Fidel Castro Is Dead at 90 (Video)

"Condemn me. It does not matter. History will absolve me," said the lawyer turned revolutionary leader before wrenching Cuba from the grip of the U.S.-backed authoritarian Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

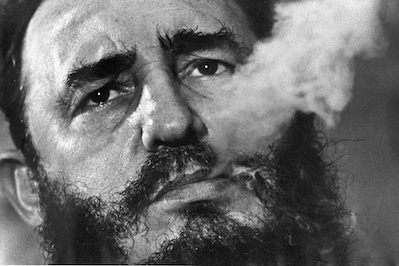

Fidel Castro. (Charles Tasnadi)

Cuba has declared nine days of national mourning after Fidel Castro, the revolutionary leader who in the 1950s wrestled the country from the grip of the U.S.-supported authoritarian Fulgencio Batista and survived more than 630 assassination attempts or schemes by the U.S. government, died Friday at age 90.

Batista, regarded as relatively progressive during his elected term as president from 1940 to 1944, seized power in a military coup in 1952 and canceled the country’s elections. Dictatorial and indifferent to popular concerns, he presided over high unemployment and infrastructure problems as he collaborated with organized crime and allowed American companies to dominate the Cuban economy.

Such was the trouble against which the young Castro — a lawyer and activist — his brother Raul, the Argentine rebel Che Guevara and thousands of others struggled, first legally, then militarily, until they finally ousted Batista in 1959. Those who attack without qualification Castro and the government he led after 1959 tend to ignore the fact that any nation seeking autonomy after World War II acted in a world dominated by a United States that was hostile to its aim. As Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer said, “Survival became the order of the day.”

Tariq Ali wrote in the book “The Declarations of Havana,” a collection of Castro’s speeches:

On 26 July 1953 an angry young lawyer, Fidel Castro, led a small band of armed men in an attempt to seize the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba, in Oriente province. Most of the guerrillas were killed. Castro was tried and defended himself with a masterly speech replete with classical references and quotations from Balzac and Rousseau, that ended with the words: ‘Condemn me. It does not matter. History will absolve me.’ It won him both notoriety and popularity.

Released in an amnesty in 1954, Castro left the island and began to organize a rebellion in Mexico. For a time he stayed in the hacienda that had once belonged to the legendary Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. In late November 1956 eighty-two people including Fidel Castro and Che Guevara set sail from Mexico in a tiny vessel, the Granma, and headed for the impenetrable, forested hills of the Sierra Maestra in Oriente province. Ambushed by Batista’s men after they landed, twelve survivors reached the Sierra Maestra and began the guerrilla war. They were backed by a strong urban network of students, workers and public employees who became the backbone of the 26 July Movement. In 1958 the guerrilla armies began to move from the mountains to the plains: a column led by Fidel began to take towns in Oriente, while Che Guevara’s irregulars stormed and took the central Cuban city of Santa Clara. The day after, Batista and his Mafia chums fled the island as the Rebel Army, now greeted as liberators, marched across the island into Havana. The popularity of the Revolution was there for all to see. Castro’s victory stunned the Americas. It soon became obvious that this was no ordinary event. Any doubts as to the Revolution’s intentions were dispelled by the First Declaration of Havana, Castro’s declaration of total Independence from the US made in public before a million people in Revolution Square. Washington reacted angrily and hastily, trying to cordon off the new regime from the rest of the continent. This led to a radical response by the Cuban leadership. It decided to nationalize US-owned industries without compensation. Three months later, on 13 October 1961, the United States severed diplomatic relations; subsequently, it armed Cuban exiles in Florida and launched an invasion of the island near the Bay of Pigs. It was defeated. President Kennedy then imposed a total economic blockade, pushing the Cubans in Moscow’s direction. On 4 February 1962, the Second Declaration of Havana denounced the US presence in South America and called for the liberation of the entire continent. Forty years later Castro explained the necessity for the Declarations:

