Yearning for Home: Undocumented Immigrants Challenge the Border

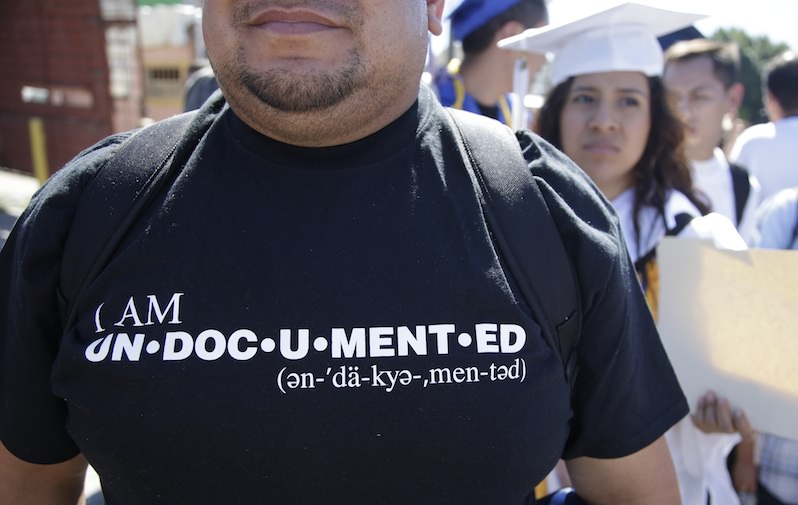

When I asked Edgar Torres how he felt about the fact that he would soon be spending the night at a detention center he said, "I honestly don't mind, I borderline don't care. All I want is to simply be able to go back home." A member of the group Border Dreamers and other supporters of an open border policy march toward the United States border, where some plan to ask for asylum, in Tijuana, Mexico, on Monday. (AP/Lenny Ignelzi)

A member of the group Border Dreamers and other supporters of an open border policy march toward the United States border, where some plan to ask for asylum, in Tijuana, Mexico, on Monday. (AP/Lenny Ignelzi)

When I asked Edgar Torres how he felt about the fact that he would soon be spending the night at a detention center he said, “I honestly don’t mind, I borderline don’t care. All I want is to simply be able to go back home.”

Torres was in Mexico near the U.S. border with San Diego, and two hours away from presenting himself to border officials when I spoke to him Monday. He was accompanied by more than 30 other undocumented immigrants who, like him, consider the U.S. their home and want to be let back in. Most had been deported for things like minor traffic infractions and some had voluntarily left due to financial difficulties and other pressures. Torres returned to Mexico in 2010 after 13 years of living in the United States. He was 7 or 8 years old when his parents brought him to the U.S.

With no viable option to emigrate legally back to their homes, Torres and his fellow immigrants decided to show up at the border and turn themselves in to the authorities. They risked not only being thrown into a detention center indefinitely like thousands of other undocumented immigrants, but also being deported back to Mexico right away if they were permitted to re-enter the U.S.

Their actions are the third chapter of a deliberate and coordinated effort by the National Immigrant Youth Alliance to force the U.S. government to face the human cost of our broken immigration system. In August NIYA launched its #BringThemHome campaign with nine young undocumented immigrants turning themselves in at the border. When that action resulted in all nine being allowed to submit asylum requests while remaining in the country, NIYA arranged for 30 more people to try the same tactic in October (about which I wrote here). At least 17 of them were approved to submit asylum requests, while seven were denied.

For those who were denied, the pain of family separation is ongoing and real. Rocio Hernández Pérez, 23, was the first in that group to be deported to Mexico for reasons that are still unknown. Hernández Pérez had lived in the U.S. since she was only 4 years old. Activists are campaigning for her to be allowed back in to the country based on fears of being killed by drug cartels. Her parents publicly posted a video of their heartfelt plea to be reunited with their daughter.

Immigrants like Hernández Pérez and Torres are often derided as lawbreakers by anti-immigrant activists. But they consider the U.S. their home and are usually not accepted in their countries of origin. Torres told me, “When people tell me we should go back home, what they don’t know is that we are considered the ‘Benedict Arnolds’ of that country. We put the U.S. first, before our own countries.”

