Elton John Soars as Pop Phoenix in ‘Rocketman’

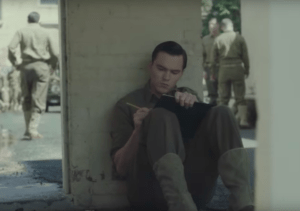

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is a tough act to follow, but “Rocketman” may just become the next nostalgic musical sensation to hit theaters. Taron Egerton suits up in sequins as Elton John in the musical biopic "Rocketman." (David Appleby / Paramount Pictures)

Taron Egerton suits up in sequins as Elton John in the musical biopic "Rocketman." (David Appleby / Paramount Pictures)

“Rocketman,” the imaginative and entertaining jukebox musical about Reg Dwight before and after he becomes Elton John, opens with Himself clomping down a corridor wearing platform heels and trailing a flurry of marabou and sequins. His horned headdress and angel wings suggest he is both devil and angel. Yet the horns and tangerine unitard also suggest that he is one of Maurice Sendak’s amiable monsters disguised as a Vegas showgirl. This is also a reasonably accurate description of John’s personality and fashion sense.

At first boisterously and then buoyantly incarnated by Welsh actor Taron Egerton, the pop star looks dressed for a gig at Madison Square Garden. But his actual destination is a 12-step meeting in which he will narrate his meteoric rise, pyrotechnic fall and glittering rebirth.

In group therapy he confesses not only to alcohol addiction, but also to compulsive cocaine use. The list doesn’t stop there: He’s additionally a sexaholic, shopaholic, bulimic, pothead and prescription drug abuser with anger-management problems. (As the film was produced by John and his husband, David Furnish, it is an authorized account.)

In Fletcher Dexter’s affectionate, and frequently affecting, movie, the feathered one recalls the musical facility that made him and the parental neglect that made him unsure of himself as a man and a sexual being. Some have photographic memories; John has a phonographic memory; i.e., he has the ability to remember and replicate music he hears, from Franz Schubert to Jerry Lee Lewis. In therapy, the adult John reconnects with his youthful selves (marvelously incarnated by the pre-teen Matthew Illesley and teenage Kit Connor), remembering who he was before someone gave him the bad advice to kill the person he was born in order to become the one he wants to be. Therapeutically, this helps Screen Elton to integrate who he once was with who he now is. It’s also a convenient way to fill in biographical blanks for the audience.

Dexter, who replaced Bryan Singer as director of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” relies on a script from Lee Hall (“Billy Elliott”) as a means of framing this musical, punctuated by nearly two dozen songs from the Elton John/Bernie Taupin songbook. With two exceptions, the music and musical numbers neither lyrically nor literally reflect where Elton John was, biographically speaking, at a chronological moment. Rather, impressionistically they evoke a certain mood or energy and propel the pop opera forward at warp speed.

Jamie Bell, the gifted actor best known for “Billy Elliott,” nicely underplays the role of lyricist Bernie Taupin, seen here as the fulcrum of a seesaw relationship. Bell and Egerton’s rapport as Taupin and John, longtime partners who sustain a half-century-long platonic bromance, is an unexpected surprise and deeply touching.

The sequence in which John first reads Taupin’s lyrics to “Your Song” and immediately sets them to music suggests that it reflects the joyous intimacy between a gay man and a straight man. “Your Song” becomes Their Song … and ultimately, Everyone’s Love Song.

Equally great as this sequence, is that of John’s 1970 U.S. debut at the Troubadour in Los Angeles. (Here, he gets slightly better advice, that the secret to rock immortality is to put on a great show and don’t mess with drugs.) Clad in a black T-shirt festooned with stars and white overalls embroidered with sequins, he performs a bouncy rendition of “Crocodile Rock” (a song not written until 1973, for sticklers for historical accuracy).

Dexter imagines that when John, standing before the piano, sings “Crocodile Rockin’ is something shockin’ when your feet just can’t stand still,” his weightless body floats horizontally above the keys and stops time. And that his mesmerized audience levitates a few feet above the club floorboards. The scene perfectly captures the gravity-defying feeling of a great rock performance.

But not every sequence of “Rocketman” is so thrilling. There is the obligatory second act replete with excess, involving blackouts and attempted suicide as John’s first male lover (and manager) John Reid (a snakily seductive Richard Madden) preys on the insecurities of his client and live-in partner. And there are John’s respectively prickly and painful encounters with his divorced mother (Bryce Dallas Howard) and father (Steven Mackintosh), who act like the bad guys in Victorian melodrama.

Still, by the finale (ending some time before its frontman becomes Sir Elton), the movie feels of a piece. Like the Elton John it presents, it’s about forgiveness. Love is love is love. Watching so many plume-festooned costumes take wing, you’re inclined to believe that hope really is the thing with feathers.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.