“At the beginning of the Revolution … we made two statements, which we called the First Declaration of Havana and the Second Declaration of Havana. That was during a rally of over a million people in Revolution Square. Through these declarations, we were responding to the plans hatched in the United States against Cuba and against Latin America – because the United States forced every Latin American country to break off relations with Cuba … [These declarations] said that an armed struggle should not be embarked on if there existed legal and constitutional conditions for a peaceful civic struggle. That was our thesis in relation to Latin America. …”

While they were in the Sierra Maestra, the direction that the revolution would take was still not clear – even to Castro. Until that point, he had never been a socialist, and relations with the official Cuban Communist Party were often tense. It was the reaction of that noisy and powerful neighbour from the north that helped determine the orientation of the Revolution. The results were mixed. Politically, the dependence on the Soviet Union led to the mimicking of Soviet institutions and all that that entailed. Socially the Cuban Revolution created an education system and health service that remain the envy of much of the neo-liberal world. History will be the final judge, but Fidel Castro has already been elevated by a vast number of Latin Americans to the plinth occupied by those great liberators Bolívar, San Martín, Sucre and José Martí.

The Guardian reported Castro’s death as follows:

About widespread hatred of Castro in the U.S., the late American author Gore Vidal told Democracy Now! in 2008:

Well, I’m something of a fan of [Venezuelan president Hugo] Chavez. He’s just what certainly Venezuela needed, and he’s continuing in a sense the reforms of Castro. But you must remember, I know too much about media to be taken in by anything that most people read about Castro. “He’s got people in prison!” But yeah, a lot of rich people lost their money, and they’re very angry, so they exaggerate his crimes. But he never came up with Abu Ghraib. We did that, because we were fighting for democracy everywhere. So important to bring all this League of Nations together.

Nelson Mandela, the anti-apartheid revolutionary and president of South Africa between 1994 and 1999, was fond of Castro and called Cuba’s revolution “a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people.”

“We admire the sacrifices of the Cuban people in maintaining their independence and sovereignty in the face of a vicious, imperialist-orchestrated campaign,” Mandela said on a visit to Cuba in 1990. “We, too, want to control our own destiny.”

When Mandela died in 2013, Roque Planas wrote of the relationship between the leaders in an article titled “Why Nelson Mandela Loved Fidel Castro”:

The South African leader’s nationalist and anti-imperialist stances collided head on with the world’s superpower and gave him a lot in common with its Cuban archenemy. Mandela embraced the former Cuban dictator because he opposed apartheid and represented the aspirations of Third World nationalists that the United States undermined across the globe during the Cold War.

As it did for many leftists in the Global South, the Cuban Revolution’s triumph in 1959 inspired Mandela. Charged with the task of starting a guerrilla army in 1961, he looked to the writings of Cuban Communists for guidance.

“Any and every source was of interest to me,” Mandela wrote in his 2008 autobiography. “I read the report of Blas Roca, the general secretary of the Community Party of Cuba, about their years as an illegal organization during the Batista regime. In Commando, by Deneys Reitz, I read of the unconventional guerrilla tactics of the Boer generals during the Anglo-Boer War. I read works by and about Che Guevara, Mao Tse-tung, Fidel Castro.”

Mandela’s admiration for the Cuban Revolution only grew with time. Cuba under Castro opposed apartheid and supported the African National Congress — Mandela’s political organization and the current ruling party. Mandela credited Cuba’s military support to Angola in the 1970s and 1980s with helping to debilitate South Africa’s government enough to result in the legalization of the ANC in 1990.

The U.S. government, on the other hand, reportedly played a role in Mandela’s 1962 arrest and subsequently branded him a terrorist — a designation they only rescinded in 2008. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan vetoed the Anti-Apartheid Act.

Given this history, it shouldn’t be surprising that Mandela remained sharply critical of the United States into his later life. When the George W. Bush administration announced plans to invade Iraq in 2003, Mandela said: “If there’s a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America. They don’t care.”

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the British Labour Party, commented on the death of Fidel Castro:

“Fidel Castro’s death marks the passing of a huge figure of modern history, national independence and 20th century socialism.

