The Trouble With Nondisclosure Agreements

Saving time and money doesn't always serve the cause of justice. Stephanie Clifford, also known as Stormy Daniels, and her attorney, Michael Avenatti. (Michael Nigro)

Stephanie Clifford, also known as Stormy Daniels, and her attorney, Michael Avenatti. (Michael Nigro)

In a famous American folk tale, a naive young man suffers from a whopping case of buyer’s remorse after selling his soul to the devil. He is saved by a stirring speech from the great lawyer and orator Daniel Webster, which sways a stacked jury of spirits and frees him from Beelzebub’s clutches.

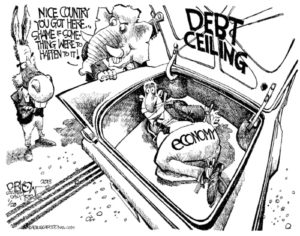

These days, a tsunami of lawsuits resulting from deals made with a host of demons has clogged our courts and prompted many judges to push for settlement agreements just to keep the system afloat. The public interest is best served, they reason, by getting civil disputes resolved without the enormous time and expense of lengthy trials.

But saving time and money doesn’t always serve the cause of justice. In this rush to judgment, the courts end up rewarding defendants—often corporations accused of everything from product safety violations to environmental disasters—while punishing many plaintiffs who have suffered extensive damages from those crimes, because these settlements are often structured in ways that enable the wrongdoer to keep doing wrong. With the system thus tilted to the rich and powerful, it’s doubtful that even Daniel Webster could rescue victims from the misdeeds of modern-day devils.

The problem isn’t the negotiated settlements. It’s the onerous caveats attached to them known as nondisclosure agreements (NDAs), or more commonly, gag orders. These orders prevent those who accept money in a settlement from disclosing anything negative about the defendants.

If this sounds familiar to you, that means you’re up on the latest Donald J. Trump scandals. To wit: Stormy Daniels, an adult film star, allegedly had an affair with Trump in 2006. When she started shopping the story around to magazines prior to the 2016 election, Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, paid her $130,000 to clam up about it. Daniels now wants to break the nondisclosure agreement, which includes hefty fines for violations. Trump denies the affair and any knowledge of the payment. He insists he didn’t reimburse his lawyer. If anything, the Trump-Daniels brouhaha has significance if, for instance, the payment to Daniels could be construed as an illegal, campaign-related expense. Many argue that the body politic has a right to know about the sins of the president, in order to judge his fitness for office. To me, those are minor considerations in evaluating the long-term impact of nondisclosure agreements.

And to be clear, I’m not advocating the elimination of gag orders. In some cases, they are appropriate and necessary. Legitimate trade secrets must be protected, and embarrassing information can be sealed if there are no public concerns. I even favor sealing divorce settlements, absent any showing of good cause why the information should be made public. Most divorces are private matters. Even heated disputes rarely involve things the public needs to know, and their disclosure could have a negative impact on the couple’s children.

But in many cases, nondisclosure agreements inhibit the public’s First Amendment right to speak out on matters of public concern and the right of civil litigants to gain access to information from prior settlements that are directly related to their cases. In addition, the payments of huge damages in these settlements would warn the public and deter the offender from repeating the crime.

But if no one can reveal details of the settlement publicly, how can such beneficial social goals be accomplished? The ability to conceal these details from the public and potential future litigants has prompted many corporations, cults and self-help groups to seek out possible aggrieved parties—sometimes even if they haven’t yet filed a lawsuit—and offer them princely sums of money in exchange for their signatures on nondisclosure agreements. If the potential litigants had come to the offender and demanded payment for their silence, it would be considered blackmail. But ironically, the courts have blessed wrongdoers that seek out and pay potential plaintiffs in order to prevent them from ever revealing details of a settlement, speaking to the media or otherwise aiding potential litigants. It also keeps critical documents and other evidence away from the prying eyes of other litigants.

Often, the organization seeking to conceal its wrongdoing settles with the plaintiffs that have the most information or the best lawyers, thus making it more difficult for other litigants to pursue legal redress. These agreements don’t prevent potential witnesses from being deposed or testifying—that would be obstruction of justice. Advocates of settlement agreements argue that this limits the damage created by these agreements. But it does make testimony more difficult to obtain. To properly prepare for a trial, lawyers must review critical documents and interview witnesses privately. NDAs restrict their ability to do either.

Depositions, for example, cost thousands of dollars each and are made more difficult with the defendants’ legal eagles present and badgering witnesses, threatening to sue if they don’t remain silent. Of course, you can skip all that, but what lawyer would risk interrogating a witness whose likely testimony is unknown? Without access to the details of previous settlements, the cost and risks of preparing these cases skyrockets for plaintiffs whose resources are usually dwarfed by those of their adversaries.

Many courts aggressively push for out-of-court settlements in order to relieve the crushing backlog of cases. It’s an understandable goal. But by doing so, they are in effect saying that clearing cases is more important than giving plaintiffs a fair shot at justice, informing the public about dangerous situations or deterring criminal organizations from continuing to commit crimes. The courts are actively participating in cover-ups of criminal/immoral activity and hindering the pursuit of justice.

I also believe that fears of increasing caseloads are unwarranted. Few defendants on the verge of settlement will toss that aside just because the courts won’t allow them to add a gag order. And if violators’ feet are held to the proverbial fire, it should result in fewer lawsuits long-term. Think of the money that would save. A more restricted use of gag orders would serve the public better in the long-run.

Consider the case of a self-help guru and former protege of Est’s Werner Erhard who reached a settlement with a number of women he pressured to have sex with him. The women signed NDAs that prevented them from warning other women in the group. Those who weren’t party to the settlement couldn’t access documents filed with the court. How can we, as a society, tolerate a legal system that allows a sexual predator to continue hurting women by covering up his improper actions? What in the name of Harvey Weinstein is going on here?

In another case, a psychologist seduced many of his female patients, transgressions that resulted in the loss of his license. He settled a lawsuit with the women but obtained a gag order that prevented anyone from disclosing the amount of the settlement. Years later, as the pastor and principal of a private school, he was once again charged with abuse—with adults and children. Had the details of the first settlement been made public, might that have prevented the later abuse?

Ironically, even the courts have used gag orders to cover up bad behavior. On April 10, California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye urged the Judicial Council to ban secret settlement agreements involving sexual harassment by judges. Apparently, the council doled out more than $600,000 of taxpayer money recently to investigate and settle three such complaints—and naturally, the settlements included nondisclosure agreements. “The public has a right to know how the judicial branch spends taxpayer funds,” the chief justice said. Alas, the chief justice is still falling short of justice, though new rules could change that.

Here, secrecy isn’t the only issue. Taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay damages for the intentional misdeeds of public officials. Hear that, Congress? More importantly, it is time to stop secret settlements when they relate to public safety or other public concerns. There has been some progress made in this direction. Some courts use a weighing tool to determine whether public interest outweighs the right to privacy. A Florida statute prohibits the concealment of public hazards in settlement agreements. California does not permit nonfinancial confidentiality of motor vehicle problems in its lemon law settlements. A bill is pending that would allow greater disclosure of the details of settlements in sex crime cases.

We need more. You can’t buy silence or suppress documents when doing so would harm the public interest. No confidentiality agreement should be permitted that would make the devil smile.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.