History Holds the Antidote to Trump’s Fascist Politics

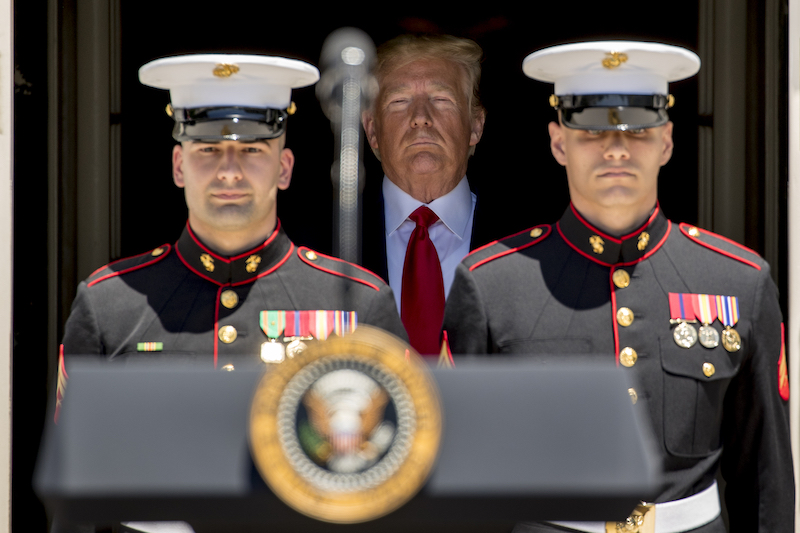

Americans’ refusal to learn about the past is leading them to revel in what they should be ashamed of and alarmed over. Andrew Harnik / AP

Andrew Harnik / AP

“[T]he great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.” —James Baldwin

America is in a state of crisis that touches every aspect of public life, extending from a crisis of economics produced by massive inequality to a crisis of ideas, agency, memory and politics, aided and abetted by controlling apparatuses that induce ubiquitous forms of historical amnesia. We are in a new historical period, one in which everything is transformed and corrupted by the neoliberal tools of financialization, deregulation and austerity. Within this new nexus of power, anti-democratic principles have become normalized, weakening society’s democratic defenses. Egregious degrees of exploitation and unchecked militarism are now matched by a politics of disposability and terminal exclusion, in which human beings are viewed as the embodiment of human waste, reinforced, if not propelled, by an ethos of white nationalism and white supremacy. As historian Paul Gilroy has noted, the motion of history and the production of politics are now being read “through racialized categories.”

Fascist principles, or one version of what journalist Natasha Lennard calls microfascism, now operate at so many levels of everyday society that it is difficult to recognize them, especially as they have the imprimatur of the president of the United States. Fascist practices and desires work through diverse social media platforms and mainstream and right-wing cultural apparatuses in multiple ways. They largely function ideologically and politically to objectify people, promote spectacles of violence, endorse consumerism as the only viable way of life, legitimate a murderous nationalism, construct psychological borders in people’s minds in order to privilege certain groups, promote mindlessness through the ubiquity of celebrity culture, normalize the discourse of hate in everyday exchanges, and produce endless “practices of authoritarianism and domination and exploitation that form us.” In the fog of social and historical amnesia, moral boundaries disappear, people become more accepting of extreme acts of cruelty and the propaganda machines that create alternative thoughts, and view any viable critique of power as fake news, all the while disconnecting toxic language and policies from their social costs. Writer Fintan O’Toole may be right in arguing that such actions constitute a trial run for fascism:

Fascism doesn’t arise suddenly in an existing democracy. It is not easy to get people to give up their ideas of freedom and civility. You have to do trial runs that, if they are done well, serve two purposes. They get people used to something they may initially recoil from; and they allow you to refine and calibrate. This is what is happening now and we would be fools not to see it.

Under the reign of neoliberalism, the dark plague of fascism engulfs American society as the history of concentration camps disappear, the killing of intellectuals is forgotten and the terror of fascist violence evaporates in the spectacles of violence accompanied by anti-intellectual blabber and a rampant culture of forgetting. What must be remembered here is that we are not only moral and political subjects, but also historical subjects capable of both understanding and changing the world. And it is precisely this relationship between historical consciousness and political action that points to new possibilities for change. And while historical consciousness can be both informative and emancipatory, it can also lead to “malicious interpretations of the present,” as well as elements of history that are difficult to accept. At the same time, historical awareness can uncover dangerous memories and narratives of those whose voices have been drowned out by those who have the power to write history to serve their narrow and reactionary interests. It is precisely in the use of “critical” history to offer the resources to challenge the ideological, educational and militant tools deployed by emerging right-wing and fascist groups that their toxic use of history and the present can be challenged. In this instance, any radical social movement needs a historically informed notion of struggle that is solidly on the side of a strong anti-capitalist movement. Resistance is no longer an option, given that both the humanity and the life of the planet are at stake.

American society has turned lethal, as is evident in its assaults upon poor children, undocumented immigrants and those considered disposable by virtue of their race, ethnicity, religion and color. In an age when historical memory either disappears or is rewritten in the language of erasure and misrepresentation, too many people look away and become complicitous with diverse forms of fascism emerging across the globe. Regimes of fear destroy standards of truth, creating easy paths for warmongers, racists, misogynists and nativists to take advantage of a comatose public. Neoliberal fascism, a new social and political formation that combines the savage consequences of economic inequality and a politics of survival with the dictates of ultranationalism and white supremacy, took hold in the 1970s and has become a powerful engine of violence and cruelty, both in the United States and in an increasing number of other countries. Neoliberal fascism is the enemy of revisionist forms of history, because it disdains any resource that can be used to hold power accountable and translate past events into a form of moral witnessing in the present.

