The GM Strikes Set the Stage for a Nationwide Workers’ Revolt

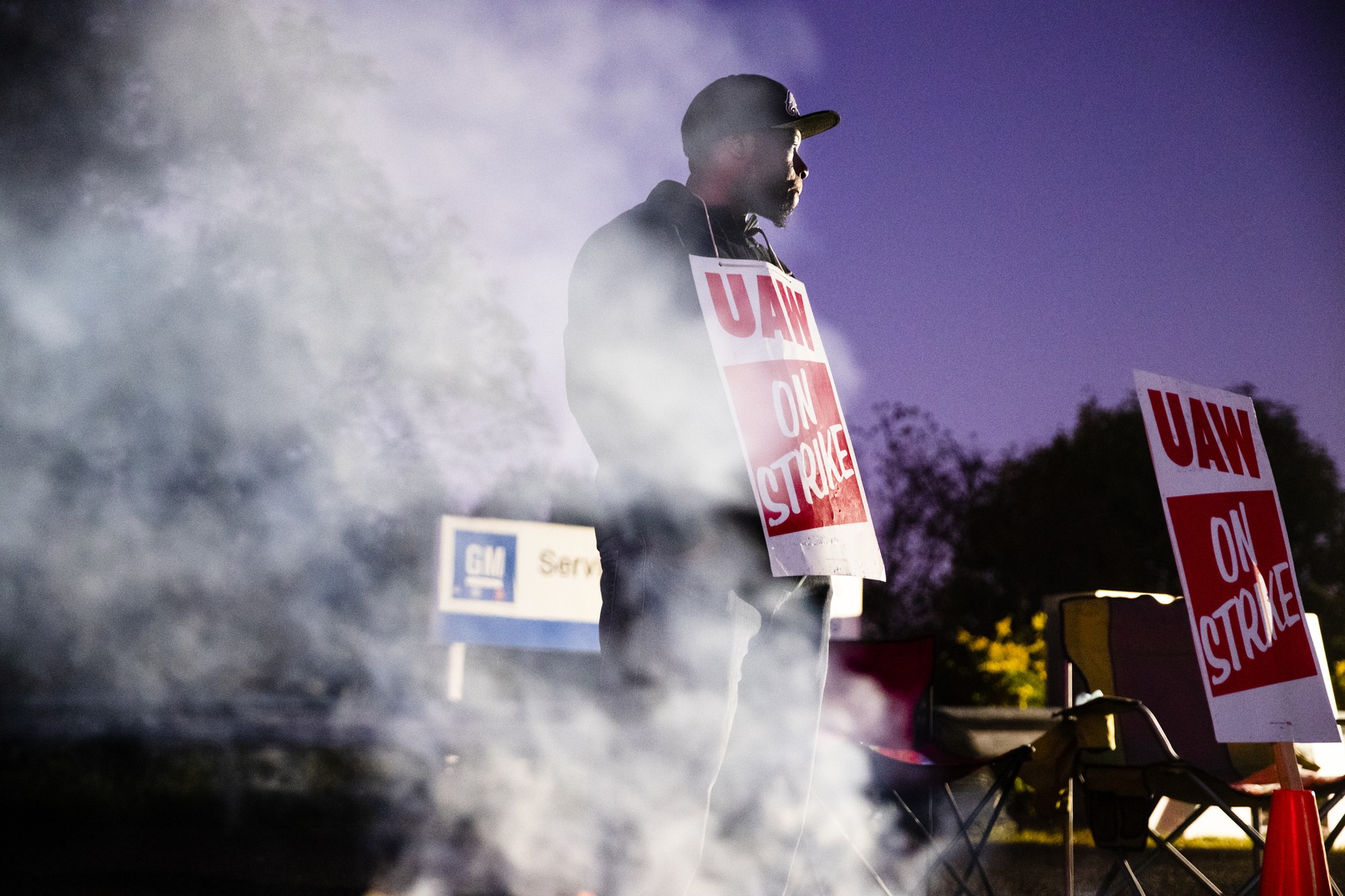

October’s Truthdiggers didn’t just obtain better conditions with their historic 41-day walkout; they set an example for all U.S. workers. Worker Omar Glover pickets outside a General Motors facility in Langhorne, Pa. (Matt Rourke / AP)

Worker Omar Glover pickets outside a General Motors facility in Langhorne, Pa. (Matt Rourke / AP)

Signs of a resurgent American labor movement are all around us, with no better example than the 40-day General Motors strike that began Sept. 16 and lasted well through October. While GM recovered after filing for bankruptcy in 2009, with the help of its workers and government bailouts, many of the American company’s employees have not felt the impact despite a booming economy.

