‘La Raza’ Again Empowers L.A.’s Chicano Community (Photos and Audio)

A new exhibit at the Autry Museum showcases how the newspaper-turned-magazine shaped history and resonates with today's national issues. La Familia at the Mexican Independence Day parade in East Los Angeles in September 1970. (La Raza staff, courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

La Familia at the Mexican Independence Day parade in East Los Angeles in September 1970. (La Raza staff, courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

Photo Essay

‘La Raza’ Again Empowers L.A.’s Chicano Community

Photo Essay

‘La Raza’ Again Empowers L.A.’s Chicano Community

Watch and listen to Liesl Bradner’s accompanying of the “La Raza” exhibit.

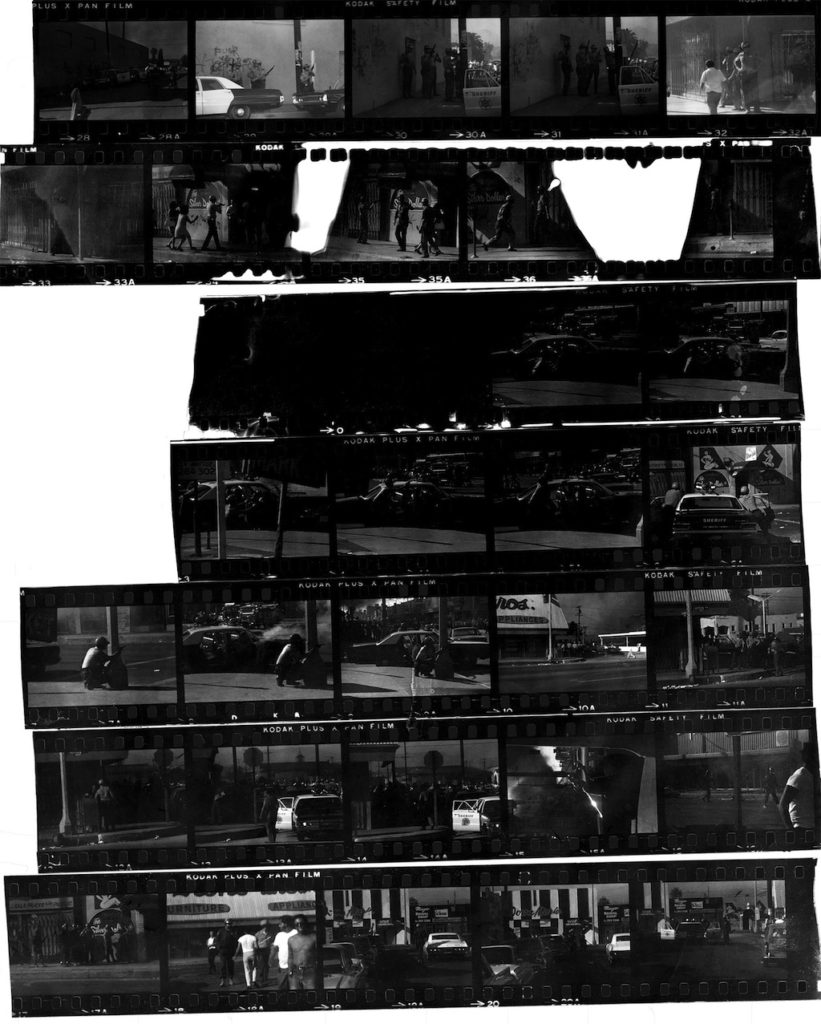

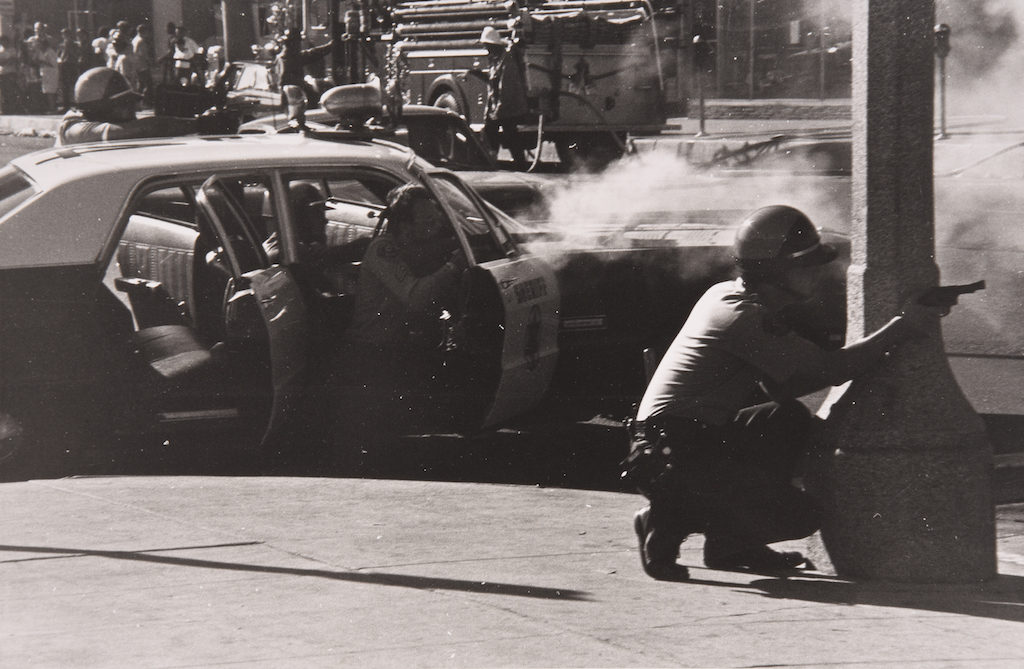

On Aug. 29, 1970, La Raza, a little-known bilingual Los Angeles newspaper-turned-magazine became an influential part of the Chicano rights movement. While covering a massive anti-Vietnam War rally in East Los Angeles, Raul Ruiz, the La Raza editor in chief, captured the moment a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy fired a Flite-Rite tear gas missile into the Silver Dollar Café. Ruben Salazar, a former Los Angeles Times columnist and a leading Latino voice of the 20th century, had just entered the crowded bar to quench his thirst after covering the protest. Minutes later, he was dead.

The black-and-white photo taken from the sidewalk that hot August day is considered one of the most well-known and contentious images representing the plight of the Chicano movement (El Movimiento) during the civil rights era.

“The Killing of Ruben Salazar” wall—a series of pictures and video footage from that fateful day—is now part of an exhibit at the Autry Museum of the American West called “La Raza.” The exhibit, which opened Sept. 16 and has been extended through January 2019, features 270 rarely seen images by La Raza photographers.

La Raza was in operation for only 10 years, from 1967 to 1977. But during its short-lived existence, the publication churned out nearly 25,000 images of the social justice struggle and became a voice for the Chicano movement. Now, La Raza is getting its just share of the spotlight as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, which explores Latino art and identity in Los Angeles.

The exhibit has been in the works for the past six years, and its unforeseen timing resonates with current issues confronting Mexican-Americans. “It was serendipitous,” said Amy Scott, the Autry’s chief curator. “We couldn’t have anticipated the present national discourse. The parallels between what was going on then and now are uncanny.”

While the millennial generation of today marches in protests for women’s rights, DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) and United States-Mexico relations, their civil rights era compatriots staged massive school walkouts protesting an educational curriculum that prepared Chicanos for manual or domestic labor instead of college.