In its upgraded forms, any viable resistance to fascism needs new narratives, a new understanding of politics, power and resistance in order to counter violence and state terrorism while reviving historical memory as a forum for critically interrogating the unsettling and unspeakable, as well as a critical engagement with a culture of real, visceral and symbolic violence. Politics here takes on an ethical necessity and ambition. Most importantly, we need a politics in which education becomes central, a politics in which it is recognized that the populist moment in the service of neoliberal capitalism is, at its core, a crisis of identity, memory and agency, if not democracy itself. As capital is liberated from all constraints, historical memory and the institutions that support it wither, along with the democratic ideals of equality, popular sovereignty and the freedom from basic social needs. Scholar Nancy Fraser has argued that the upsurge of populism in the United States is partly fueled by a revolt against the political elites, the false promises of liberal democracy, and “blockages” caused by neoliberal modes of governance. She writes:

In the United States, those blockages include the metastasization of finance; the proliferation of precarious service-sector McJobs; ballooning consumer debt to enable the purchase of cheap stuff produced elsewhere; conjoint increases in carbon emissions, extreme weather, and climate denialism; racialized mass incarceration and systemic police violence; and mounting stresses on family and community life thanks in part to lengthened working hours and diminished social supports. Together, these forces have been grinding away at our social order for quite some time without producing a political earthquake. Now, however, all bets are off. In today’s widespread rejection of politics as usual, an objective system wide crisis has found its subjective political voice. The political strand of our general crisis is a crisis of hegemony.

In this instance, populism emerges as a form of politics in which any gesture toward giving a real voice and power to people is substituted for the power of demagogues who claim to speak on their behalf. Right-wing populism begins as a revolt against a neoliberal winner-take-all society and is quickly appropriated by demagogues such as Donald Trump to address a mix of economic anxiety, existential uncertainty and the fear of undocumented immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Instead of learning from a past filled with genocidal wars waged in the name of difference, the emerging fascist tyrants have enshrined a form of unlearning that privileges moral comas and recounts endless narratives of hate that vilify immigrants, refugees and undocumented children as chosen enemies of the paragons of racial cleansing.

Something sinister and horrifying is happening to alleged liberal democracies all over the globe. Democratic institutions such as the independent media, schools, the legal system, the welfare state and public and higher education are under siege worldwide. Public media are underfunded, schools are privatized or modeled after prisons, the funds for social provisions disappear as military budgets balloon, and the legal system is increasingly positioned as an engine of racial discrimination and the default institution for criminalizing a range of behaviors. The echoes of a fascist past are with us once again, resurrecting the discourses of hatred, exclusion and ultranationalism in countries such as the United States, Hungary, Brazil, Poland, Turkey and the Philippines. Right-wing extremist parties have infused a fascist ideology with new energy through an apocalyptic populism that constructs the nation through a series of racist and nativist exclusions, all the while feeding off the chaos produced by the dynamics of neoliberalism. Under such circumstances, the promises of a liberal democracy are receding as present-day reactionaries work to subvert language, values, civic courage, history and a critical consciousness. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, for instance, has pledged to rid his country’s educational system of all references to the work of radical educator Paulo Freire. In the United States, Trump accelerates his work on public and higher education by cutting budgets and appointing Betsy DeVos, a billionaire and sworn enemy of public education and advocate of school choice and charter schools, as the secretary of education. In addition, education in many parts of the globe has increasingly become a tool of domination, as market fundamentalists and reactionary politicians imprison intellectuals, close down schools, undercut progressive curriculum, attack teacher unions and impose pedagogies of repression, often killing the imaginative and creative capacities of students while turning public schools into a conveyer belt that propels students marginalized by class and color into a life of poverty or worse—the criminal justice system and prison.

We live at a time in which two worlds are colliding. First, there is the world of neoliberal globalization, which is in crisis mode because it can no longer deliver on its promises or contain its own ruthlessness. Hence, there is a worldwide revolt against global capitalism that operates mostly to fuel forms of right-wing populism and a systemic war on democracy itself. Power is now enamored with amassing profits and capital and is increasingly addicted to a politics of social sorting and racial cleansing. Second, there is a genuine series of democratic revolts and struggles, which is growing, especially among young people, and is rewriting and revising an updated script for democratic socialism, a script that can both challenge the neoliberal world of finance capital while rethinking the meaning of politics, if not democracy itself.

What is not in doubt is that all across the world, the global thrust toward democratization that emerged after World War II is giving way, once again, to tyrannies. As alarming as the signs may be, the public cannot ignore or allow a fascist politics to take root in the United States. Such a threat has been exacerbated as a mode of consciousness and at a time when academic discipline has lost favor with the American public. One consequence is that historical consciousness has been replaced by a form of social and historical amnesia. No longer a required course in most institutions of higher education, history in its various registers and genealogies has declined into near oblivion at a time when forms of public knowledge and civic literacy have accelerated exponentially. Moreover, “fewer than 2 percent of male undergraduates and fewer than 1 percent of females major in history, compared with more than 6 percent and nearly 5 percent, respectively in the late 1960s.” Some colleges have threated to abolish their history departments. Ironically, this is happening at a time when an increasing number of Americans are ignorant of the past, making them vulnerable to the simplistic appeals of demagogues. Ignorance has lost its innocence and is no longer synonymous with the absence of knowledge. It has become malicious in its refusal to know, to disdain criticism, to undermine the value of historical consciousness, and to render invisible important issues that lie on the side of social and economic justice.

