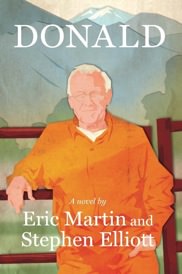

‘Donald’: A Black Site of Rumsfeld’s Own

On Feb. 8, the same day that Donald Rumsfeld's memoir "Known and Unknown" was released, McSweeney’s cheekily launched its own treatment of Rumsfeld's legacy in the form of "Donald," a satirical novel by Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott. Here's an excerpt from Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott's "Donald," a satirical novel that imagines the former defense secretary caught in a trap of his own making – and in an orange jumpsuit.

Editor’s note: On Feb. 8, the same day that Donald Rumsfeld’s memoir “Known and Unknown” was released, McSweeney’s cheekily launched its own treatment of Rumsfeld’s legacy in the form of “Donald,” a satirical novel by Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott.

As McSweeney’s put it on the book-centric section of its singular and highly addictive online smorgasbord, “ ‘Donald’ is a fictional exploration of this startling question: ‘What would happen if Donald Rumsfeld, former defense secretary and architect of the war on terror, was abducted at night from his Maryland home, held without charges in his own prison system, denied a trial, and kept in a place where no one could find him, beyond the reach of the law?’ ”

Truthdig is pleased to present this excerpt from the first chapter of “Donald,” in conjunction with McSweeney’s and co-author Elliott’s own excellent Web hub for literary enthusiasts, The Rumpus.

He is reading. The library is empty except for two limp scholars by the window. Look at their posture. How much butt would he have kicked here? The place is old, the oldest library in an old town. It’s too dark but the scholars don’t seem to mind. They’re twenty years younger than him, but he could outwrestle them. Them and every scholar in his weight class in every library in the world. His scholarly skills are not shabby, either. He reads like lightning. His hands are always moving, wringing ideas from the page. “Like a perv,” an assistant aide’s assistant once observed, and if by that she meant the body is the mind then fine, nice jab, he could give a rat’s how it looked. There’s a reason she was an assistant’s assistant. A reason generals and bureaucrats waited for a turn with him, turns that by well-publicized accounts were not all pleasant. But was he fair? He was so fair. He was so fair he screwed himself all the time.

He does not know the kid who sits down across from him, leaning two pointy elbows on the table. Six feet tall, soft 170, swallow’s nest of hair. The girl watches from three steps behind. He can’t tell if she’s ridiculously beautiful or if that’s just what girls always look like when they’re twenty-five. Good lord god almighty.

“Sir,” the kid says. “Good afternoon.”

Silence circles the drain. The kid’s got something. Head still. Hands away from his face. “Quick,” he tells them, finally, “I’m old, you know. Ha ha ha.” He smiles at the girl. Her short blond hair is blinding atop her cream-colored cashmere sweater. She smiles back. Her mouth looks very organized and fertile, and she looks like she knows her boy’s set to get reamed, and that’s fine with her.

“Not that old,” the kid says. “I’ve followed your career with interest.” Here comes the nervous hand now across lips and chin, unable to hold its position. No ring, no watch, thin fingers.

“Well hasn’t it been interesting.”

“Start to finish,” says the kid.

“Oh am I finished?” His best grin, tops and bottoms. He winks at the girl and she doesn’t look away. “Absolutely right,” he says. “I’ve sure been blessed in that department but it’s all over now, like the good song says.” From the shelves, thousands of books lean down on them, oozing leather, arcana, decay. “I won’t waste your time,” the kid says. His voice is nasal and he tries to go down low to hide it. Your voice is your voice, there’s nothing to be done. “The commission is going to request that you testify. We would like to flesh some things out prior, as your schedule permits.”

“What’s this we, white man?” He checks to see if she gets the reference, or anything for that matter. She’s grown stony. Her sweater is beginning to look scratchy.

“I’m ghosting the report,” the kid says. “There are omissions in your account. We’re looking to set baselines for productive dialogue.” The library is listening now. Wide knotty floorboards stand on tiptoe and gated presses lean around them. A shelver watches, gripping two black centuries in his hands. The scholar studying trench songs clicks his pencil. Time eases off like a dusk wind. He’s missed this.

He idly slides a book about Interwar naval innovation across the table. “I’m retired,” he says. The kid is trying to maintain eye contact like he learned it just last week. Get a name. Don’t look away until you’ve logged the color of their eyes. The girl’s are grey, the kid’s turd brown. He doesn’t care about their names. “How retired I am is reading books less pertinent than the crap you took this morning. Pardon my.”