In 1971, La Marcha de la Reconquista was a 1,000-mile, three-month-long march from Calexico, Calif., near the border of Mexico in Imperial County, to Sacramento, Calif., for farmworkers’ rights, better education, prison reform and accountability for police actions. The 30,000-strong Chicano Moratorium of Aug. 29, 1970, in East Los Angeles called for an end to the Vietnam War.

“Our past is relevant to issues we’re confronting today such as immigration, education, migrant farm workers, equal pay and DACA,” said former La Raza photographer and exhibition co-curator Luis C. Garza.

Scott noted, “Prior to La Raza, Mexican and Western photography were federally run projects depicting Indian tribes, Dust Bowl era migrants and Mexican housing projects. It was a way of marginalizing ethnic groups in the West.”

La Raza took that model and turned it on its head. “Photographers took cameras into their own hands as a means of empowerment, seizing control of their own community image and means of self-representation,” Scott said.

It was also a way to counter mainstream media narratives and representation of Chicanos as criminals and gangsters, similar to the rhetoric spewed in the 2016 presidential election.

Many photos reveal lesser-known community actions, including a young girl protesting unfair labor practices at a Chevrolet car dealership and a family attending the Mexican Independence Day parade. Another photo shows two Brown Beret (a pro-Chicano organization modeled on the Black Panther Party) high school students being handcuffed during the Belmont High School walkouts. There’s a picture of a recently wed couple marching with a crowd to protest the excessive number of Chicanos who were drafted, injured and killed in the Vietnam War.

The standout photograph of the show is that of a 5-year-old girl with braided pigtails clutching a handful of La Raza newspapers under her arm. Her mouth wide open, she is shouting like a turn-of-the-century newsy, pushing copies of the paper during the Poor People’s Campaign Rally in Washington, D.C., which ran from May to July 1968.

Most posters were simple statements with homemade slogans such as: “USA Immigration Policy Is Nazism,” “There is Money for War–None for Workers” and “To Protect and to Serve to Shoot in the Back.”

“We were constantly in harm’s way. We risked bodily harm to take photographs,” said Garza, who recalled frequent raids and being forced to throw cameras and film canisters out of windows as police knocked on the front door. “We were activists first and foremost. La Raza was our organizing tool.” Murals, poetry and graphic arts were all used to reach out to the community at large.

“It wasn’t just about reporting but about the community and giving a voice to a system that systematically excluded us,” Garza said. “Look at California today. We’ve made very clear strides and successes along with failures. Our movement from that day on collectively made a difference in California politics.”

Editor’s note: To read more about the Los Angeles Chicano community’s reaction to the controversial death of journalist Ruben Salazar, read Hunter S. Thompson’s “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” which was published in Rolling Stone in April 1971.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.