James Baldwin was right in issuing his stern warning in “No Name in the Street”: “Ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.” As is well known, Trump’s real and pretended ignorance lights up the Twitter landscape almost every day. He denies climate change, along with the dangers that it poses to humanity; he shuts down the government because he cannot get the funds for his border wall—a grotesque symbol of nativism; and he mangles history with his ignorance of the past. For instance, he once implied in a speech that Frederick Douglass is still alive and is only now getting the recognition he deserved. Trump’s ignorance is legendary, if not shameful, but what he models is dangerous, because presidential historical ignorance suggests that the problems suffering people face, they face alone. That is, in their social atomization and isolation, they are unaware that history’s great liberating force is that “having a sense of history is knowing that whatever happens to us or to our world we are not alone. It has happened in some form before.”

This lethal form of ignorance now fuses with a reckless use of state power that holds both human life and the planet hostage. Historian David Bright claims that Trump’s “ignorance of history, of policy, of political processes [and] the Constitution,” rather than his authoritarianism, is “the greatest threat to our democracy.” According to Bright, Trump’s grasp of history operates at a level of understanding one would expect from a fifth-grader or younger. However, there is more at stake here than the production of a toxic form of ignorance and the shrinking of historical horizons. Trump not only distorts history, but also makes it, and in doing so suggests a contempt for knowledge, which he manipulates for political purposes. Ignorance in high places is a boon to history deniers and legitimates the authoritarian assumption that history is only made by strong men. What we are witnessing is the corruption of politics, coupled with explicit expressions of cruelty and a “widely sanctioned ruthlessness.” How else to explain the current separation of children from their parents at the southern border in the United States, and the creation of internment centers that have been exposed as an assault on civil rights and human dignity?

It is hard to imagine a more urgent moment for making education central to politics. If we are going to develop a politics capable of awakening our critical, imaginative and historical sensibilities, it is crucial for educators and others to develop a collective language that rewrites the traditional notion of politics. Such a language is necessary to enable the conditions for a collective international resistance against Trump’s efforts to forge what Noam Chomsky calls a global reactionary alliance under the U.S. aegis, including the “illiberal democracies” of Eastern Europe and Brazil’s grotesque Bolsonaro. Such a movement is important in order to resist and overcome the tyrannical fascist nightmares that are descending upon the United States, Brazil and a number of other countries in Europe plagued by the rise of neo-Nazi parties. In an age when the only obligation of citizenship is shopping and a culture of compassion has given way to a culture of cruelty, it is all the more crucial to take seriously the notion that a democracy cannot exist or be defended without informed and critically engaged citizens.

Education, both in its symbolic and institutional forms, has a central role to play in fighting the resurgence of fascist cultures, mythic historical narratives and the emerging ideologies of white supremacy and white nationalism. Moreover, as fascists across the globe are disseminating toxic racist and ultranationalist images of the past, it is essential to reclaim education as a form of historical consciousness and moral witnessing. This is especially true at a time when historical and social amnesia have become a national pastime, particularly in the United States, matched only by the masculinization of the public sphere and the increasing normalization of a fascist politics that thrives on ignorance, fear, hatred and the suppression of dissent. Oppression is no longer defined simply through economic structures. A neoliberal culture of precarity and uncertainty has resulted in job insecurity, declining wages, the slashing of retirement funds and the weakening of the welfare state, all of which are largely addressed through right-wing cultural apparatuses that frame such conditions pedagogically as part of a broader politics of fear, hatred and bigotry. Education, particularly in the social media, operates with great influence as a sounding board for right-wing nihilism and white supremacy groups and has become a powerful portal for circulating fascist ideas, legitimating hate-fueled violence and promoting ugly racist rhetoric that undermines democratic ideals. Yet education is not simply about domination, and it reaches far beyond the classroom, and while often imperceptible, is crucial in using the new media to challenge and resist the rise of fascist pedagogical formations and their rehabilitation of fascist principles and ideas.

Against a numbing indifference, despair and withdrawal into the private orbits of the isolated self, there is a need to create those formative cultures that are humanizing, foster the capacity to hear others, sustain complex thoughts and engage in solving social problems. We have no other choice if we are to resist the increasing destabilization of democratic institutions, the assault on reason, the collapse of the distinction between fact and fiction, and the taste for brutality that now spreads across a number of countries, including the U.S., like a plague. The pedagogical lesson here is that fascism begins with hateful words and the demonization of others considered disposable, and moves to an attack on ideas, the burning of books, the disappearance of intellectuals and the emergence of the carceral state and the horrors of detention jails and camps. As historian Jon Nixon suggests, pedagogy as a form of critical education “provides us with a protected space within which to think against the grain of received opinion: a space to question and challenge, to imagine the world from different standpoints and perspectives, to reflect upon ourselves in relation to others and, in so doing, to understand what it means to ‘assume responsibility.'”

