A Progressive American in London: My Thoughts on Brexit and the Revolt Against Jeremy Corbyn

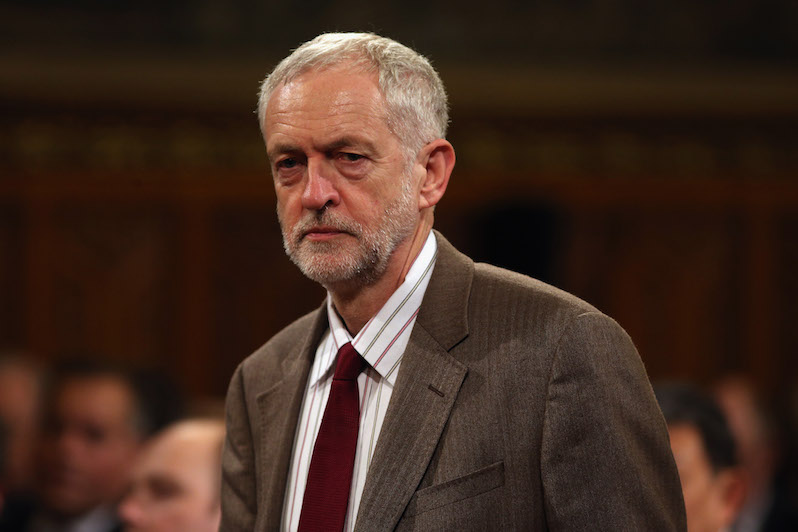

After voting to leave the European Union, the U.K. needs serious discussions on a progressive way forward. For that, it needs Corbyn at the helm of the Labour Party. If Labour politicians want to point a finger at someone in their party, it’s wrongheaded to use Jeremy Corbyn. (Dan Kitwood / Pool photo via AP)

1

2

If Labour politicians want to point a finger at someone in their party, it’s wrongheaded to use Jeremy Corbyn. (Dan Kitwood / Pool photo via AP)

1

2

LONDON — Jeremy Corbyn took the stage Monday night to thank a diverse crowd of several thousand followers gathered in Westminster to show Labour Party members of Parliament that their leader still had widespread public support. Undeterred by the fact that two-thirds of his shadow Cabinet had resigned in the previous 24 hours, Corbyn reminded the public that the political party he leads has its roots in activism, trade union movements, women’s rights and socialism—and he wasn’t going to forget that as so many in his party seem to have.

Like many at the rally, I asked myself how the Labour leader had become the headline in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, a public vote on whether the United Kingdom should stay in the European Union or leave it. (As the world knows by now, the Leaves had it.) To me it seemed that the decision had given progressives like Corbyn the opportunity to push a leftist agenda as the Conservative government crumbled. It’s been clear since he was elected in a landslide less than a year ago that many centrist and right-wing Labour politicians were unhappy with the socialist leading the party. And yet, I had assumed now would be the time for Labour to unite behind him and deal with the “catastrophe” the Tories had set in motion with the EU referendum, especially as the threat from the xenophobic far right gained traction. But just as I had been wrong in my prediction of the Brexit vote results (as had been the polls, politicians and pretty much everyone), I was wrong about Labour.

On Friday, London woke up in shock to the news that 52 percent of British voters had chosen to leave the EU. I had spent the previous day on the streets of the capital, talking to people, both those who could and those who couldn’t vote, about the referendum. I realized early on that the polls were right: The country was divided on the topic, even in London. My first, rather unfortunate encounter was with a man at my local Wetherspoons pub who spouted racist quips about Muslims and refugee children. But he was the only one out of dozens I spoke to that day who expressed so much hate. Others, such as my Northern English flatmate, explained their “Leave” votes in terms of EU regulations killing small businesses in the U.K. Even so, there was a consistent thread in even the less-heated conversations—immigration.

“The U.K. can’t control its borders,” one woman told me as her friend, who couldn’t vote because of her immigration status, stood by.

When my British partner, Richard, and I braved floods and train cancellations to reach East Sussex so he could vote in the village where he grew up, we were greeted by his mother and grandmother, who’d voted by mail days before.

Over tea and cake, his grandmother explained her Leave vote: “It’s natural that us older folks want to leave the world how we came into it.” She, like 59 percent of her age group, did not seem to mind that the world they wanted to leave for their descendants was not the one the young people wanted.