“From building a world class health and education system, to Cuba’s record of international solidarity abroad, Castro’s achievements were many.

“For all his flaws, Castro’s support for Angola played a crucial role in bringing an end to Apartheid in South Africa, and he will be remembered both as an internationalist and a champion of social justice.”

At The Nation, Greg Grandin writes of the man who led “the joyful, raucous, and brash Cuban Revolution” and the discussion around him:

… In recent years, since he gave up power to his brother Raúl, Castro has dedicated himself to writing lengthy thought pieces, many of them on global warming, war, the fascism of neoliberalism, poverty, and other threats to humanity. Castro was a famous optimist and an irrepressible strategist, finding ways out of the grimmest situations (such as helping to nurture the coming to power of an electoral left in Latin America, which ended Cuba’s post-Cold War geopolitical isolation). His good friend, Gabriel García Márquez, once said Castro was a “sore loser” who would not rest until he was able to “invert the terms of the situation and convert defeat into a victory.” But, after having dodged by some counts 639 assassination attempts by Washington, Castro is finally at rest. …

There’s going to be a lot said about him in the coming days, and hopefully the recent thaw between Obama and Raul will permit a more generous assessment than what otherwise would have been on offer. A good starting place, for those wanting to go beyond the obits, would be the closest thing we have from Castro to an autobiography. About a decade ago, Castro did over a hundred hours of interviews with Ignacio Ramonet, published in English in 2008 as My Life. In it, Castro relates a story that captures his incongruities nicely: One of his earliest political memories, he tells Ramonet, is of the Spanish Civil War. His Galician father was a franquista, as were his Jesuit teachers, who prayed for Spain’s martyred priests. But he also learned of the Civil War, and what was being fought over, from Spanish nationalists. When asked by his family’s illiterate cook, a “fire-breathing Republican,” for news of the war, the 9-year old read him stories that played up loyalist success because he wanted to make him “feel better.” Thus Castro’s very first act of censorship was done in kindness.

Another story has Castro, in 1939, writing FDR to practice his English, requesting “a ten dollars green bill.” Roosevelt replied, but didn’t include the ten bucks, giving Castro a joke he’d use throughout his life: if FDR had paid up, then perhaps he wouldn’t have led a nationalist, anti-interventionist revolution. Nationalist resentment is sometimes built from fabricated grievances. Not in Cuba. In the late 19th century, rebels against Spanish rule forged an antiracist and democratic nationalism, only to be preempted by the United States’s 1898 invasion. Over the subsequent years, the US regularly intervened on the island—the Marines occupied it in 1906-09, 1912, and 1917-22—and just at the moment when FDR proclaimed his Good Neighbor Policy, his ambassador in Havana was openly working to oust a reformist president. Castro incarnated his generation’s finely tuned sense of anticipated betrayal and disappointment, animated by the spirt of New Left volunteerism, in a belief that the course of history could be bent to his will.

What about the “many other arguments to be had about Castro and the Cuban Revolution, about the relationship of political to social rights, about whether, considering the fate of other social democratic experiments in Latin America—in Guatemala, for example, or Chile—the Cuban Revolution would have survived had Castro not shut down civil society, and if that survival was worth it”? Grandin writes:

In My Life, Castro lists his country’s accomplishments in education and healthcare, advances in science and medicine, contribution to decolonization and defeating back [sic] white supremacy in Africa, ongoing humanitarian internationalism and the audacity of having survived “thousands of acts of sabotage and terrorists attacks organized by the government of the United States.” “What,” he asks, “is Cuba blamed for?”

The list is long, and over the decades the defense of the Cuban state has been, for many, deeply dehumanizing. And since Castro himself has repeatedly emphasized the importance of the individual in history—a “man’s personality can become an objective factor,” he once said—he will be held to account for the high cost involved in the revolution’s survival. And the most damning criticism leveled at the Cuban Revolution is not that it is repressive but that its repression was for naught, with all the old problems that plagued Cuba prior to the revolution having returned, including sex tourism, race-based economic inequality, and corruption—problems that will worsen if rapprochement is allowed to proceed.