The girl winces. She looks like she remembers that crap well. There’s something familiar about her. Who? Someone’s daughter. Her thin top lip is half-pointy, like his successor’s come to think of it, or maybe not, it could be nothing, except it can’t be nothing the way scorpions are scrabbling through his throat. This library is supposed to be members only, military and safe. Who let them in here?

“There are things in this report,” the kid says, “things that are going to break hell loose, and I do want—the commission, we—to give you due chance for answers and the record.”

His successor’s daughter watches to see how the old man takes it. His thinning hair is parted. His undershirt is dry. He glances at her and she smiles again—nope, the mouth is different, too big and garish, too unseri¬ous—and he smiles back. A glut of smiles as if they’re sipping cocktails instead of starting the gorilla dance. Perhaps she’s never attended a ream¬ing. There are two real kinds of people in this world. Deep down, she must know that her boy is neither of them.

“The record.” He pushes on his rimless glasses, tilts his head, and gives the kid his strangler look. “Aren’t these books the record, all around us?” The kid was not brought up to see books as wholes, only collections of data that could be boiled down, context stripped out. He could know the kid’s age, the kid’s cholesterol, the kid’s genome and test scores, the diameter of the kid’s unit, and yet would he know the kid? “You want to add to the record? What’s the question? Ask me. Now.” He uncurls a pinky and wiggles it. The girl looks like his own wife.

“Okay,” answers the boy, and he knows he’s made a big mistake.

The girl doesn’t look like his wife. The girl is slender and blue-eyed but she doesn’t look fun. It’s the face shape that’s the same. A circle composed of perfect little squares, round and rectangular at once. He’s met movie stars possessed of such-shaped faces. He has met dictators’ wives. But not many. His wife has aged comprehensively but he still sees that shape, even when he’s far away, even with his arms, legs, and eyes closed tight around her, even if conditions on the ground have changed.

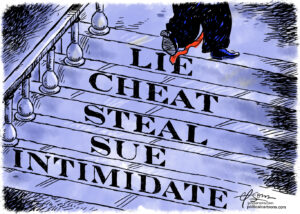

“The practices you authorized,” the kid begins, “have always been the exception to the rule, the ugly facet of what nations do to survive and thrive.” The kid is angry, and his anger has smoothed his jitters away. Even his nasal voice sounds cleared up by adrenaline. “But you made it the rule. You called it legitimate. You sat next to the throne and offered pre-forgive¬ness for grave sin. And the world will never forgive us that.”

The kid’s blood is about to slough the skin off. If he wasn’t such a kid this is when he’d call security, but this kid? This? These are his enemies now? This guy instead of the suicidal hostile or the one-legged mountain¬man on horseback cum machine gun? The hubris. And yet he had done it, too. Sitting in a library writing treatises on factory seizures and executive power. He leans back twisty in his chair, belly out, shoulders wide, chin up, offering his nape. “You two married?” Triangles of light and shadow are moving across the broad oak table, poking their long fingers into the old biographies. It’s going on four. He’s got a drive ahead of him, dinner plans, a wife and guests. The kid and girl are wilting. “Married. Two. You.” The kid doesn’t move and the girl rolls in her bottom lip. “Not my business. Absolutely right.” The kid is someone’s son but who isn’t? “My life, on the other hand, has been a public life and so my life is now your business. Your report. The book you’re no doubt writing, as I am. Your history in progress.” He breathes in deeply through his nose, takes in the musk of old books and fear. “Characterized by excellent verbs and a personal touch. A wealth of secondary sources from the public domain. Your perspective as I guess a citizen. As I guess a man.” The kid is someone’s grandson and every boy is someone’s grandson. “Who has faced the threats and opportunities of this age and other larger stuff, with resolve and a profound sense of those who came before.” The girl is smiling. Her mouth is doing something at least, jagging at the sides.

“You are going to have to answer,” says the kid. His young throat beats like a jogging heart. “Things have changed.”

“They always do,” he tells the kid, “but never as much or fast as people think.” He leans forward across the table and spreads his arms in front of him, hands joined in a power triangle. “Tell me who you are.”

“I’ve written—”

“No. Something real. A decision you made.” He glances at the girl. “A real one.”

The kid brushes his hair out of his eyes and looks, for that time it takes a person to push hair from the middle of the forehead towards the left ear, about twelve years old. Late afternoons perched on a thick branch over the garage. Kick the can with his sister in the neighborhood. Smear the queer. Stealing gum. Lighting weeds with matches. Five. Nine. Twelve. A hand¬stand on the gunnels of a canoe, diving off the no diving sign. Days of the body. “What are you talking about?” the kid says.