Richard has spent almost as much of his life outside of England as he has here—he’s lived, studied and worked in Spain, Norway, Portugal and Scotland. I too have spent a lot of time in the EU countries—in Spain, Portugal and Scotland with him, as well as in the Irish Republic and England for various stints of study and work. To both of us, the choice by so many Britons on Thursday truly came as a shock, even after all the conversations we’d had with people of various ages who had vowed to vote Leave. Like Greece’s Yanis Varoufakis, we still believed in a progressive vision of what the European Union could someday become — perhaps in the hands of our generation, a majority of which voted Stay.

As a second-generation American who has spent plenty of time filling out EU visa forms and standing in seemingly endless immigration lines, I have always envied my European friends their star-covered passports that allowed them to live and work in so many countries. Rich and I will have to cut through a lot of red tape (including providing proof of income and evidence that we’ve maintained a meaningful relationship for more than two years) so that I can more permanently live with him in the U.K., where he now works. But our European friends have no such hassles. Even more envy-provoking were their E111 health cards, granting them free access to all public health systems in the EU. Many of our peers, Richard included, had also taken part in the Erasmus Programme, a study-abroad project that encourages university students throughout the EU to immerse themselves in the many languages, cultures and ideas that the union represented.

The European Union, however, goes beyond passports, healthcare, working rights and study-abroad programs, and I have witnessed firsthand the pain a disconnected political elite in Brussels has inflicted on countries such as Spain and Portugal through brutal austerity measures. I watched in horror as Germany wielded its considerable power against Greece and forced the country’s vulnerable back against another economic wall. I even understood the leftist case for leaving the EU, and yet I was still more in line with the Labour Party’s John McDonnell and with Varoufakis, who “campaigned for a radical remain vote reflecting the values of our pan-European Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) … argued that its disintegration would unleash deflationary forces of the type that predictably tighten the screws of austerity everywhere and end up favouring the establishment and its xenophobic sidekicks.” Perhaps we were naïve or blind or both to hope that others could believe in the same inclusive, progressive EU we felt we could build through reform and activism. But communities in the U.K. have also suffered from austerity measures inflicted by its own Tory government that have created a sense of desperation throughout the nation. Take a look at what my Truthdig colleague Roisin Davis reported after the 2015 election that gave blue-blood Prime Minister David Cameron a fresh democratic mandate:

SUPPORT TRUTHDIG

Under the Tories, the number of food banks has already increased from 56 to 445, and, according to a University of Oxford study, the Conservatives’ cuts will force 2.1 million Britons to use food banks by 2017-18, double the current figure. Ignoring the root causes of food-bank dependency, Cameron’s party will ensure that the wealthy are protected above all else. Even though his government came to power in 2010 on a deficit-reducing platform, government spending has been reduced by only 3 percent, and the money cut from services has in fact been recycled into lavish tax breaks for the rich—a 7 billion-pound prize (almost $11 billion) for returning Cameron to Downing Street.Many Britons were unable to separate their feelings about Cameron and his Tory cronies from their resentment toward the EU, which they saw as a large, bureaucratic entity of unelected officials hampering their country’s growth and allowing an influx of immigrants they felt were taking British jobs. What’s worse is that another Eton/Oxford grad was able to use Britons’ tangible, legitimate grievances and wrap them in xenophobia to distract from the role his own party has played in the decline of the U.K.: Boris Johnson, the former Conservative mayor of London whom many call the “British Trump.” Johnson emerged several months ago as the face of the Leave campaign, a move that many, even those within his own party, viewed as opportunistic. Meanwhile, Cameron used the threat of the Brexit referendum to essentially blackmail the EU into giving the U.K. even more special treatment than it already had, as well as to settle infighting among Tories. The arrogant gamble, the second he’d taken as prime minister (the first being the Scottish independence referendum), backfired and he was forced to resign Friday morning. I had previously thought that in the event of a Leave result, Cameron’s resignation would somehow soften the blow. But what I realized on Friday was that he would probably be replaced by someone further to the right, a politician more craven and callous, one even more willing to scrap the National Health Service and lie to the U.K. public with a smile on his face. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise that despite riding around in a big red bus emblazoned with “We send the EU £350 million a week. Let’s fund our NHS instead. Vote Leave,” Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right U.K. Independence Party, and others in the Leave camp immediately backtracked. Regarding the immigration they’d promised to magically stop: Soon after the referendum results came in, Conservatives decided it was irrational for Brits to believe that free movement of labor from the EU would cease. Conservatives seem to think this is all some sort of game in which politicians can lie to the public and exploit suffering to stir up racism without consequence, but the results of their xenophobic campaigning speak for themselves. Several of my friends from Spain, Romania, Lithuania, Italy and other countries have expressed something similar to what I felt after the vote: an overwhelming sense of being unwelcome. Account after account has emerged of racist attacks against people perceived as foreigners, with shouts of “Go back home.” As The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald put it in an excellent piece titled “Brexit Is Only the Latest Proof of the Insularity and Failure of Western Establishment Institutions”:

