America the Ingenious

Truthdig's Allen Barra speaks with Kevin Baker, author of "America the Ingenious: How a Nation of Dreamers, Immigrants, and Tinkerers Changed the World," which explores the incredible diversity of inventions and innovations that arose from our country.

Detail from the cover of “America the Ingenious.” (Artisan)

|

To see long excerpts from “America the Ingenious” at Google Books, click here. |

“America the Ingenious: How a Nation of Dreamers, Immigrants, and Tinkerers Changed the World,” by Kevin Baker, explores the kaleidoscope of paradigm-changing inventions that arose from our country. Truthdig’s Allen Barra speaks with Kevin Baker, a novelist, historian and journalist.Allen Barra

: Talk about inventing — I can’t think of another book like “America the Ingenious.” What was the genesis of your idea?

Kevin Baker: Thank you! Lia Ronnen, the publisher at Artisan, first approached me with the idea of a book about things Americans had invented.

Just what those things would be was left largely to me, though I discussed them thoroughly with Lia and Shoshana Gutmajer, who did a great job in editing it. We decided to make it 76 things for obvious reasons, but which ones?

I tried to avoid inventions that had been written about too much before, or that required too long a history. But above all, I wanted “America the Ingenious” to include the sorts of things that aren’t usually included in books like this. I wanted it to include, if possible, the full spectrum of American inventiveness, to show just how we did such things as inventing cities and entire musical genres like the blues and jazz.

AB: Canals, the space race, the Transcontinental Railroad, air conditioning, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Pennsylvania long rifle, the Southern California aqueduct, which made Los Angeles possible — surely this is the only book ever to include such diverse subjects. How did you come up with your list?

KB: These were all inventions that fascinated me over years of writing and reading about America. It was quite marvelous how one advance led to another, how the best inventions multiplied not only the wealth they provided but the social benefits to us all.

The Erie Canal not only reduced the amount of time it took to get goods and people from New York to the heart of the Midwest exponentially, it also produced an empire of productive cities and towns along the route, saved countless farmers and craftsmen from the bankruptcy they regularly faced because of the bad toll roads that had previously been their only way to market, and placed New York City in the cockpit of the Atlantic world at the height of the Industrial Revolution.

All that came from this one, crucial innovation! If that doesn’t make you excited about America, I don’t know what will. And there are dozens of examples.

AB: Time and again I was struck by things that were done 50, 100 or even 150 years ago that could be done today but just aren’t. For example, you have several chapters on trains. I think it’s worth repeating that the Transcontinental Railroad was not only built with aid from the government but during the Civil War. That cooperation between government and private industry just doesn’t exist today. Or am I seeing this wrong?

KB: I think you’re completely right. The men who built the Transcontinental Railroad were not going to lay a foot of track until they got guaranteed subsidies from the federal government. And the government, led by Abraham Lincoln, provided the funding. Lincoln never took his eye off the future even as he was fighting the most terrible war in our history.

The Transcontinental was everything [that] critics of government projects fear. There was massive corruption, there was theft, there was waste. But there was also genius, and courage, and innovation. And at the end of the day, all the corruption was a small pittance of what we had gained.

AB: I got a pang reading about the streamlined trains and America’s great train stations of yesteryear. Could we restore train travel on that level today?

KB: Loooove me some trains!

Certainly, there’s no reason why we can’t match or exceed our great national record of train travel. At one time, American passenger trains were beyond comparison with anything else in the world, and our freight trains are still the world’s best.

Could we do it again? No question. We’re never going to have a national trains system just like most of Europe does, with passenger trains connecting absolutely everything to the capital, or at least a couple of big hubs. America is just too large for that.

But we could certainly set up many terrific, regional passenger lines, and repair our increasingly shopworn freight system. Why not? After all, it was a pair of Americans, James Powell and Gordon Danby, who came up with the concept of magnetic levitation technology, which is now running the fastest trains in the world all over Europe and Asia.AB: Someone, I believe it was Henry Adams, said “Necessity may be the mother of invention, but accident is often the midwife.” Of all the inventions and innovations in your book, can you name something important that came about almost entirely by accident?

KB: Well, one terrific example is Willy Higinbotham, who invented one of the first ever video games, “Tennis for Two” — a predecessor to “Pong” — at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1958, just as a little amusement for visitors’ day. At the time, anything Higinbotham invented would have been the property of the U.S. government, so he might have wiped out the national debt, right then and there.

Another great example is Stephanie Louise Kwolek, who was looking to make a better tire, and came up with Kevlar, used in making bulletproof vests. It’s saved the lives of at least 3,000 police officers, and counting.

Then there were the devices whose inventors intended them for another purpose. Edison originally saw his phonograph as primarily something that would revolutionize business dictation.

AB: Would you call Edison the greatest inventive genius that we’ve ever produced?

KB: No one ever invented like Edison, who was a childhood hero of mine ever since my third-grade class went to visit his laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, an extraordinary place to visit and very well-preserved by the Parks Service.

The one person, or at least I would say the one American, who rivals him was Alexander Graham Bell, who many considered the greatest American inventor of all time, greater even than Edison.