This is even more reason for educators and others to address important social issues and defend public and higher education as democratic public spheres. It is all the more reason to defend the teaching of history as a protected space within which to teach students to think against the grain, hold power accountable, embrace a sense of citizenship and civic courage, and to “learn about the world beyond the confines of their home towns, and to try to understand where they might fit in.” We live in a world in which everything is now privatized, transformed into what authors Michael Silk and David Andrews call “spectacular spaces of consumption” and subject to the vicissitudes of the military-security state, all the while accompanied by the rise of a fascist politics rooted in the mobilizing passions of ultranationalism, racism and an apocalyptic populism. One consequence is the emergence of what the late historian Tony Judt called an “eviscerated society”—“one that is stripped of the thick mesh of mutual obligations and social responsibilities to be found” in any viable democracy. This grim reality has been called a “failed sociality”—a failure in the power of the civic imagination, political will and the promises of a radical democracy. It is also part of a politics that strips the social of any democratic ideals.

Trump’s presidency may only be symptomatic of the long decline of liberal democracy in the United States into a corrupt political and economic oligarchy, but its presence signifies one of the gravest challenges, if not dangers, the country has faced in over a century. A formative culture of lies, ignorance, corruption and violence is now fueled by a range of orthodoxies shaping American life, including social conservatism, market fundamentalism, apocalyptic nationalism, religious extremism and unchecked racism—all of which occupy the centers of power at the highest levels of government. Historical memory and moral witnessing have given way to a bankrupt nostalgia that celebrates the most regressive moments in U.S. history.

Fantasies of absolute control, racial cleansing, unchecked militarism and class warfare are at the heart of a U.S. social order that has turned lethal, evident in the militarizing of schools and public spaces and the centrality of a war culture as an organized mode of governance. This is a dystopian social order marked by hollow words, an imagination pillaged of any substantive meaning, cleansed of compassion and used to legitimate the notion that alternative worlds are impossible to entertain. What we are witnessing is an abandonment of democratic institutions, however flawed, coupled with a full-scale attack on dissent, thoughtful reasoning and the social imagination. Trump has degraded the office of the president and has elevated the ethos of political corruption, hypermasculinity and lying to a level that leaves many people numb and exhausted. He has normalized the unthinkable, legitimated the inexcusable and defended the indefensible. Under such circumstances, the United States is moving into the dark shadows of a present that bears a horrifying resemblance to an earlier period of fascism with its language of racial purification, hatred of dissent, systemic violence, intolerance and the Trump’s administration’s “glorification of aggressive and violent solutions to complex social problems.”

The history of fascism offers an early warning system and teaches us that language, which operates in the service of violence, desperation and the troubled landscapes of hatred, carries the potential for resurrecting the darkest moments of history. It erodes our humanity and makes many people numb and silent under the glare of ideologies and practices that mimic and legitimate hideous and atrocious acts. This is a language that eliminates the space of plurality, glorifies walls and borders, hates differences that do not mimic a white public sphere, and makes vulnerable populations—even poor young children—superfluous as human beings. Trump’s language, like that which characterized older fascist regimes, mutilates contemporary politics, disdains empathy and serious moral and political criticism, and makes it more difficult to criticize dominant relations of power. His toxic language also fuels the rhetoric of war, a supercharged masculinity, the rise of public anti-intellectuals and a resurgent white supremacy. However, this shift toward a fascist politics cannot be laid exclusively at Trump’s feet. The language of putrid values of a nascent fascism have been brewing in the United States for some time. It is a language that is comfortable viewing the world as a combat zone, a world that exists to be plundered, and one that views those deemed different because of their class, race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation as a threat to be feared, if not eliminated. When Trump uses a toxic rhetoric that portrays undocumented immigrants as criminals, rapists and drug dealers, he is doing more than using ugly epithets—he is also materializing such discourse into policies that rip children from their mother’s arms, put the lives of immigrants at risk and impose cruel and inhumane practices that assault the body, mind and human dignity.

While it is fruitless to believe that there is perfect mirror for measuring a resurgent fascism, it is crucial to recognize how the crystalized elements of an updated fascism have emerged in new forms in the shape of a U.S.-style authoritarianism. Yet, too many intellectuals, historians and media pundits deny the presence of fascist politics in the United States. In part, this may be because history is written by the winners, but also because a form of serious historical analysis operates from a weak position in a culture of instant gratification and immediacy propelled by the need for instant pleasure. In the age of selfies and tweet storms, time is reduced to short bursts of attention as the slowing down of time necessary for focused analytical thought and imaginative contemplation withers. Author Leon Wieseltier is on target in arguing that we live in an era in which “words cannot wait for thoughts [and] patience is a … liability.” In the current age of instant gratification, history has become a burden, treated like a discarded relic that no longer deserves respect. The past is now either too dangerous to contemplate, relegated to the abyss of willful ignorance, or rewritten and appropriated in the interests of the anti-democratic forces of ultranationalism, nativism and social Darwinism, as is taking place in countries such as Poland and Hungary. However frightening and seemingly impossible in a liberal democracy, neither history nor the obvious signs of a fascist politics can be easily dismissed, especially with the claim that demagogues such as Trump have not created concentration camps or engineered plans for genocidal acts. Echoes of a fascist past are strikingly evident in degrading and inhumane conditions in the migrant detention sites, many of which hold children as young as 5 months old.

