China Bests U.S. on the Factory Floor in Obamas’ Netflix Debut

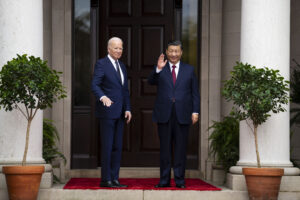

"American Factory" highlights the mismatched workforces to shattering effect at a Chinese auto glass factory in Dayton, Ohio. Chinese and American workers do their jobs side by side in "American Factory." (Netflix)

Chinese and American workers do their jobs side by side in "American Factory." (Netflix)

The Obamas’ first Netflix release, “American Factory,” available beginning Wednesday on the streaming service and in select theaters, arrives at a time when most concede Chinese economic hegemony will eventually usurp that of the U.S.

The subject of the film, which won the best director award at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, is a former General Motors factory in Dayton, Ohio, purchased and refitted by the Chinese company Fuyao Glass, one of the largest auto glassmakers in the world.

“There are two crisscrossing entities: One is the rise and stability of middle-income wealth in China and the decline of the very same thing in the Midwest” United States, said co-director Steven Bognar, who again teams with longtime partner, Julia Reichert. Their work includes the 2008 Oscar nominee “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant,” an HBO short that documents the closing of the factory that is now reopened and the subject of their latest film.

“American Factory” is the first film by Higher Ground, the production entity formed by former President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama, who met with the filmmakers.

“I think they’re great believers in the importance of storytelling, and they’re great believers in telling the story of everyday Americans,” Reichert said. “They’re both from humble beginnings and so are we. So, the perspective we bring as working-class people, they appreciated that.”

Bognar and Reichert have lived in Dayton for decades and can recall when a blue-collar middle class thrived there. Under GM, factory workers were earning $29 to $32 per hour. “But that’s gone now. And Fuyao, at $14 per hour, that’s still one of the best jobs you can get in Dayton,” said Reichert, as wages have lagged behind cost-of-living increases for decades.

The movie begins at the opening of the Fuyao Glass factory in 2015. Goodwill abounds though it is slow going at first, as many of the workers have to learn the delicate technique behind glassmaking to often shattering effect and both Chinese and American employees must navigate language and cultural differences. On off days, some go fishing together, and others share a Thanksgiving meal.

As the factory falls behind on its quota, company founder and Chairman Cao Dewang arrives from China to get a firsthand look at the operation. The son of a successful salesman who was sent down during the Cultural Revolution, Cao was raised mostly in poverty, selling cigarettes as a child. But after the death of Chairman Mao Zedong in 1976, Cao took advantage of the country’s new open policies and became a successful entrepreneur; today he has factories in 15 countries.

At the Dayton factory, cracks begin to emerge between Chinese and American workers and, in a meeting of Chinese employees only, bosses assure staff that in dealing with Americans, “Donkeys like being petted in the direction of their coat.” Later we are told the reason the newly trained American workers can’t perform as quickly as their experienced Chinese counterparts is because “they are slow. They have fat fingers.”

Co-director Reichert said she “couldn’t cite something more specific” about the level of racism at play. “There was nationalism, definitely, and that rallied the workers to work harder and put in more hours. We experience nationalism here, too. It keeps working people apart—‘The American workers aren’t as good, these Chinese workers are kind of weird’—you appeal to nationalism on both sides.”

As a way to improve matters, American workers are invited to the Fuyao factory in Fujian, China—an example of what is expected from those in Dayton. In addition to touring the plant, the U.S. workers are treated to a bizarre performance as Chinese factory employees sing songs written by their boss Cao, as well as a group wedding of younger workers. In a conversation with his American counterpart, one Chinese supervisor scoffs, “Only eight hours a day, that’s an easy life.” The workers in China, we’re told, work 12-hour days with two days off per month.

Chinese factories usually turn a profit in their first year and with the Dayton factory falling short, heads begin to roll, starting with top brass like Vice President Dave Burrows. According to the filmmakers, turnover has been close to 6,000 to date at the factory in its five years of operation.

“People are fired not just for being pro union, but because management feels they’re not doing a good enough job and they’re not working fast enough,” Bognar said. “There were periods where people were getting fired every day and they were hiring a lot of people.”

A significant portion of the movie covers an effort to unionize the factory, a move Cao vehemently opposes. In response, management hires a union avoidance consultant, which sets up mandatory anti-union lectures for employees.

“Chinese management had to be taught how to fight the union; that was not something they brought over here,” said Reichert about union busters. “They intimidate people, confuse people. There were a lot of firings of people who showed activism for the union. That is illegal. That kind of thing also happens in American factories. I hope it doesn’t come across as the Chinese trying to keep the workers down. They learned that from the Americans.”

Last month, the U.S. Department of Labor announced nearly $725,000 in OSHA penalties against Fuyao. “Everyone says they believe in safety, but safe doesn’t pay the bills,” says company safety manager John Crane, who later resigns in the film. In December 2017, an employee was crushed to death after cutting an attached strap from a pallet of glass sheets that weighed nearly 2,000 pounds.

“The Chinese management folks weren’t really that aware of U.S. labor laws or OSHA or EPA,” Reichert said. “In China, one of the skills of being a great manager, or owner, is getting around laws like this. And by the way, that’s true here. A lot of big companies accept OSHA fines because they really aren’t that much.

In “American Factory,” we learn the Fuyao plant in Dayton has been turning a profit since last year. But in the film’s final scenes, we see Cao touring the factory floor, reviewing new equipment, automation that will relieve the stress of repetitive motion and, in some cases, workers of their jobs. A recent Brookings Institution study showed that 25% of U.S. jobs will soon succumb to automation.

“The working class of America needs to be at the table, and that would be through their spokespeople,” Reichert said. “They should be at the table with the owners and the government.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.