The Judiciary Won’t Save American Democracy

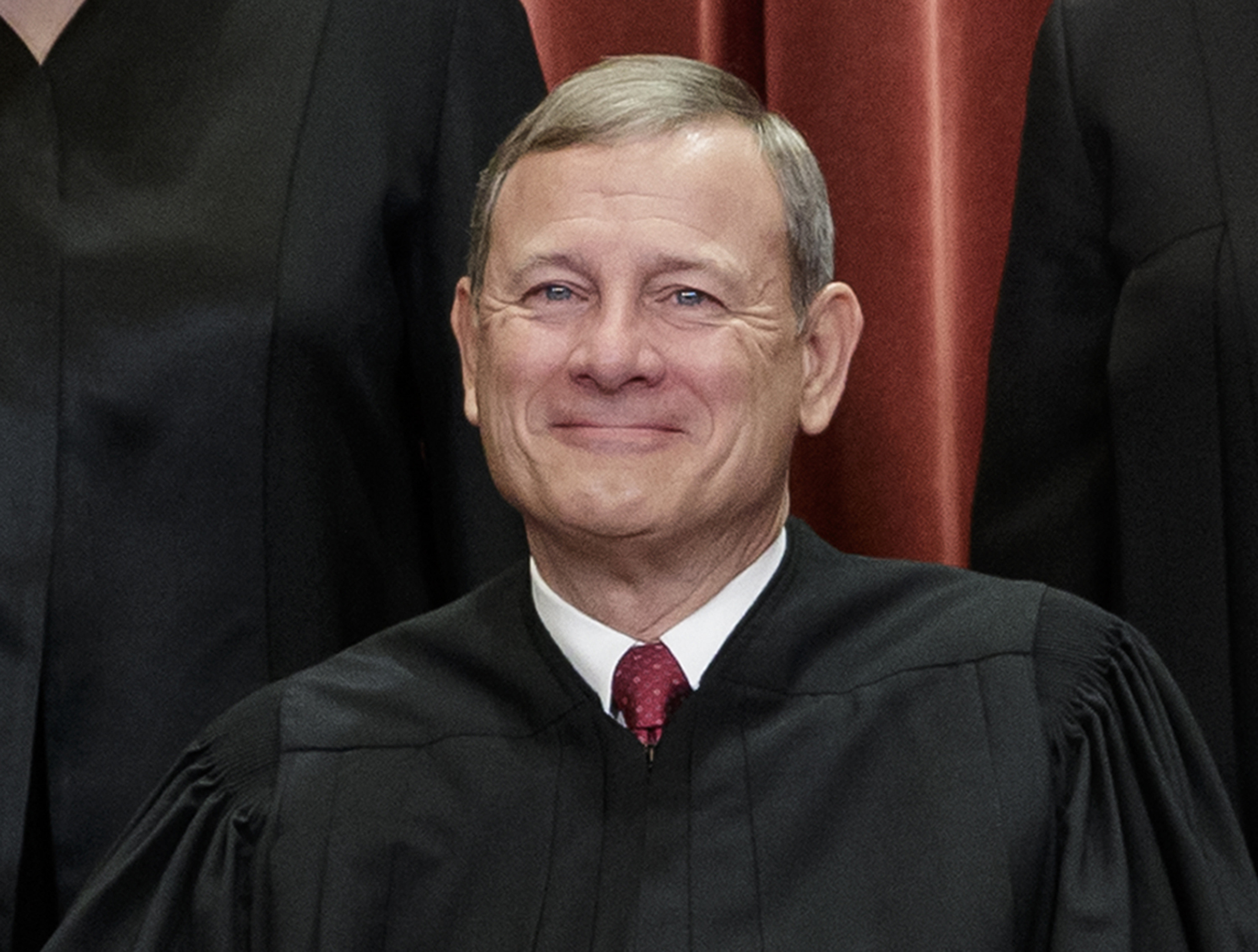

Donald Trump has declared a fake national emergency to secure funding for his border wall, and our courts are unlikely to stop him. Chief Justice of the United States John G. Roberts. (J. Scott Applewhite / AP)

Chief Justice of the United States John G. Roberts. (J. Scott Applewhite / AP)

Update: On February 25, the House voted to pass the joint resolution terminating the border emergency declaration by a vote of 245-182. Thirteen Republicans voted with the majority. The measure now moves to the Senate.

Now that President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to pave the way for construction of his long-promised wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, the question is whether anyone or anything can stop him.

On Tuesday, the House is expected to pass a joint resolution terminating the emergency. The resolution will then head to the Senate, which should vote on it by mid-March. In addition, at least six high-profile federal lawsuits have been filed to contest the emergency decree.

Unfortunately for anyone concerned with preserving the last vestiges of American democracy, the emergency declaration is likely to stand. Before explaining why, it’s helpful to recall how we got here.

Trump proclaimed the emergency on Feb. 15 in a rambling, self-centered, stream-of-consciousness Rose Garden speech more suited to a psychiatric session than a presidential event. Careening from such far-flung topics as his personal relationship with China’s Xi Jinping and his admiration of China’s death penalty for drug offenders to the second summit with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, the status of Brexit and the latest military developments in Syria, Trump finally got to the point and explained he was dissatisfied with the $1.375 billion Congress had appropriated for 55 miles of new border barriers in the Rio Grande Valley to avert another government shutdown.

