Big Banks Get Billions, Waters Gets Busted

Broadway and Central Avenue in the Watts area of South Los Angeles are lined with dozens of small, marginal businesses, but hardly any banks. In a capitalist economy, these are streets without capital, losers in the race to the top. Waters has spent years trying to help minority-owned banks. Her relationship with one of them, OneUnited, got her in trouble.

Broadway and Central Avenue in the Watts area of South Los Angeles are lined with dozens of small, marginal businesses, but hardly any banks. In a capitalist economy, these are streets without capital, losers in the race to the top. That helps explain—although perhaps not excuse—Rep. Maxine Waters’ current troubles in her relationship with minority-owned banks.

Waters has spent years trying to help such banks. Her relationship with one of them, OneUnited, got her in trouble. The board of the independent Office of Congressional Ethics said “there is substantial reason to believe” she advocated for a $51 million federal bailout for the bank while her husband, Sidney Williams, a former member of the OneUnited board of directors, had investments in it valued at between $500,000 and $1 million — assets Waters had reported in her official disclosure statement.

In 2008, she arranged a meeting between the bankers and Treasury Department officials. The bank eventually received $12 million in bailout funds. Waters said she had nothing to do with the bailout award, but the ethics investigators say she violated House rules. On Monday, the House ethics committee charged Waters with three counts of violating the letter and spirit of House rules.

It’s easy to see this as just another House member trying to use her office to enrich herself. But it can also be interpreted as something much different—an effort to help a bank bringing capital and jobs into a poor area underserved by the banking industry. OneUnited, which also operates in Florida and Massachusetts, has three branches in the South Los Angeles area.

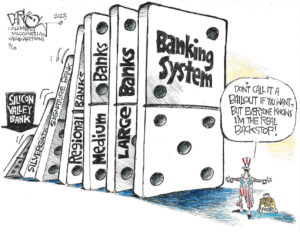

The case also raises the question of whether Waters and OneUnited are being treated differently than the giant Wall Street firms with Washington connections, firms that received billions in bailout money.

Maxine Waters, whom I have known for many years, grew up in a poor African-American home, one of 13 children raised by a single mother. She worked her way up from a garment factory floor to Congress and political dominance in South Los Angeles. She was an influential state legislator before her election to Congress.

Waters is difficult, sometimes almost impossible, to deal with. For example, a number of years ago she was supporting a young candidate running in South Los Angeles for an L.A. City Council seat. I was covering the race and had spent the afternoon with another candidate. By evening, it was raining hard and the rival of the Waters candidate offered me a ride to the next event, a community forum at a school. The man being supported by the House member saw me leave the car of his opponent. Early the next morning, Waters called me and commented on it. Very interesting, she said. It was raining, I explained, and I didn’t know how to find the school. She listened and said she was sure I would be fair in my coverage. There was just the hint of intimidation in her voice.

The Maxine Waters Employment Preparation Center is an example of what Waters has contributed to her district. Last week, a couple of days after the ethics report on the bank came out, I drove over to the center’s main campus, at 109th and Central avenues in a Watts neighborhood of old bungalows and housing projects, an area with problems including gangs, drugs, alcoholism, domestic violence, diabetes, AIDS and more. “Every negative a community has, this community has,” Dr. Janet K. Clark, the principal, told me.

But the hallways of her school were clean and bright, painted by the students in soft, relaxing colors designed to make the place a peaceful haven from the dangerous world outside. Clark saw a few students in the hall. “This isn’t a social hour,” she said, sending them back to class.

The center, with 3,000 students on the main campus, offers general education diploma courses for dropouts and classes in automotive repair, electrical work, construction, nursing and other skills.

Along the wall of the nursing classes were pictures of graduates smiling in their uniforms. Pete Cerda, the welding instructor, showed me a large room full of modern equipment and a scrapbook containing first paycheck stubs sent him by his former students. These paychecks, in a small way, are putting capital into the community, as are the licensed vocational nurse graduates from the school.

Clark pointed out equipment purchased with a $198,000 earmark arranged by Waters. The congresswoman’s aggressive style was evident last year when she tried to get a $1 million earmark for the school. Democratic Chairman David Obey of the House Appropriations Committee turned her down, saying he opposed giving money to any project named after a House member. Waters and Obey ended up in an angry exchange, an incident I am sure did not endear her to some Democratic leaders but one that is very much in the Waters manner.

Waters’ troubles began when the chief executive officer of OneUnited, Kevin Cohee, asked her to help his bank. She said she and Cohee were friends through her husband’s membership on the bank board. Cohee had held a fundraiser for her at his big beach-area home in Los Angeles.

OneUnited invested heavily in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac stock, and when the two companies collapsed and were taken over by the government, OneUnited faced insolvency. According to congressional investigators, Waters told Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts, who heads up the House Financial Services Committee, that OneUnited had a problem but she didn’t know what to do about it “because Sidney’s been on the board.” She said she knew she should say no to the bank, but it bothered her. Frank said it was clearly “a conflict-of-interest problem.” He advised her to “stay out of it.” He said he’d take care of it. OneUnited, which operated in Boston, was among the minority banks hurt by the recession that Frank was trying to help.

Nevertheless, Waters called then-Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson Jr. and set up a meeting, ostensibly to discuss the general problems of minority banks. A meeting was held, although neither Paulson nor Waters attended. Subsequently, OneUnited received federal bailout funds.

So did Goldman Sachs, whose connections to past and the current administration officials are deep and old, with top Goldman officials in revolving-door employment in the company and the government. Goldman received billions. In the current election cycle, it has given $505,025 in campaign contributions to Democrats and $446,750 to Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. What about Bank of America? Barbara Barrett of the McClatchy Newspapers reported that the bank, the recipient of $45 billion in federal bailout funds, spent more than $1.5 million lobbying on Capitol Hill as financial regulations were being discussed. The center says BofA has given $465,468 to Democrats and $662,185 to Republicans.

Waters is being punished for arranging a meeting, conduct considered acceptable when done on behalf of the well-connected Wall Street giants that met often and secretly with lawmakers and the Bush and Obama administrations during the bailout period. To me, this looks like a double standard.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.