After the 2008 financial crisis, autoworkers allowed adjustments to their contracts to help the automotive company get back on its proverbial feet, including “pay caps, a two-tier pay scale and [allowing] GM to hire temporary workers who wouldn’t have job security or benefits.” A decade later, to signal that they have grown tired over working conditions that do not reflect the company’s billions in profits, 49,000 autoworkers in GM plants across the U.S. went on a strike led by the United Auto Workers (UAW) union. The walkout became the largest and longest strike at the auto giant in several decades.

As labor reporter Steven Greenhouse told Amy Goodman on DemocracyNow! during the protests, “The workers are saying, you know, ‘What gives? We, the workers, we, the U.S. taxpayers, saved GM. So why is it closing important plants in the U.S., like the Lordstown plant [in Ohio], while keeping plants running in Mexico that make the same thing?’ So, they just — I think it’s basically a sense of … ‘We helped you. We went the extra mile for you, GM. And now we want you to be fair to us.’ It’s really a strike over fairness and being treated with the respect they feel that they deserve.”

According to UAW, GM wages have not kept up with inflation, but last year it gave its CEO, Mary Barra, a whopping $22 million, while also being exempt from paying federal taxes. Planned plant closures in the U.S., proposed changes in their health care plans and an ever-increasing number of temp workers also added to autoworkers’ many grievances. The protests made headlines all over, with many labor activists showing their solidarity with the historic walkout. Several 2020 Democratic presidential hopefuls such as Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden also showed their support, with all three frontrunners, among others, joining the picket line.

So what did the strikers win on Oct. 25 after weeks of a walkout that had many of them dipping into their own savings to get by? In short, a lot, according to the Guardian:

“They did pretty well,” said Kristin Dziczek, vice president of industry, labor and economics at the Center for Automotive Research, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. “They got more money. They got a pathway to regular employment for temporary workers. They defended their health care” when GM was seeking to sharply increase the premiums the United Automobile Workers (UAW) members paid.

The GM workers also received an $11,000 signing bonus, and the automaker agreed to essentially end its two-tier wage system by folding the lower tier into the top tier within four years. All those workers, lower-tier and top, will earn $32 an hour at contract’s end – some lower-tier workers now earning less than $20 an hour.

Dziczek added that the UAW failed to win any additional job security measures and failed to achieve one of its primary goals: reopening an assembly plant in Lordstown, Ohio. The union did, however, persuade GM to reverse plans to close its Detroit-Hamtramck plant, which had been scheduled to close in January. GM plans to invest $3 billion in overhauling that plant.

This, however, isn’t the first (and most likely not the last) time that GM employees used protests to negotiate with their employer. A piece in Jacobin tells the story of the first time, in 1936, GM workers went on strike to protest dire labor conditions.

Back in 1936, workers at GM’s plants in Flint, Michigan had it rough. They were subject to constant speedups in production, taking a toll on their bodies and spirits. … The average worker was taking home about $900, about half of what the federal government determined was necessary to provide for a family of four that year. Rather than pay their workers adequate wages, GM spent money on detectives hired to spy on workers and root out union organizers. The company also conscripted the Black Legion — a right-wing vigilante group that had broken from the KKK and counted as its enemies Jews, Catholics, blacks, and labor unions — to intimidate troublemaking workers. (This wasn’t GM’s only tie to fascists: in 1935, it supplied the Third Reich with military vehicles.)

The newly minted UAW took note of the dissatisfaction in Flint, and seized the opportunity and began organizing workers into the union.

While the labor movement was weakened in subsequent years, most notably under President Ronald Reagan who sought to break up unions, in recent years as unemployment has plummeted and the U.S. economy surged, workers are becoming increasingly conscious of the inequality plaguing the nation as corporate bosses reap the great majority of the benefits of their labor. The GM strike is only one of many strikes that have been taking place across the U.S. in recent years, including teachers and fast-food workers in states like Illinois, Kansas, Ohio and more.

With their recent strike, GM workers not only obtained better work contracts for themselves while setting the tone for negotiations throughout the auto industry, they also set an example for other American workers struggling against the same issues they faced. For continuing the rekindling of the U.S. labor movement through their activism and setting the stage for a nationwide workers’ revolt, the GM strikers are our Truthdiggers of the month.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.