According to the Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the conditions in the detention centers holding immigrants and refugees were “undignified” and “alarming.” Her accusations were confirmed by a Department of Homeland Security report on detention centers on the southern border:

[P]oor conditions include overcrowding, flu outbreaks, and lack of clean clothing. The report also detailed horrific incidents—such as overuse of solitary confinement, and reports of nooses in detainee cells—that signal violations of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention standards and infringements on detainee rights.

It gets worse, especially in regard to the caging of children in prisonlike detention centers. The New York Times has reported that many of the children are suffering from hunger, are housed in cramped cinder-block cells with only one toilet, are sleeping on cement floors and are subject to a number of illnesses, including scabies, shingles and chicken pox. According to the Times, lawyers who visited the Clint, Texas, detention center described seeing:

… children in filthy clothes, often lacking diapers and with no access to toothbrushes, toothpaste, or soap. … Warren Binford, director of the clinical law program in Willamette University in Oregon, said that in all her years of visiting detention and shelter facilities, she had never encountered conditions so bad—351 children crammed into what she described as [a] prisonlike environment.

Fascist politics, in its more recent, updated capitalist formation, has a long history of covering up its crimes against humanity, especially the most egregious acts of genocide. Trump and his top immigration officials may not be perpetuating overt acts of genocide with his nativist policies and acts of unimaginable cruelty in incarcerating immigrants, especially children. Nevertheless, he is following a fascist script in denying “reports that migrant children were being held in horrific conditions in federal detention facilities,” even as the accounts of disease, hunger and overcrowding have multiplied in recent days. Moreover, like his counterparts in NATO and the EU, there is silence about who creates these refugee populations across the globe. Lying in the service of egregious forms of evil has a long history among demagogues. What is different with Trump is that he lies even in the face of irrefutable evidence to the contrary. In this instance, Trump’s lies and attempted cover-ups function as a form of depoliticization. That is, lying performs as a tool of power, promoting forms of manufactured ignorance in which it becomes difficult for the public to separate fact from fiction in order to recognize the violence and injustices imposed by the Trump administration on those populations it considers disposable. Given Trump’s embrace of an upgraded version of Hannah Arendt’s notions of thoughtlessness, cruelty and the banality of evil as central elements of totalitarianism, it is difficult to argue that fascism is a relic of the past.

Simply because the Trump administration may not be replicating in an exact fashion the sordid practices of violence and genocide reminiscent of fascist states in the 1930s does not mean that it has no resemblance to such a history. In fact, the legacy of fascism becomes even more important at a time when the language, policies and authoritarian ideology of the Trump administration echo a dangerous warning from history that cannot be ignored. Fascism does not disappear because it does not surface as a mirror image of the past. Fascism is not static, and the protean elements of fascism always run the risk of crystallizing into new forms. Fascism in its contemporary forms is a particular response to a range of capitalist crises that include the rise of massive inequality, a culture of fear, precarious employment, ruthless austerity policies that destroy the social contract, the rise of the carceral state and the erosion of white privilege, among other issues.

Fascism is also obvious by its hatred of the public good, by what author Toni Morrison calls its “desire to purge democracy of all of its ideals,” and by its willingness to privilege power over human needs and render racial difference as an organizing principle of society. The ghosts of fascism should terrify us, but most importantly, the horrors of the past should educate us and imbue us with a spirit of civic justice and collective courage in the fight for a substantive and inclusive democracy. What must be remembered in this time of tyranny is that historical consciousness is a crucial tool for unraveling the layers of meaning, suffering, the search for community, the overcoming of despair and the momentum of dramatic change, however unpleasant this may be at times. No act of the past can be deemed too horrible or hideous to contemplate if we are going to enlarge scope of our imaginations and the reach of social justice, both of which might prevent us from looking away, indifferent to the suffering around us. This suggests the need for rethinking the importance of historical memory, civic literacy and critical pedagogy as central to an informed and critical mode of agency. Rather than dismiss the notion that the organizing principles and fluctuating elements of fascism are still with us, a more appropriate response to Trump’s rise to power is to raise questions about what elements of his government signal the emergence of a fascism suited to a contemporary and distinctively updated political, economic and cultural landscape.

In an age when memory is under attack, civic literacy and a critical reading of history become both a source of hope and a tool of resistance. If reading history and critical forms of education are central to creating informed citizens, it is fundamental for educators to connect the past to the present and to view the present as a window into those horrors of the past that must never be repeated. A critical reading and teaching of history provides educators with a vital resource that helps inform the ethical ground for resistance—an antidote to Trump’s politics of disinformation, division, diversion and fragmentation. Moreover, memory as a form of critical consciousness is crucial in developing a form of historical and social responsibility that can work to offset a willful ignorance that provides the necessary conditions that both enable and reinforce a fascist politics. In the face of this nightmare, thinking and judging must be connected to our actions. At the very least, as scholar Angela Davis points out, learning to think critically about power, politics and economics while developing a robust historical consciousness provides the opportunity and space for people to say no and refuse “to settle for fast solutions, easy answers [and] formulaic resolutions.” In this instance, historical learning is not about constructing a linear narrative but about blasting history open, rupturing its silences, highlighting its detours, acknowledging the events of its transmission, and organizing its limits within a rigorous and compassionate engagement with human suffering, values and the legacy of the often unrepresentable or misrepresented.

We live at a time when the corruption of discourse has become a defining feature of politics, reinforced largely by an administration and a right-wing media apparatus that does not simply lie, but also works hard to eliminate the distinction between fantasy and fact. As Hannah Arendt has argued, at issue here is the creation of modes of agency that are complicit with fascist modes of governance. As she writes in “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi … but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exists.”