Benedict Arnold was a U.S. general who defected to the British side during the Revolutionary War. In Torres’ case, it is perhaps a literal comparison; he told me that while living in the U.S., he strongly considered joining the U.S. Air Force or Navy.

The past four years that Torres has spent in Mexico have been difficult particularly because English is his first language. “There’s simply no fitting in,” he said. “I don’t even speak Spanish well. The jobs I had to get had to be in English. The entrance exam at the university was pretty hard because it was in Spanish. I passed the math with flying colors but every other thing I had a difficult time with simply because it was in Spanish.” Before he left the U.S., Torres had been studying robotics engineering, specializing in robotic prosthetic limbs.

After this latest border action, the fate of Torres and his fellow immigrants remains unknown. Family members are not informed of the plight of their loved ones at the border. Mohammad Abdollahi, an organizer with NIYA, told me, “This is very much a reality for us. When you’re pulled over [as an immigrant in the U.S.] and taken into detention, the immigration system is nothing like the criminal justice system in the sense that people are not given a phone call or allowed to call out. We haven’t heard anything from them.” As far as NIYA knows, the immigrants are either being processed or taken to a detention center.

Border officials have caught on to what NIYA is doing. Before this third campaign that Torres was a part of, immigration agents approached NIYA ahead of time to request a meeting. They wanted to know how many people to expect at the border, particularly if there were unaccompanied children or families with children, so they could be better prepared to handle the processing. Abdollahi told me the meeting was affable if awkward, with officials telling him, “We have children too, and we’ll treat them like our children.” But Abdollahi retorted, “I don’t know any parent who would put their child in a glass cell for 24 hours or pat down an 8-year-old and check his shoelaces.” Detention centers that house undocumented immigrants are privately run with little oversight. They are notorious for harsh treatment. Hundreds of immigrants have just launched a hunger strike at a facility in Tacoma, Wash., operated by government contractor GEO Group. The immigrants are protesting deportations as well as conditions inside the detention center. They are demanding better food, an increase in the $1-a-day wages for work, better treatment by prison guards and access to medical care. There are reports that the hunger strikers could be force-fed if they do not end their protest soon.

Detaining immigrants is big business, and companies like GEO Group have spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying Congress on immigration policies. Currently, activists are pressuring the Obama administration to end the so-called bed mandate requiring 34,000 beds be available each day to house immigrants in detention at a cost of $2 billion per year to taxpayers.

But the costs to immigrants and their families are incalculable. An analysis in Al-Jazeera America found a generation of young immigrants “scarred by parental loss.” Hundreds of thousands of children have lost parents to deportation and thousands are in foster care. The report cites psychological impacts such as “generalized anxiety, recurrent nightmares, depression, panic attacks and flashbacks.”

Abdollahi told me that families awaiting their loved ones on the U.S. side of the border were relatively calm. “A lot of them have walked through the desert before for weeks to make it to the country, only to be deported. So they realize the risks. Unfortunately that trauma is something that has become very normalized,” he said.

The fact that immigrants are detained, demeaned and deported has become a “normal” thing in the U.S. Close to 2 million immigrants have been deported under Barack Obama — more than under any president in U.S. history. But now groups like NIYA and the hunger strikers in Washington are demanding a different way. With immigration reform indefinitely postponed at the congressional level, there is little left for activists and immigrants to lose. Actions like the one in Los Angeles in December — during which undocumented activists blocked a detention center for transporting deportees — are becoming more commonplace.

Even municipalities are defying federal immigration policy: The Los Angeles City Council approved a resolution in December calling on Obama to halt deportations by expanding his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program to all noncriminal immigrants in the country. Several other cities are considering similar resolutions. And even Obama, in his latest budget proposal, offered to reduce the bed mandate from 34,000 to about 30,500.

But for people like Edgar Torres, policy changes are not coming soon enough. He has not seen his two younger sisters in four years and told me his mother had been up crying, awaiting his return to Texas where they live. All he wants, he says, is just “to go back to the country I believe to be my home. It doesn’t matter at what cost to me. As long as I can be with family, friends and be able to finish my degree.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.