Declaring a national emergency, he continued, would free up nearly $7 billion in additional funding to build “a lot of wall.” A “White House Fact Sheet” distributed along with the emergency declaration clarified where the added money would come from:

- $601 million from the Treasury Department’s forfeiture fund,

- $2.5 billion from Department of Defense funds earmarked for support of counterdrug activities, and

- $3.6 billion from Department of Defense military construction projects.

In a question-and-answer session with reporters following his speech, however, Trump admitted there was, in fact, no actual emergency at the border. “I could do the wall over a longer period of time,” he said, referring to the alternative of continuing to negotiate with Congress. “I didn’t need to do this. But I’d rather do it much faster.”

In truth, in terms of illegal immigration and drug smuggling, there is no crisis along the U.S.-Mexico frontier. Undocumented immigration has dropped to the lowest levels in decades, and the vast majority of drug contraband—heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and fentanyl—crosses into the U.S. at ports of entry rather than through unfenced areas of the border.

Both undocumented immigration and drug trafficking are chronic conditions that should be addressed through regular legislative channels. There are, moreover, already 654 miles of walls, barriers and fences along the border, and that number that will soon rise to 709 with Congress’ recent appropriation.

The problem, legally, is that the National Emergencies Act (NEA) of 1976, the law that enabled Trump to make his declaration, provides an easy pathway to abuse of power. Enacted in the aftermath of Watergate to place congressional checks on the emergency authority of the president, the act has proved to be a dismal failure in practice.

First and foremost, among the NEA’s defects is that the act contains no definition of an emergency. As I outlined in a previous column, the NEA gives the president complete discretion to decide when and if an emergency exists.

Once a declaration is issued, the president can access emergency powers contained in 123 federal laws, some of which permit the reallocation of funds previously appropriated by Congress to address the emergency. Trump’s declaration cites a statute (Title 10, Section 2808 of the United States Code) that allows the president to direct the Secretary of Defense to undertake military construction projects in times of war or national emergency.

In 1990, during the first Gulf War, George H.W. Bush invoked Section 2808 in an emergency declaration. And in 2001, George W. Bush invoked the statute in response to the 9/11 attacks. Before Trump, however, no president had declared a national emergency to reallocate funds that Congress explicitly had declined to appropriate.

Prior to Trump’s Feb. 15 proclamation, a total of 59 national emergencies had been declared under the NEA. Thirty-one remain in effect, including the first emergency declared under the NEA, issued by President Carter in 1979, which froze Iranian government assets in the U.S.

As originally written, the NEA gave Congress the power to override an emergency declaration by a simple majority of each chamber. In 1983, however, Supreme Court held in an unrelated case (INS v. Chada) that such “legislative vetoes” are unconstitutional.

This means that a two-thirds majority of both the House and Senate would have to vote in favor of the pending joint resolution to terminate the border emergency to overcome an anticipated Trump veto of the measure. Given the GOP’s shameless and complete capitulation to the president on virtually all matters of national policy, that simply isn’t going to happen.

To ensure that the GOP-controlled Senate remains loyal, Trump sent out an urgent tweet Monday morning, saying: “I hope our great Republican Senators don’t get led down the path of weak and ineffective Border Security. Be strong and smart, don’t fall into the Democrats ‘trap’ of Open Borders and Crime!”

There is slightly more reason for optimism on the litigation front. To date, major lawsuits have been filed to overturn the emergency declaration by 16 states led by California; the County of El Paso, Texas; the ACLU; the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Public Citizen Litigation Group. In addition, the nonprofit watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) has filed a Freedom of Information Act complaint to compel the Trump administration to release the records it has relied on to support its claims of a border crisis.

Although filed in different federal courts stretching from San Francisco to El Paso and Washington, D.C., the lawsuits contend the situation at the border is a fake crisis, citing Trump’s Rose Garden admission that he did not need to proclaim an emergency. The lawsuits also contend that only Congress holds the “power of the purse” to appropriate federal funds under Article I of the Constitution, and that building a border wall cannot be deemed a military construction project under Section 2808 or any other provision of federal law.

Such arguments, if presented persuasively, may convince some lower-court federal judges that a presidential coup d’état is underway, but they may nonetheless fall short before the Supreme Court if the legal challenges advance that far.

Last year, in Trump v. Hawaii, in a hotly contested 5-4 decision, the court approved the third version of the president’s Muslim travel ban. In reaching its conclusion, the court reasoned that while Trump’s anti-Muslim public statements could be considered in determining if the ban discriminated on the basis of religion, the text of the ban was more important. The text, the court held, was neutral on its face, and the ban thus fell well within the president’s discretion.

The majority opinion in the travel ban case was written by Chief Justice John Roberts. Now widely viewed as the court’s new swing justice, Roberts will have to distinguish the travel ban from the border emergency if Trump is to be thwarted this time around.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.