Under the reign of manic neoliberalism, time and attention have become a burden, subject to what philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls an “excess of stimuli, information, and impulses [and] radically changes the structure and economy of attention. Perception becomes fragmented and scattered.” The contemplative attention central to reading critically and listening attentively now give way to a hyperactive flow of information in which thinking is overcome by speed, compulsion, sound bites, fragments of information and a relentless stream of disruptions. As Han notes, there is a type of violence in which the fragmented mind undercuts the capacity to think dialectically, undermining the ability to make connections, imagine capaciously and develop comprehensive maps of meaning and politics. At work here is a form of pedagogy that depoliticizes and leaves individuals isolated, exhausted, ignorant of the forces that bear down on their lives, and susceptible to a highly charged culture of stimulation.

The terror of the unforeseen becomes ominous when history is used to hide rather than to illuminate the past, when it becomes difficult to translate private issues into larger systemic considerations, and people allow themselves to be both seduced and trapped into spectacles of violence, cruelty and authoritarian impulses. Reading the world critically and developing a historical consciousness are two important preconditions for intervening in the world. That is why critical reading and reading critically are so dangerous to Trump, his acolytes and those who hate democracy. Democracy as both an ideal and site of struggle can only survive with a public attentiveness to the power of history, politics and the rigor of informed judgments and thoughtful actions. It can only survive when we are willing to engage the power to think otherwise in order to act otherwise.

The never-ending crisis produced by neoliberalism, with its financial ruin for millions, its elimination of the welfare state, its deregulation of corporate power, its unchecked racism and its militarization of society, has to be matched by a crisis of ideas—in this case, one that embraces historical memory, rejects the normalization of fascist principles and opens a space for imagining that alternative worlds can be brought into being. While the long-term corrosion of politics and the emerging fascism in the U.S. will not end by simply learning how to read critically, the spaces opened by learning how to think critically create a bulwark against cynicism and foster a notion of hope that can be translated into forms of collective resistance. In the fascist script, historical memory becomes a liability, even dangerous, when it functions pedagogically to inform our political and social imagination. This is especially true when memory acts to identify forms of social injustice and enables critical reflection on the histories of repressed others. For instance, the haunting images of hungry, sick and frightened children in migrant detention centers do more than rupture the myth-making rhetoric of the American dream; they also invoke the revival of historical memories that tie the present to a fascist past. Moreover, critics who ignore such warnings by refusing to learn from the past reinforce Walter Lippmann’s warning a century ago, when he argued that “when a nation creates the conditions in which its citizens have little or no knowledge of past,” it is opening the door for them to “become victims of agitation and propaganda, subject to the appeals of quacks and charlatans.” In part, the merging of a willful ignorance and a willful refusal to learn from the past sets the stage for a right-wing populism eager to vent real existential anger in a hatred of others and a politics wedded to a politics of disposability and elimination.

Unsurprisingly, historical memory as a form of enlightenment and demystification is surely at odds with Trump’s use of history as a form of social amnesia and political camouflage. For instance, Trump’s 1930s slogan, “America First,” marks a regressive return to a time when nativism, misogyny and xenophobia defined the American experience. This inchoate nostalgia rewrites history in the warm glow and “belief in an essential American innocence, in the utter exceptionality, the ethical singularity and manifest destiny of the United States.” Philip Roth aptly characterizes this gratuitous form of nostalgia in his “American Pastoral” as the “undetonated past.” Innocence, in this script, is the stuff of mythologies that distort history and erase the political significance of moral witnessing and historical memory as a way of reading, translating and interrogating the past as it impacts, and sometimes explodes, the present.

Under Trump, both language and memory are disabled, emptied of substantive content, and the space of a shared reality crucial to any democracy is eviscerated. In this context, strict categories of identity cancel out notions of shared responsibilities and what might be termed a “more radical practice of citizenship.” History and language in this contemporary political script are paralyzed in the immediacy of tweeted experience, the thrill of the moment and the comfort of a cathartic emotional discharge. The danger, as history has taught us, is when words are systemically used to cover up lies and the capacity to think critically.

In such instances, the public spheres essential to a democracy wither and die, opening the door to fascist ideas, values and social relations: Trump, following in the footsteps of previous administrations, has sanctioned torture, ripped babies from their parents’ arms, imprisoned thousands of immigrant children, and declared the media, along with entire races and religions, to be the enemy of the American people. In doing so, he speaks to and legitimates a history in which state violence becomes an organizing principle of governance and, perversely, a potentially cathartic experience for his followers.

The corruption of language is often followed by the corruption of memory, morality and the eventual disappearance of books, ideas and human beings. Trump’s language of disappearance, dehumanization and censorship is an echo and erasure of the barbarism of another time. His regressive use of language and denial of history must be challenged so that the emancipatory energies and compelling narratives of resistance can be recalled in order to find new ways of challenging the ideologies and power relations that put them into play. Trump’s predatory use of language and public memory are part of a larger authoritarian politics of ethnic and racial cleansing that evokes the legacy of state violence that historically has been waged against those populations considered unknowable, unspeakable and disposable.

Indifferent to the historical footprints that mark expressions of state violence, the Trump administration uses historical amnesia as a weapon of (mis)education, power and politics, allowing public memory to wither and the architecture of fascism to go unchallenged. What is under siege now is the need to keep watch over the repressed narratives of memory and historical consciousness itself. The fight against a demagogic erasure of history must begin with an acute understanding that memory always makes a demand upon the present, refusing to accept ignorance as innocence.