I can’t say — except to point out that they worked in very different ways. Both were extraordinary men, and where their work overlapped, as with the telephone and the phonograph, they each ended up significantly improving the other’s original devices.

The breadth and depth of Bell’s intellect is astounding. I mean, this is a man who used to peruse the “Encyclopedia Britannica” as a little quiet bedtime reading, just to come up with new ideas. Besides his very significant work in phonographs and telephones, hydroplanes and airplanes, lifeboats and sailboats, airplanes, genetics and medical imaging, Bell also invented a “photophone” in 1880 that operated on a beam of light — something that he considered his greatest invention of all time.

Basically, this was fiber optics, over a hundred years ahead of anyone else! Bell also figured out that global warming was going to be a problem before the First World War. His genius was staggering.

Beyond what they invented, though, Edison and Bell each left such a wonderful legacy of invention. Bell with his Volta Labs helped inspire Bell Labs; Edison with his laboratories — though he did diminish his legacy somewhat with his constant lawsuits and attempts to gain full commercial credit for everything he had a hand in. But then, it was a cutthroat age.

AB: As a lover of aviation, I’ve always been interested in Donald Douglas, who gave us the DC-3. You quote a transportation historian who calls the plane “one of the most significant transport aircraft ever made.” I’m told there are still DC-3s flying in many parts of the world. What was it that made it such a great plane? Was it a triumph of ingenuity or simply efficiency and practicality?

KB: I would say, ingenuity, efficiency, practicality and sheer beauty.

Yes, the DC-3 was — and is — an extraordinary aircraft. There are thought to be over 400 of them still flying commercially today, which means in another 20 years or so they could become our first, 100-year-old airplanes.

The DC-3 was truly revolutionary in its day. Its stressed-skin, light aluminum covering and powerful, twin propellers made it possible to cut the time it took to cross the United States to just 15 hours in the 1930s, thereby enabling airlines to pull out the sleeper berths they’d had to have before, and make these planes all the lighter, and more maneuverable.

Most spectacular of all were the burnished silver squares of its skin, which made it a simply magnificent machine. AB: You revive the legends of some real characters in your book such as Walter Hunt, who was described as “a Yankee mechanical genius.” You don’t think of Hunt on the same level as other inventors and innovators, and yet the safety pin changed the lives of millions who were babies before disposable diapers were invented. He invented many amazing and simple devices — little luggage wheels for moving furniture called castor globes, repeating rifles, bottle stoppers, the modern fountain pen — yet he doesn’t seem to have profited much from his genius. Was he one of those who were just in it for the thrill of invention?

KB: Hunt, as you say, was a marvelous character, someone who kept getting to all these devices before anyone else and then all but giving them away.

He seems to have been marvelously naive. He had built a pretty fair sewing machine, for instance, but gave it up because one of his teenaged daughters convinced him it would put sewing women out of work — nothing could have been further from the truth.

At other times, he seemed to have his priorities all cockeyed. He gave away the patent for probably his greatest invention, the safety pin, for $400, in order to pay off a $15 debt.

Hunt just never seemed to have worried all that much about money, or at least getting the money he deserved for his inventions. He just liked working in his little shop, and speculating in Manhattan real estate, something he was spectacularly unequipped for.

AB: Some of your inventions don’t even have inventors — not in the usual sense. In your chapter on jazz, you ask who invented it, and answer, “Why, all of us to some degree.” Could you elaborate on that?

KB: As Geoff Ward has pointed out, jazz comes from cultures all over the world — from Africa, to Ireland, to South America, even from Arabia, originally. Rhythms from all these places can be found in it because, like the country that invented it, jazz takes in new ideas, new themes from everywhere.

Jazz is, undeniably, something that was invented primarily by people of color in this country (although some whites did try to deny that for a long time). But it went out into the world, and was added to, and enhanced, and is changing to this day. Much like America.

AB: If I could ask you to sum it all up in a couple of sentences, why did all of this happen here and in so short a time span?

KB: To answer in one word, I’d say, “Freedom.” But there are plenty of free [societies] who don’t invent anything like what America does.

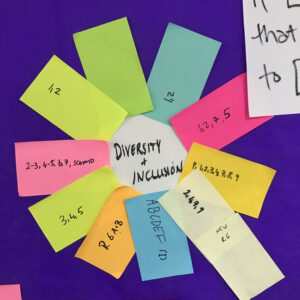

It’s a combination of things that guarantee and enhance that freedom: 1) our rights, as articulated in the Constitution. The opportunities that our economy and society encourage, which in turn attract immigrants, who are vital to so many of the inventions in this book. 2) The rule of law: a government that judiciously settles competing claims between inventors, thereby making success possible. 3) Government support: everything from the direct subsidies to the enforcement of the antitrust laws, have galvanized personal initiative. And finally, 4) propinquity: the many clusters of creativity and improvisation that have flourished in all sorts of forms throughout this country.

“America the Ingenious,” by Kevin Baker, is available from Artisan Books. Please support your independent bookstores.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.