“That’s what I thought.” Down there in the kid’s eyes, Donald sees broad leaves of intelligence but rooted in such soft soil that it might as well be sand. A zen garden. With a few green wisps that will blow flat at the first breath of wind. The world they live in is a blustery place. This is the son of a father who never went to war. There’s a little war in the girl, maybe from her father, or maybe because every beautiful girl has glimpsed the natural state of man, at least the part that would rape her if it could. “Tell me,” he says to the girl, “he had to choose between his sick mother and his career. Or he won’t marry you but made you give up a. He put a dog down. He sent a buddy off to jail. You betrayed him, he forgave you. Tell me there’s something that’s happened in his life but do not ask me what I mean by what’s real. Because if you don’t know that, you really don’t know anything. Success is the exception. Failure is the rule. The record,” he tells the kid, pounding the table in front of him, a seismic event that ripples through the hall, rattling the books and cages and centuries, “the record is unlikely to be kept by the likes of you.”

The kid’s mouth pops open like a bottom-feeding fish. His plan has not survived contact with the enemy. The enemy is never who you think it is, and you are seldom who you think you are. That’s what the girl is ruminating as the light now stabs her cheek, a late low PM icicle of sun that points out inex¬pert flakes of makeup. What a waste. “Get married,” he says. “Get married, have a family, children, hit the beach, let them run naked. Write poetry about sex and rock n’ roll. Paint, play tennis, find some land. What are you waiting for? What are you doing here? The world’s not getting any nicer, is it?”

“You should have been a source of restraint,” the kid says, his voice dipped and thick now. “And you were not a source of restraint. You should have been. You used to be. I want to know why.” “We are not what’s wrong with the world,” he assures the kid. But the kid has surprised him. You used to be? Like he’s a cop gone bad betraying his partner in some hackneyed flick? There’s a reason the kid got in here. Find out. “People are seeing things they’ve never seen before. So let those of us who can deal with it deal with it. The rest of you should find some happiness where you can.”

The kid snorts. His nose sounds clogged again. It’s crooked, but not like he broke it. Crooked like a sick tree. “I’m not here to—”

“My daughter,” he cuts the kid off, “told me once that it takes everyone to make a happy day. Nine years old.” She’s middle-aged now, gracious, grown and long, a happy housewife who could have done anything. Her choices weren’t good but she made those choices work, except the marriage, of course, but he could have told her that. Did tell her. She could have had anyone. She was like her mother. Guys stuck to her like glue. There was something childish and poetic about her. Sweet, popular, laid-back, cool, courteous, gracious, accepting, pretty, skinny. Her weaknesses a glut of trust and dearth of judgment. Right ladder, wrong wall. She’d run away to the sunny west to study history but came back home—the only one who had—and now look at her! A mother to her children and to other children, on the board of countless schools and education projects, a philanthropist, a caretaker, although was she ever as wise as she was as a child? “This wise little girl lived a pretty comfortable life, you know, and she still knew how difficult it is, the perfect storm of happiness. And the thing is, I would say that I’m an optimist but I’ve always thought the other way of putting it was that it only takes one jerk to crud things up for everyone, and that means you have to avoid or isolate or neutralize that bastard best you can. If he’s ready to strap a bomb to his chest and kill innocents? Women, children, civilians. Poison them, infect them, crumble your cities, make you die and suffer any way he can with whatsoever he can get his hands on? When you’re nine, you’re looking at the world as a circle of playmates for happy days ahead, but none of us are nine here. You go out into the world?” The clock above her head is screaming at him. “Happiness can happen, but there’s always—always—some vicious animal out there waiting. And after him, there’s another.” He hasn’t felt like this in a while, filling a room, leaving just the tiny last nooks for them, the slits and grottos. “There’s another and another, and people like you need people like me to take care of them for you and shoulder the cost, because you? You people?” He reaches across the table so quickly that the kid can’t even flinch. He holds the kid’s hand, palms the long thin fingers, and presses them gently flat. Then he shakes his head on its slowest setting, softly, side to side.

His left knee pops as he stands but he makes sure it doesn’t register across his igneous face. The spell holds. He can still get out of here before he turns into an old fart again. “I hope,” he tells the girl, “you two get out there and prove me wrong.” She is beautiful after all, not like his wife, but in her own way, and he’s glad she was standing there to help him be his better self. But it’s undeniable: the kid is on the wrong side; the girl’s got the wrong boy; and he, unless some extraordinary piece of luck strikes, is going to be late for dinner.

Copyright © 2011 by Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott from “Donald.” Reprinted by permission of McSweeney’s.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.