As reality collapses into fake news, moral witnessing disappears into the hollow spectacles of right-wing media machines, and into state-sanctioned weaponry used to distort the truth, suppress dissent and attack the critical media. Trump uses Twitter as a public relations blitzkrieg to attack everyone—from his political enemies to celebrities—who has criticized him. He is particularly malignant in his racist attacks on black athletes, such as LeBron James, and black celebrities, such as CNN anchor Don Lemon. In this context, language no longer expands the reach of history, ethics and justice. On the contrary, it now operates in the service of slogans, bigotry and violence. Words are now turned into an undifferentiated mass of ashes, critical discourse reduced to rubble and informed judgments pushed to a distant, radioactive horizon.

Shouting replaces the pedagogical imperative to listen and reinforces the stories neoliberal fascism tells us about ourselves, our relations to others and the larger world. Under such circumstances, monstrous deeds are committed under the increasing normalization of civic and historical modes of illiteracy, if not ignorance. One consequence is that comparisons to the Nazi past can wither in the false belief that historical events are fixed in time and place and can only be repeated in history books. In an age marked by a war on terror, a culture of fear and the normalization of uncertainty, social amnesia has become a powerful tool for dismantling democracy. Indeed, in this age of forgetfulness, American society appears to revel in what it should be ashamed of and alarmed over.

Even with the insight of history, comparisons between the older orders of fascism and Trump’s regime of brutality, aggression and cruelty are considered by commentators to be too extreme. There is a cost to such caution: One is failing to learn the lessons of the past or, even worse, ignoring the past as a source of moral witnessing and resource for speaking for those no longer able to speak. Knowing how others in the past, such as those involved in the anti-war movement of the 1960s, successfully fought against elected demagogues such as Trump is crucial to a political strategy that reverses an impending global catastrophe.

The story of a fascist past needs to be retold, not to simply make comparisons to the present, though that is not an unworthy project, but to be able to imagine a new politics in which new knowledge will be built and, as Arendt states, “new insights … new knowledge … new memories, [and] new deeds, [will] take their point of departure.” This is not to suggest that history is a citadel of truth that can be easily mined. History offers no guarantees, and it can be used in the interest of violence as well as for emancipation.

Trump’s selective appropriation of history wages war on the past, celebrating rather than questioning fascist politics. Even more reason why, with the rise of fascist politics, there is a need for modes of historical inquiry and stories that challenge the distortions of the past, transcend private interests, and enable the American public to connect private issues to broader historical and political contexts. Comparing Trump’s ideology, policies and language to a fascist past offers the possibility to learn what is old and new in the dark times that have descended upon the Unites States. The pressing relevance of the 1930s is crucial to address how fascist ideas and practices originate and adapt to new conditions, and how people capitulate and resist them as well.

One of the central challenges to reclaiming history as an emancipatory discourse and critical field of study, among others, is how to recover the promise and possibilities of a democratic public life. Such a pedagogical task is viewed as dangerous to many people, because it provides the conditions for students and the wider public to exercise their intellectual capacities, embrace the ethical imagination, hold power accountable and embrace a sense of social responsibility. In fact, not surprisingly, a disconcerting number of academics and teachers in the current moment continue to join forces with right-wing politicians and conservative government agencies to argue that classrooms should be free of politics. Their shared conclusion? That schools should be spaces where matters of power, values and social justice should not be questioned. The scornful accusation in this case is that teachers who believe in civic education indoctrinate their students. Those who make this accusation suggest that it’s possible to exist in an ideologically pure and politically neutral world, where pedagogy can be merely a banal transmission of facts, in which nothing controversial is stated and teachers are forbidden to engage in critical thinking or utter one word related to any of the major problems facing society more broadly. It is hard to make this stuff up. In 2012, the Texas Republican Party platform stated a goal of banning critical thinking instruction throughout the state. These Republicans justified their plunge into enshrining ignorance and irrationality on the grounds that such thinking “undermines the student’s fixed beliefs” and is a “direct challenge to leaders and their claims on authority.” This is the same irrationality that has resulted, in many states, in the banning of hundreds of books from the school curriculum, including such dangerous texts as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “The Catcher in the Rye,” “Animal Farm” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

Of course, this view of education is as much a flight from reality as it is an instance of irresponsible pedagogy. In contrast, one useful approach to embracing the classroom as a political site while rejecting any form of indoctrination and censorship is for educators to think through what I have called elsewhere the distinction between a politicizing pedagogy, which insists wrongly that students think exactly as we do as educators, and a political pedagogy, which teaches students, through dialogue, about the importance of power, social responsibility and taking a stand (without standing still). Political pedagogy, unlike a dogmatic or indoctrinating pedagogy, embodies the principles of critical pedagogy through rigorously engaging the full range of ideas about an issue.

Political pedagogy attempts to teach students how to think critically and examine the relationship between authority and power and classroom knowledge and power, while learning the historical traditions, ideas, disciplines and issues that will enable them to fully exercise their political, social and economic rights as part of a broader register of active citizenship. Political education also encourages students to think and act critically in order to struggle for those political and economic conditions that make a democracy possible.

