Two Felons Could Force the Supreme Court to Protect Privacy in the Digital Age

The last thing we would expect from the Roberts court is a robust defense of civil liberties, but judging from the tenor of Tuesday’s oral argument, we could be in for some surprises. AP/Ahn Young-joon

AP/Ahn Young-joon

AP/Ahn Young-joon

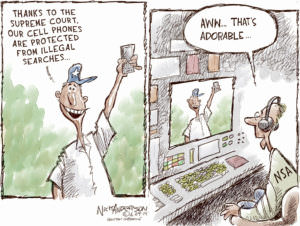

The renowned whistle-blower Edward Snowden and journalists Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald and Barton Gellman called the world’s attention to telephone data searches and violations of informational privacy at the hands of today’s surveillance state, and now David Leon Riley and Brima Wurie may have the best chance to persuade the Supreme Court to articulate new privacy standards for the 21st century.

No, Riley and Wurie aren’t fearless public-interest lawyers looking to dismantle the National Security Agency. Nor are they people of great conscience like Snowden, or intrepid investigative reporters like Greenwald and company. They’re convicted criminals serving hard time in California and federal custody, respectively, who just happened to have their cellphones on hand when they were arrested, and their phone data examined afterward without warrants or probable cause.

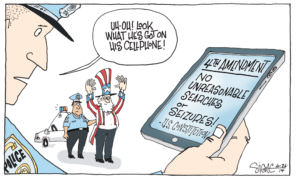

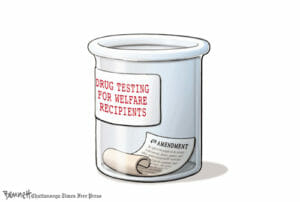

Riley’s and Wurie’s cases were argued before Chief Justice John Roberts and his colleagues Tuesday in a pair of consolidated appeals that raise constitutional issues about the right to informational privacy under the Fourth Amendment similar to those implicated in the controversy surrounding the NSA’s warrantless collection of telephone metadata. And although the cases aren’t likely to force the very conservative Roberts court to overrule the pivotal 1979 decision — Smith v. Maryland — that has been cited repeatedly by the Obama administration as authority for the metadata program, they could compel the tribunal to question some of Smith’s underlying assumptions.

In the Smith case, the court considered the constitutionality of the government’s installation at a telecom switching station of a “pen register” — a mechanical device that reads the electrical impulses generated by dialing a phone to identify the numbers called by a robbery suspect. By a margin of 5-3, with the great progressive Justices Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan dissenting and Justice Lewis Powell not taking part, the court held that capturing the phone numbers — but not the content — of calls made by a criminal suspect was not a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment, much less a Fourth Amendment violation. Because telephone users voluntarily surrender such information whenever they place a call, the court explained, they have no reasonable expectation of privacy in their call logs.

Echoing Smith’s rationale, an opinion written in August by Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Judge Claire V. Eagan held that the difference in scale between the NSA’s bulk collection of telecom metadata and the numbers dialed from a single phone in Smith was constitutionally irrelevant. The metadata program was legal, and the fact that Smith stemmed from a pre-digital age left Eagan entirely untroubled.

Equally unfazed, the Supreme Court rejected a petition challenging the metadata program and the continued validity of Smith brought last term by the Washington, D.C.-based Electronic Privacy Information Center. Subsequent conflicting district court opinions — one by a federal judge in the District of Columbia holding that the program likely violates the Fourth Amendment and the other by a judge in New York concluding just the opposite — are under appeal and are not expected to reach the Supreme Court for at least another year.

Enter Riley and Wurie, with cases that at first blush seem worlds removed from Snowden, Greenwald and the NSA.

On Aug. 2, 2009, members of a San Diego street gang called the Lincoln Park Bloods, who were standing by a red Oldsmobile owned by Riley, opened fire on a vehicle operated by a member of the rival Crips. Three weeks later, a San Diego police officer on routine patrol stopped Riley for driving another car, a Lexus, with expired registration tags. After confirming that Riley had a suspended license, the officer decided to impound the Lexus and radioed for backup to conduct an inventory of the car. Soon after, two handguns were found under the vehicle’s hood, and Riley was hauled off to jail.

