The Revolutionary Refused the Torch

"Master of the Mountain" by Henry Wiencek reveals that Thomas Jefferson's slavery practices evolved not in moral terms but in commercial ones.

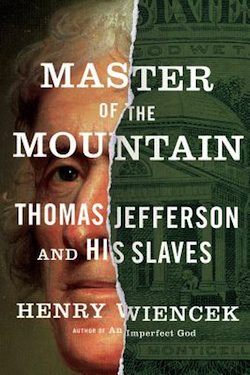

“Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves” A book by Henry Wiencek

“On the first day of April in 1819,” Henry Wiencek writes, “a group of seventeen slaves left a plantation in the mountains south of Charlottesville … bound for a distant destination.” Leading their way was a 32-year-old white man named Edward Coles, “a wealthy, politically prominent Virginian” who no longer could resist the call of conscience and was taking his slaves to freedom in Illinois, where he gave each head of family 160 acres of land and where he himself was to settle. One of his family’s friends was Thomas Jefferson, the former president and author of the Declaration of Independence, whom Coles had attempted to persuade to join this undertaking. He “did not ask Jefferson to free his (own) slaves immediately, but to formulate a general emancipation plan for Virginia and lay it before the public, backed by his immense prestige.” Coles approached Jefferson with deference, Wiencek writes:

“Referring to Jefferson as one of ‘the revered fathers of all our political and social ‘blessings’ and extolling the ‘valor, wisdom and virtue (that) have done so much in ameliorating the condition of mankind,” Coles then sharpened his pen and thrust it straight at the Founder: ‘it is a duty, as I conceive, that devolves particularly on you, to put into complete practice those hallowed principles contained in that renowned Declaration, of which you were the renowned author, and on which we founded our right to resist oppression and establish our freedom and independence.”

The Sage of Monticello — the man who had electrified the world with the bold assertion that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal” — was having none of that. As a young man Jefferson had called slavery “this execrable commerce,” a “cruel war against human nature itself,” but now, as a prosperous farmer and businessman, he retreated into equivocation (emancipation must be “gradual”) and insult: “Brought from their infancy without necessity for thought or forecast, (black people) are by their habits rendered as incapable as children of taking care of themselves, and are extinguished promptly wherever industry is necessary for raising young. In the mean time they are pests in society by their idleness, and the depredations to which this leads them.” That was that: “The revolutionary refused to take up the torch, and Coles turned his thoughts to Illinois.”

This exchange between the idealistic and determined Coles and the cynical, self-interested Jefferson is at the very heart of Wiencek’s brilliant examination of the dark side of the man who gave the world the most ringing declarations about human liberty, yet in his own life repeatedly violated the principles they expressed. This was rumored during Jefferson’s lifetime, as gossip about his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings circulated widely, and in recent years DNA testing has proved that her children were fathered by a member of the Jefferson family — virtually all the circumstantial evidence points to Thomas himself — but the emphasis has focused narrowly on the Jefferson-Hemings menage rather than on Jefferson as slaveowner. Now the record has been corrected, to devastating effect.

Wiencek has entered this territory before, first in “The Hairstons: An American Family in Black and White” (1999), then in “An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America” (2003), both of them important books about the tangled history of race in America. Nothing could be much more tangled than the personal history of Thomas Jefferson, who beyond dispute was brilliant, eloquent, passionate about the new nation he played so central a role in founding, yet who over the course of his long life “owned more than 600 slaves” and on the whole treated them not much better than did any other Virginian plutocrat to whom they were not human beings but capital, pure and simple. “I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm,” Jefferson told his son-in-law. “What she produces is an addition to the capital.” Wiencek writes:

Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves

By Henry Wiencek

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 352 pages

“Few biographical tasks are more frustrating than trying to assemble a montage of quotations from Jefferson’s written work that make sense of his stance on slavery. Among the completely contradictory points he advances about slaves and slavery we have: the institution was evil; blacks had natural rights, and slavery abrogated those rights; emancipation was desirable; emancipation was imminent; emancipation was impossible until a way could be found to exile the freed slaves; emancipation was impossible because slaves were incompetent; emancipation was just over the horizon but could not take place until the minds of white people were ‘ripened’ for it.”