The emerging authoritarianism in many countries today raises questions about the role of education, teachers and students in a time of tyranny. How might we imagine education and the teaching of history as central to a politics whose task is, in part, to create a new language for students, one that is crucial to reviving a radical imagination, a notion of social hope, and the courage to undertake collective struggle? How might public and higher education and other cultural institutions address the deep, unchecked nihilism and despair of the current moment? How might educators be persuaded not to abandon democracy, and take seriously the need to create informed citizens capable of fighting the resurgence of a fascist politics? Fascism thrives on surveillance, arrest, crushing dissent, spreading lies, scapegoating those considered disposable and attacking any vestige of the truth. Fascism is the modern-day form of a depoliticizing machine that renders individual and collective agency incapable of exercising the conduct, sensibilities and practices endemic to a robust form of citizenship. When fascism is strong, democracy is not simply weak or under siege—the very institutions that inform and educate a public begin to disappear. As educational reformer John Dewey once noted that “democratic conditions do not automatically sustain themselves”—they can only survive in the midst of a critical and formative culture that “produces the habits and dispositions—in short—a culture to sustain it.”

Political science professor Melvin Rogers, reiterating Dewey’s warning, rightly argues that most critics of Trump are missing his crucial insights and how they apply to the refusal to normalize Trump’s fascist politics or rely too heavily on the false assumption that the country’s checks and balances and fundamental institutions by default will protect us from an impeding fascism. He writes:

Dewey’s worry is as urgent today as it was in 1939. Those who believe the strength of our institutions will win the day miss the slow but steady effort to undermine the social fabric that makes them possible—by habituating us to cruelty, by treating facts as fictions, and by suspending the idea that we each, regardless of our national affiliation, are worthy of respect. Underneath the polices of the Trump administration is a test of the moral culture of Americans—to see what they can stand and what they will endure. When he refuses to disclose his taxes, he tests our desire for transparency. When he dismisses the media, he tests our commitment to truth. When he abets the gutting of institutions like the EPA, he tests our reliance on research and facts. Taken together his bet is a direct challenge to Dewey. How closely are the American people paying attention to the actual processes threatening our institutions rather than all the bread and circuses? How can we be so sure Trump’s transgressions will amount to a momentary blip along the arc of America’s future? Checks and balances do not have an agency of their own. In relying on the inertia of institutions, we forget that a democracy is only as strong as the men and women who inhabit it.

Democracy cannot exist without a critically informed and engaged public. Educators, artists, journalists and other cultural workers have a crucial responsibility to defend public and higher education as a democratic public good, rather than defining such institutions through market-driven values and modes of accountability defined by the financial and corporate elite. Nevertheless, raising public consciousness, especially among students, is not enough. Students need to be inspired and energized to address important social issues, learn to narrate their private troubles as public issues, and to engage in forms of resistance that are both local and collective, while connecting such struggles to more global issues.

Democracy begins to fail and political life becomes impoverished in the absence of those vital public spheres of public and higher education, in which civic values, public scholarship and social engagement allow for a more imaginative grasp of a future that takes seriously the demands of justice, equity and civic courage. Democracy should be a way of thinking about education, one that thrives on connecting equity to merit, learning to ethics and agency to the imperatives of social responsibility and the public good.

Given the current crisis of politics, agency, history and memory, educators need a new political and pedagogical language for addressing the changing contexts and issues facing a world in which capital draws upon an unprecedented convergence of resources—financial, cultural, political, economic, scientific, military and technological—to exercise powerful and diverse forms of control. If, as educators, we are to take seriously the role of nurturing in our students a robust civic imagination and social imagination, we need to develop not only a pedagogical discourse of critique and transformation, and but also a comprehensive sense of politics that draws from history while embracing a newfound sense of social and political responsibility. Against the rootlessness and atomization produced by neoliberal fascism, we need a language that finds its meaning not through the market-driven dictates of privatization, the propriety of a sterile individualism and an ethos of war and eviscerating competiveness, but in relation to others, a larger sense of community and a radical revival of the social contract. Another challenge faced by such a language is the need to create political formations capable of understanding the current plague of apocalyptic populism and fascist politics as a single, integrated system whose shared roots extend from class and racial injustices under financial capitalism to ecological problems and the increasing expansion of the carceral state and the military-industrial-academic complex.

What history reminds us is that fascism is never entirely rooted in the past, and that the ghosts of the past can reappear in different forms. As author William Faulkner once observed, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Fascism in its American appearance offers a narrative of hate and bigotry as an answer to the systemic misery and suffering produced by capitalism’s machinery of death and its toxic embrace of racial and social cleansing. The ghosts of a dark past have been once again set free, like a plague on American society. The ghosts of fascism should terrify us, but most importantly, they should educate us and imbue us with a spirit of civic justice and collective action in the fight for a substantive democratic social order. We live in dangerous times, and there is an urgent need for more individuals, institutions and social movements to come together to resist the current regimes of tyranny, see that alternative futures are possible, and understand that by acting on these beliefs through collective resistance, radical change will happen. Frederick Douglass spoke eloquently to the necessity for dramatic action and collective struggle, which both burdens hope and inspires it:

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. … It is not the light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

Such a struggle will not be easy and will not come through momentary demonstrations, or through the elections. What is needed is a massive, unified movement that takes as its major weapon the general strike, using it to shut down the fascist state in all of its registers. Only then can power be used to rethink and restructure American society through forms of collective power, in which democracy and its radical ideals of liberty, freedom and equality can breathe once again.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.