Along with the firearms, the police seized Riley’s Samsung smartphone. At the station, officers twice examined the contents of the phone without a warrant, discovering stored photos of Riley standing next to the red Oldsmobile and videos showing him flashing what the cops considered to be gang signs. Later still, the police obtained Riley’s cellphone call log, which showed that his Samsung had been used at the scene of the shooting.Together with ballistic evidence linking the handguns to the shooting, the cellphone data helped convict Riley of attempted murder and assault with a semiautomatic weapon. He was sentenced to prison for 15 years to life. Both the trial court and the California Court of Appeal upheld the inventory of his cellphone as a search incident to an arrest, which courts in other contexts have long approved.

Wurie, on the other hand, was arrested in 2007 for dealing crack cocaine in the Andrew Square area of South Boston. While in custody, he kept getting calls on an old flip phone, which the police had confiscated, from a number identified on the phone’s screen as “my house.”

Officers opened the phone and probed its call logs without a warrant. Using a reverse directory to trace the number displayed, they discovered where Wurie lived. A search of the residence turned up a cache of crack, marijuana, a loaded Smith & Wesson 9 mm firearm and a supply of hollow-point ammunition.

Because of his history of violent crime dating back to 1996, Wurie was prosecuted in federal court as an Armed Career Criminal. He was convicted on three counts of drug dealing and illegal weapons possession in 2010 and was sentenced to 262 months in prison.

Unlike Riley, however, Wurie had better luck on appeal as the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated his conviction on two of the counts, ruling in a 2 to 1 decision that the search of his cellphone without probable cause could not be justified as a routine jailhouse inventory since the phone presented no danger to the police and there were no emergencies to excuse law enforcement from the obligation to obtain a warrant before exploring the device’s data. Noting that over 85 percent of the population owns a cellphone, the court observed that people keep the most vital personal information on their phones, ranging from medical records to financial data — information they believe will remain private absent a warrant and probable cause.

The lone dissenter in the case — Judge Jeffrey Howard, appointed to the bench by President George W. Bush — voted to uphold the cellphone search not only as a valid investigation after Wurie’s arrest, but because Wurie had no reasonable expectation of privacy in his call records pursuant to Smith v. Maryland. In January, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Obama Justice Department’s appeal in the Wurie case, along with Riley’s petition.

Normally, the last thing we would expect from the Roberts court is a robust defense of civil liberties, let alone a ruling that might enhance the prospects of an eventual direct challenge to the NSA’s metadata program. Still, judging from the tenor of Tuesday’s oral argument, we could be in for some surprises, as the panel appeared to be looking for a compromise that would recognize the privacy interests of cellphone owners without hampering legitimate criminal investigations.

While conservative Justice Samuel Alito invoked the specter of the Smith decision during the Wurie proceeding, asking if “the owner of a cell phone has a reasonable expectation of privacy in the [phone’s] call log,” liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg countered that “the real question is whether [the police] can search” a phone “without a warrant.” And not to be outdone, the court’s sometimes swing vote, Justice Anthony Kennedy, declared in the Riley hearing that the most pressing issue was whether there was “some standard where” the court “could draw the line” between what the law permits and what it disallows.

Whether any meaningful compromise is possible remains to be seen. Earlier this week, the high court showed its ideological colors again when it declined to hear a petition filed by Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges, Pentagon Papers whistle-blower Daniel Ellsberg, professor Noam Chomsky and others contesting the indefinite detention provisions of the National Defense Authorization Act. Given that unfortunate development, and the court’s dismal overall record to date as a guardian of the surveillance state, even a small step forward in Riley’s and Wurie’s appeals on behalf of informational privacy would come as a welcome relief.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.