a deeper place then just their political positions by introducing people to human beings, real characters and their stories. Then you relate to immigration in a different way. It’s not just about policy, it’s not just about politics, you’re talking about these children, you’re talking about these people, and you’re talking about your own future. It’s that kind of take-a-step-back, bird’s-eye view that I think people need in a very volatile conversation like about immigration.

EW: How did you get so much access to Greg Letiecq, the head of Help Save Manassas and the controversial blogger who pushed for the legislation?

AP: I think at the time he was really proud of what he was doing. I think he probably feels good about the film in a way because we do allow him to talk, and it helps him to get his message out.

EB: And he felt good about the videos. Initially I e-mailed him and I let him know about Real Virginias for Webb because it was very easy for him to look up my name and that would come up. Of course he thought of Jim Webb as a bad senator, so I said we may not agree about some things, but I pledge whatever format this movie is shared with the public to make it a true representation of who you are and what you’re doing. I think that he looked at us as an amplification of the magical rhetoric he had concocted that was already spinning a web that was enveloping the county. If he could reach even more people through YouTube that would only increase his power.

EW: Why do you think he was so effective and his blog so drove this debate?

AP: I think we have a kind of political discourse that uses words that trigger a strong emotional reaction. It’s been done this way for a long time and some people are really good at it. Greg happens to have a certain gift for that. To be able to frame things in a certain way that would get people to think, “Oh yeah, that’s the way to see it.” Even with these ideas like “Illegal is illegal,” someone came up with that. In terms of policymaking it’s completely empty. It doesn’t tell you how much money we should spend. It doesn’t tell you what the law should look like, but you think, “Oh, yeah, that’s my position ¬– illegal is illegal.”

It really speaks to the level of discourse we have, and I think Greg is someone who’s learned how to manipulate it. He’s learned how to get misinformation out there like the Zapatistas are invading the county. Another one was we’re spending $60 million on English as Second Language in the county. Well, if that’s true, anyone would freak out, but it’s just not true, but these things got disseminated so quickly, and that’s the part that really worries me. We saw an example in Prince William County where you have a government that is just so vulnerable to the extreme few people who are organizing, and it’s not a democratic process because the majority of the people didn’t get a chance to speak up. And by the time they had an opportunity, it was so ugly and divided, most people just opted out.

EW: Do you think the response in Arizona was similar to what you saw in Prince William County?

AP: I think in Prince William County people were caught off guard. Immigration really wasn’t on the radar for most people, whereas in Arizona it’s always been an issue, so there was that difference. But the similarity is that I think most people are just not speaking up, so this is an issue that is being left up to people who are the most passionate whatever position you’re in, so the majority of the people are just being silent and opting out. That’s what we need to change. In general as a country, I think that’s what we need to change. We have to get the majority of people in a dialogue about these issues so that we don’t become polarized. We can’t approach everything as if we’re divided, and it’s about who wins and loses. We just can’t. It’s not sustainable.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.