As Wiencek says, “Laid end to end, his utterances present a rolling paradox of contradictions that inspire his detractors to call him a hypocrite, his defenders to call him compartmentalized, and baffled onlookers to call him ‘human.’ ” In truth he was all that and more, because his views and practices on slavery evolved not in moral terms but in commercial ones. As his plans for Monticello ballooned into a splendid monument to himself, he became a businessman whose “elaborate program … would make an excellent case study in business schools today.” Jefferson “the philosopher has been endlessly parsed, but Jefferson the on-the-ground manager is most revealing, carrying us closer to the truth of slavery than anything he wrote.” Wiencek adds:

“Again and again the sale, the hiring, or the mortgaging of black souls rescued the Jeffersons from a bad harvest, bought time from the debt collectors, and kept the family afloat while a new and grander version of Monticello took shape. … The slaves formed Jefferson’s bulwark against catastrophe. … In 1792 he calculated that the births of slave children produced capital at the rate of 4 percent per year: ‘I allow nothing for losses by death, but, on the contrary, shall presently take credit four percent, per annum, for their increase over and above keeping up their own numbers.’ In the 1780s and 1790s the astounding total of 143 children were born into Jefferson’s possession.” That chilling phrase, “I allow nothing for losses by death,” perfectly expresses Jefferson’s view of the human chattel in his possession. To be sure there were exceptions. Betty Hemings had been the mistress of the father of Jefferson’s wife. The children she bore by him and their children were bound to the Jeffersons by kinship. They remained slaves, but comparatively privileged ones who “lived and worked on the summit and in the house itself.” They “occupied a hazy no-man’s-land that (Jefferson’s) grandson, Jeff Randolph, struggled to describe: ‘Having the double aspect of persons and property the feelings for the person was always impairing its value as property.’ ” Indeed.

Leaving aside the unresolved (and probably unresolvable) question of whether Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings’s children, “The status of the Hemingses obviously raises doubts about Jefferson’s oft-stated opposition to the mixing of the races. If miscegenation disgusted him, why did he staff his household with his mixed-race relatives? Surrounding himself with these enslaved relatives — well dressed, well fed, highly trained — Jefferson created a buffer between himself and the harsher reality of Monticello’s slavery farther down the mountain.” That it was harsh is beyond question. Jefferson’s many apologists have long contended that he was a kind master, but “the Monticello machine operated on carefully calculated violence.” Jefferson fastidiously kept his own hands clean, but he said that some people “require a vigour of discipline to make them do reasonable work,” and he hired overseers, “hardhanded men who got things done and had no misgivings,” to carry out that discipline. In the 1950s the editor of a published edition of Jefferson’s “Farm Book” suppressed evidence that some children on the place, “the small ones,” were being whipped to keep them at their tasks, an “omission (that) was important in shaping the scholarly consensus that Jefferson managed his plantations with a lenient hand.”

Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves

By Henry Wiencek

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 352 pages

Jefferson whined constantly about “the kind of labor we have” on his holdings, but “we simply cannot believe Jefferson’s complaints about his slaves, which fit into his pattern of shifting blame to others for his own mistakes.” Among the most important of these were the debts he constantly ran up in order to satisfy his extravagant tastes: for fine French wine, a grand carriage with strutting horses, and of course Monticello itself, a hole down which an endless supply of money, much of it borrowed, was poured. “The consensus must be turned around,” Wiencek writes: “with Jefferson miring himself in debt, his slaves kept him afloat.”

No doubt the argument will be made that everyone did it, that it is “presentism” — judging yesterday by the standards of today — to single out Jefferson’s treatment of his slaves. That is not the case. Everyone wasn’t doing it. There were voices for emancipation in Virginia, and there were people who freed their slaves: “The long list of people who begged Jefferson to do something about slavery includes resounding names — Lafayette, Kosciuszko, Thomas Paine — along with the less-known Edward Coles, William Short, and the Colored Battalion of New Orleans. They all came to Jefferson speaking the Revolution’s language of universal human rights, believing that the ideals of the Revolution actually meant something.” Jefferson, who wrote much of that language, wasn’t listening.

Jonathan Yardley is the book critic at The Washington Post. He can be reached at [email protected].

©2012, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.