… [D]irectly contrary to what establishment liberals love to claim in order to demonize all who reject their authority — economic suffering and xenophobia/racism are not mutually exclusive. The opposite is true: The former fuels the latter, as sustained economic misery makes people more receptive to tribalistic scapegoating. That’s precisely why plutocratic policies that deprive huge portions of the population of basic opportunity and hope are so dangerous.Vincent Bevins, a Los Angeles Times reporter, wrote what I consider one of the best analyses of the referendum results:

Both Brexit and Trumpism are the very, very, wrong answers to legitimate questions that urban elites have refused to ask for thirty years. Questions such as – Who are the losers of globalization, and how can we spread the benefits to them and ease the transition? Is it fair that the rich can capture almost all the gains of open borders and trade, or should the process be more equitable? Can we really sustainably create a media structure that only hires kids from top universities (and, moreover, those prick graduates that can basically afford to work for free for the first 5-10 years) who are totally ignorant of regular people, if not outright disdainful of them? Do we actually have democracy, or do banks just decide? Immigration is good for the vast majority, but for the very small minority who see pressure on their wages, should we help them, or do they just get ignored? Since the 1980s the elites in rich countries have overplayed their hand, taking all the gains for themselves and just covering their ears when anyone else talks, and now they are watching in horror as voters revolt. It seems in both cases (Trumpism and Brexit), many voters are motivated not so much by whether they think the projects will actually work, but more by their desire to say FUCK YOU to people like me (and probably you). The leaders of these movements (Trumpstick, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage) have acted cynically for their own benefit. They’ve been willing to stir division and nationalism. And some of their supporters are real racists. The only solution for that small minority is to be crushed and thrown into the dustbin of history. But I refuse to believe this is the case for the larger group of supporters, that is, half of the UK or almost half of the US. They have some legitimate concerns, and the only outlet to vent they were offered was a terrible one. If we want to move forward productively from these historical shocks (and please, let’s try to do that), rich world urban dickheads (like me) need to recognize that they are not the only people on the planet with views worth listening to.Perhaps it’s true that Labour also played a large role in the Brexit vote, but not in the way the rebellious MPs believe. As economist Mark Blyth explained in this video, what he calls “global Trumpism” is in part a response to the center-left turning its back on the working class. So if the Labour politicians want to point a finger at someone in their party, it’s wrongheaded at best to use Corbyn, the socialist activist with the largest portion of the working-class vote, as the scapegoat. If anything, as British singer Lily Allen tweeted to the Labour members of Parliament who, the day after the Brexit vote, had begun to accuse Corbyn of sabotaging the Remain campaign, “If anyone can lead [the U.K.] out of this darkness, it’s him, not you.” As I walked around London on Friday thinking about how this could become a “ProgrExit,” I heard a different buzz from the one I’m used to in this great metropolis — a more subdued, slightly frightened murmur of voices trying to make sense of the life-changing results of the referendum. I’d like to tell you they were asking the questions that Bevins is begging us “rich world urban dickheads” to consider about the inequality that is leading people to make desperate decisions. But they weren’t. They were talking about markets, corporations, the pound, talk that was echoed by Tories trying to “calm the markets” on Monday morning. That kind of talk isn’t going to move us closer to bridging the deep, painful rifts that threaten to break up the U.K. — the kind of talk none of us can afford as fascist forces rear their ugly heads. Now more than ever, we need Jeremy Corbyn at the helm of the Labour Party to chart a progressive way forward for Britain. Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.