In a segment titled “The Secret History of How Cuba Helped End Apartheid in South Africa,” Democracy Now! gives some of the reasons Mandela was grateful to Cuba and Castro:

The White House released a statement on Castro from President Obama:

At this time of Fidel Castro’s passing, we extend a hand of friendship to the Cuban people. We know that this moment fills Cubans – in Cuba and in the United States – with powerful emotions, recalling the countless ways in which Fidel Castro altered the course of individual lives, families, and of the Cuban nation. History will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and world around him.

?For nearly six decades, the relationship between the United States and Cuba was marked by discord and profound political disagreements. During my presidency, we have worked hard to put the past behind us, pursuing a future in which the relationship between our two countries is defined not by our differences but by the many things that we share as neighbors and friends – bonds of family, culture, commerce, and common humanity. This engagement includes the contributions of Cuban Americans, who have done so much for our country and who care deeply about their loved ones in Cuba.

Today, we offer condolences to Fidel Castro’s family, and our thoughts and prayers are with the Cuban people. In the days ahead, they will recall the past and also look to the future. As they do, the Cuban people must know that they have a friend and partner in the United States of America.

In an obituary at The Guardian, author and historian Richard Gott tells of the daring execution of the plot to overthrow Batista after Castro was released from prison and exiled to Mexico following his first attempted putsch:

Granted an amnesty two years later, Castro was exiled to Mexico. With his brother Raúl, he prepared a group of armed fighters to assist the civilian resistance movement. Soon he had met and enrolled in his band an Argentinian doctor, Che Guevara, whose name was to be irrevocably linked to the revolution. Castro’s tiny force sailed from Mexico to Cuba in December 1956 in the Granma, a small and leaky motor vessel. Landing in the east of the island after a rough crossing, the rebel band was attacked and almost annihilated by Batista’s forces. A few members of Castro’s troop survived to struggle up the impenetrable mountains of the Sierra Maestra. There they tended their wounds, regained their strength, made contact with the local peasants, and established links with the opposition in the city of Santiago.

Throughout 1957 and 1958, Castro’s guerrilla band grew in strength and daring. They had no blueprint. Their first aim had been to survive. Only later did revolutionary theorists develop the notion that the very existence of an armed struggle in rural areas might help to define the course of civilian politics, putting the dictatorship on to the defensive, and forcing squabbling opposition groups to unite behind the guerrilla banner. Yet that is what took place in Cuba. Civilian parties and opposition movements were forced to accept orders from the guerrillas in the hills, and even the conservative and unadventurous Communist party of Cuba eventually came to bow the knee to Castro in the summer of 1958. By December that year, Guevara had captured the central city of Santa Clara, and on New Year’s Eve, Batista fled the country. In January 1959, Castro, aged 30, arrived in triumph in Havana. The Cuban revolution had begun.

Castro’s program was one of “radical reform, comparable to that espoused by populist governments in Latin America over the previous 30 years. The expropriation of large estates, the nationalisation of foreign enterprises and the establishment of schools and clinics throughout the island were the initial demands of his movement.”

Gott describes the consequences of the United States’ hemispheric embargo on trade with Cuba after the U.S.’ failed Bay of Pigs invasion:

Although Kennedy had given a tacit promise to [Soviet premier Nikita] Khrushchev that invasion would never be repeated, the Americans continued to permit CIA-sponsored attacks on the island and refused to lift their economic blockade, pressurising the countries of Latin America to join in. Castro was effectively deprived of all contact with the US mainland, and later with most of Latin America. At first it was just fresh vegetables that Cubans could no longer obtain from Miami. Soon they were forced to abandon hope of receiving machinery and technology from the capitalist world. The oil blockade was particularly damaging. While the Soviet Union came to the rescue when oil could no longer be obtained from Venezuela or the Gulf of Mexico, the long journey from the Black Sea was hardly ideal. Their ships could carry no returning trade.

