Ethiopian Researcher Alleges Facebook Is Responsible for His Father’s Death

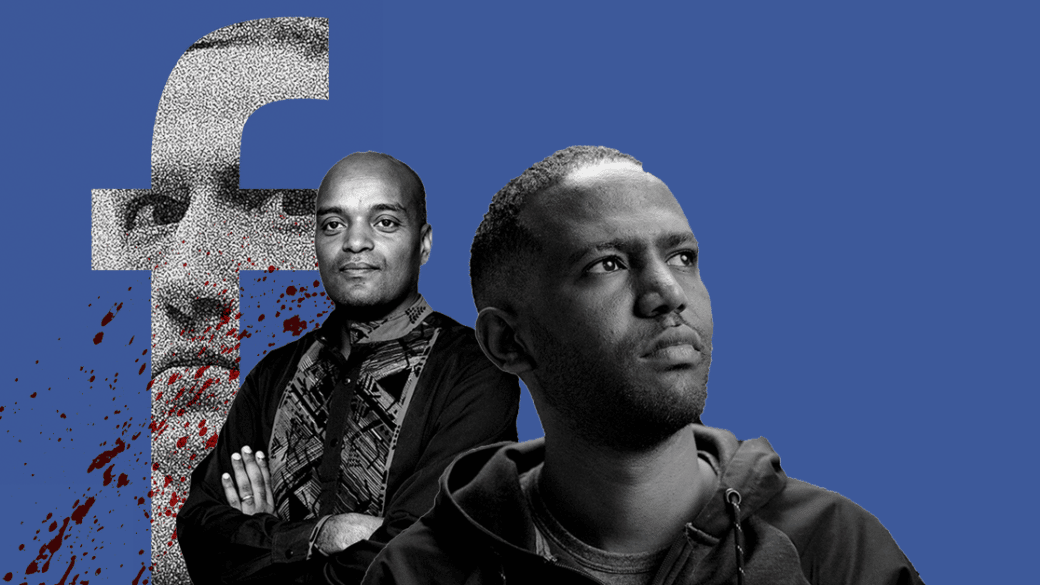

A new lawsuit claims the tech giant has failed to moderate harmful content that incites violence in Africa. Abrham Meareg / Foxglove

Abrham Meareg / Foxglove

This article was originally published on opendemocracy.net

A man who is suing Facebook’s parent company, Meta, has told openDemocracy he believes his father would still be alive if the social media giant better monitored content.

In a lawsuit brought in the Kenyan high court on 14 December, Meta has been accused of failing to remove posts inciting racial hate and violence in Africa, particularly in Tigray, a region in northern Ethiopia that has seen armed conflict for the past two years.

The case was filed by Ethiopian researchers Abrham Meareg and Fisseha Tekle, along with Kenyan rights group Katiba Institute, who allege that Facebook’s actions have led to “the loss of lives, displacement of families, vilification of individuals and destruction of communities in Kenya and across Africa”.

Speaking to openDemocracy, Meareg said he also holds “Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg directly responsible” for the death of his father, Meareg Amare.

Amare, a lecturer at Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, was killed in November 2021 by assailants who attacked him outside his family home. The new lawsuit says that a month before his death, a Facebook post called on people to attack Amare, and published his home address and place of work. The post garnered over 35,000 likes.

Meareg added: “Nothing will bring my father back, but I am fighting this case so no one needs to suffer as my family has ever again.”

Tekle told openDemocracy that Facebook also failed to regulate hateful posts that incited violent attacks against him in 2020, when he was working as a researcher for Amnesty International (AI).

Today, Tekle is a legal adviser at AI living in self-exile in Kenya with his immediate family. He says he has been unable to return to Ethiopia since 2020 due to escalating violence that has endangered his life.

Tekle said: “I’m now unable to go back home to Ethiopia because it’s not safe and this has affected my family and I. People have been told that I’m Tigrayan and related to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front leaders(TPLF) [a guerrilla group that ruled Ethiopia from 1991 to 2018]. This is false, but people believe what is posted on Facebook.”

He continued: “This case is not only about me but so many others such as Professor Meareg Amare, Abrham’s father, who was killed due to Meta’s blatant disregard of our safety. It is clear that Meta does not prioritise our lives and their business model is based on promoting viral content even in situations where there’s conflict and the content is inciteful.”

Meta could afford to prevent the dissemination of harmful content but actively discriminates in how it treats concerns from Africa compared to the rest of the globe

The men, who are seeking $1.6bn for victims of hate and violence incited on Facebook, want the California-based technology conglomerate to be held liable.

They also want Meta to enhance its content moderation in Africa to prevent future violence, through measures similar to those used in the US within hours of protesters storming the Capitol building on 6 January 2021.

“I demand that Facebook invests in safety and stops these tragedies. I hope the court will order the platform to fix its safety systems and hire more moderators so that violence and hate don’t keep spreading,” said Meagre.

Katiba Institute, a non-profit constitutional research and litigation institute, argues that Meta could afford to prevent the dissemination of harmful content but actively discriminates in how it treats concerns from Africa compared to the rest of the globe.

Speaking to openDemocracy, a public interest lawyer at the institute, Dudley Ochiel, said: “Katiba got involved in the case because it concerns the unchecked use of Meta platforms to spread hate speech and disinformation.

“With the large number of users from the region, and the potential for ethnic and other conflicts in Kenya and Ethiopia, Meta should do more. Kenya has about 70 ethnic languages used on Meta platforms, but Meta does not moderate in those languages.”

The effects of Facebook’s unregulated content have not only been felt in Ethiopia, the petitioners’ lawyer alleged in the statement on Wednesday, but have crossed into Marsabit County in neighbouring Kenya, where there has been an increased spate of violent attacks among local clans.

The case was filed in Kenya, where Meta’s sub-Saharan operations are based. Ochiel told openDemocracy this is where content moderation decisions “that affect the larger part of Africa are made”.

In a statement sent to openDemocracy, Victoria Miguda, Meta’s corporate communications manager in East Africa, said the company has strict rules against hate speech and incitement to violence, adding that Meta has invested “heavily in teams and technology to help us find and remove this content”.

Miguda continued: “Our safety and integrity work in Ethiopia is guided by feedback from local civil society organisations and international institutions.

“We employ staff with local knowledge and expertise, and continue to develop our capabilities to catch violating content in the most widely spoken languages in the country, including Amharic, Oromo, Somali and Tigrinya.”

Miguda added that Facebook is doing more to counter harmful content in Ethiopia, as outlined in Meta’s blog titled, ‘An Update on Our Longstanding Work to Protect People in Ethiopia’. The case has received support from several human rights organizations such as Global Witness, Amnesty International, Article 19, Kenyan Human Rights Commission, Kenya’s National Integration and Cohesion Commission.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.