Survivors in Ukraine

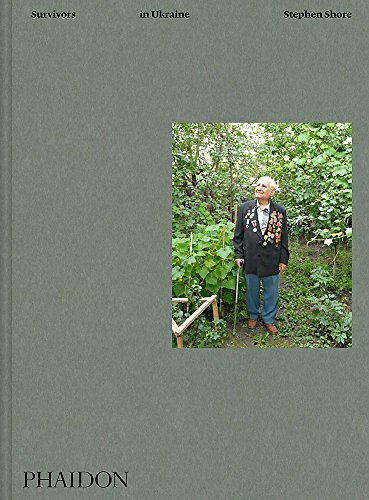

Stephen Shore's book is a potent photo-documentation of Holocaust survivors in their twilight years and a testament to how one lives within a community that shares collective traumatic memories. From the cover of Stephen Shore's "Survivors in Ukraine." (Phaidon)

From the cover of Stephen Shore's "Survivors in Ukraine." (Phaidon)

“Survivors in Ukraine” A book by Stephen Shore

In 2012, photographer Stephen Shore, whose Ukrainian grandfather immigrated to America in the late 19th century, embarked on a two-year journey through western Ukraine, visiting and photographing 22 Holocaust survivors, their humble belongings, and surrounding environment. They were the lucky ones, able to live out their lives for 70 years after the fall of the Third Reich. These images are gathered in his latest book, “Survivors in Ukraine.”

“Survivors in Ukraine” is an unconventional but potent documentation of Holocaust survivors in their twilight years. Their lives are reflected in images of their surroundings, objects and oral histories. It is a testament to how one survives and carries on within a community that shares collective and traumatic memories bubbling just beneath the surface.

At the onset of World War II, there were 2.7 million Jews living in Ukraine, the third-largest Jewish population in Europe. By the end of the war, 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews had been killed by the Nazis. Today approximately 63,000 remain.

The individuals featured in Shore’s book are members of the Survivor Mitzvah Project, which provides emergency aid to elderly survivors of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe.

Shore is best known for his pioneering use of color photography and attention to ordinary objects. Images of everyday Americana — signage, motels and roadside diners found along the back roads and highways — are chronicled in two of his most popular books, “Uncommon Places” and “American Surfaces.” Lately, the 68-year-old New Yorker and director of the photography program at Bard College has been focusing on more introspective, personal projects, including an intimate look at Israel and the West Bank with “Stephen Shore: From Galilee to the Negev.” Shore was once described as “a poet of the mundane,” which explains photos of filthy floors, bowls filled with yellowish-brown water, and ancient cracked family pictures.

Ukraine was unique in its suffering as Jews were not immediately sent to concentration or labor camps until 1944. As Nazis marched through the country on their way to conquer Russia in 1941, Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo and the Waffen-SS, ordered death squads, or Einsatzgruppen, to round up the Jews and execute them on the spot in ditches and pits near their homes.

The Massacre of Babi Yar was one of the most infamous mass atrocities committed against the Ukrainian people. In September 1941, collaborators and local police rounded up and slaughtered 34,000 Jews, Russian prisoners and other undesirables, filling the ravine of Babi Yar in Kiev with their corpses. Survivors hid in attics and barns, or escaped through the woods on foot to Kazakhstan, more than 2,000 miles away, where they were put to work with Russian Jews in factories and collective farms.

Tzal Nusymovych, 93, who graces the cover of the book, was one of the thousands of young men who joined the Russian Army rather than turn Nazi sympathizer. Head held high, the white-haired war veteran proudly wears his uniform jacket adorned with a multitude of medals, while leaning on a cane and smiling, looking up to the heavens. He poses in the garden of his home, the same one his family fled from in 1941.

He was just 19 when he fought for 41 weeks during the bloody Battle of Stalingrad. In the aftermath of a particularly vicious clash, Nusymovych recalled offering water to a dying German soldier. When his officer gave him hell for helping the enemy, he replied: “When he was a soldier, he was my enemy. When he’s dying, he’s a man like me.”

Many of Shore’s survivors rarely spoke about the past, preferring to discuss their health issues and medicine. They carefully displayed their plethora of pills, and shelves stuffed with tchotchkes from another era. Busts of Lenin and Stalin are visible in the “best rooms” of nearly every home, a reminder that it was the Soviets who saved them.

Shore’s 175 images reveal the interiors and exteriors of dilapidated structures, overgrown weeds, the inside of a scantly stocked refrigerator, outdated appliances frozen in time and pictures of food — but hardly the mouthwatering Instagram fodder we’re used to seeing. Yet lace curtains were hung with care.

Shore contrasts bleak images with his signature landscapes. Young people frolicking in a river, or resting in lush fields overflowing with foliage and grazing farm animals, are juxtaposed with photos of impoverished lives yet filled with gratitude.The book may feel dreary if you’re expecting a standard coffee table tome. Best viewed like an old family photo album — quiet, random, introspective and, yes, somber — it’s also powerful in its tale of resilience in the face of unbelievable barbarity and an example of how one moves on when the past is always simmering just beneath the surface.

Accompanying the visual narrative is a poignant six-page essay by The New Yorker’s European correspondent, Jane Kramer, which focuses on the harrowing journey of Anna Gribun Perlova. The 23-year-old schoolteacher fled Kherson along with 11 members of her family in August 1941. Along the way to Kazakhstan they encountered bouts of starvation, kindness, and tragedy when shrapnel from a German bomb killed Anna’s 70-year-old father instantly. When the fighting in Stalingrad began, they were forced to flee across the Volga River, eventually making the long trek to Kazakhstan where she worked in a factory. Described as small, thin and frail “like a bird,” Anna survived longer than her much stronger sisters.

“Somehow I am alive and now they’re not, so maybe I was the strongest of all” –that, she said, was the most important thing she learned. “To stay alive, to survive, to unite my family and see my two year old son, who remembers the day his grandfather was hit by a bomb, now in his seventies … to celebrate his 45th wedding anniversary. It was important for me to live to see that.”

Notes Kramer: “Ukrainians have suffered far more predation than they have enjoyed peace.”

Anna died a year after her interview, at the age of 95, before the book was published.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.