For a Caribbean island, rooted historically and geographically in the sea between the US and Venezuela, it was a cruel blow to lose the taproot of its commerce. Cuba had had previous experience of a monopolistic trade relationship, with Spain, its far-off madre patria, but the Soviet Union was even further away, and had little in common with Cuba except political rhetoric. The close Soviet link was to have a serious disadvantage in that it gave Cuba little opportunity to experiment economically. Guevara had hoped in the early days that the island might escape from the tyranny of sugar production and diversify its economy, but Castro perceived this to be an empty dream. Sugar was the only significant product Cuba could exchange for Soviet oil.

On Castro’s support for black liberation and his willingness to “fling” men and resources into foreign causes:

There was a further dimension. For Castro, Cuba was not just a Caribbean country with Hispanic connections. He was the first white Cuban leader to recognise the country’s large black, former slave population and, after initial hesitation, to make efforts to bring them into the mainstream of national life. Sergeant Batista, his predecessor, banned from Havana’s top clubs because of his mixed race, had secured considerable support from black people in the Cuban army, and Castro took up their cause. His championing of them came at the same time as the civil rights movement was growing in the US, and this may have contributed to the nervousness of the US government over his regime. On an early visit to the UN in New York, Castro stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, a symbolic but significant gesture.

Recovering Cuba’s black roots, both in the African slave trade and in the independence struggle of the 19th century, was a natural prelude to taking an interest in an Africa still in the throes of decolonisation. Cuban troops played a historic role in 1975 in rescuing Neto’s embryonic MPLA government in Angola from the South African army. Castro displayed a personal interest in the Angolan expedition, as he did two years later in Ethiopia, when Cuban soldiers were sent to assist the regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam. The Cubans helped the Ethiopians to push back the Somalis from the Ogaden. Castro’s boldness in flinging men and resources into foreign wars when Cuba itself was under permanent threat of attack was typical of his style.

And of the consequences of the loss of Cuba’s ally, the Soviet Union:

The policies of glasnost and perestroika espoused by Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s brought a dramatic unravelling of the Cuban revolution. Castro was always an opportunist communist rather than a true believer such as Erich Honecker, the East German leader, yet the two men shared a distrust of Gorbachev’s reforms. The stability and survival of their states depended on Russian support, although Cuba, the fruit of a popular revolution, had greater staying power than East Germany. Unlike some in the Cuban political elite who appeared willing to embrace changes in the Soviet system, Castro recognised that they would lead to disaster. For Cuba, the writing was on the wall even before the collapse of the Soviet Union after the failed coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. Castro knew that the US had made clear to the Russians, in 1990, that future economic assistance to the Soviet Union would depend on an end to Soviet aid to Cuba.

Castro declared a state of emergency, of the kind that would have been imposed had there been a military invasion. His political genius was for improvisation and compromise, coupled with a verbal felicity that proved capable of persuading people that he was doing one thing when actually doing another. He now projected Cuba as the world’s first truly “green” society, with industry powered by windmills, and the people riding bicycles. It was guerrilla war all over again, with Castro invoking the spirit of the Sierra Maestra.

Then, before any significant change could be made to the Cuban system, the Soviet Union imploded, and with it went the extensive economic network that it had maintained. A form of perestroika had now to be forced on the Cubans whether they wanted it or not, for Castro’s ally had simply melted away. Boris Yeltsin, the new Russian leader, was no friend. He had even visited Jorge Mas Canosa, the principal organiser of the Cuban exiles in Miami, and he soon removed Russian soldiers from the island and abandoned most of the preferential economic agreements that had kept the Cuban economy afloat for so long. Hopes in the US that Cuba would go the way of the countries of eastern Europe were encouraged by legislation in Congress that sought to tighten the economic embargo.

Read Gott’s full obituary here.

Ignacio Ramonet, who co-wrote Castro’s autobiography after interviewing him for 100 hours, reflects on the life of the “excessively respectful” intellectual who succeeded in bringing Latin America onto the international stage:

Here’s an excerpt of a speech Castro gave at a U.N. summit in New York on Sept. 7, 2001:

There is chaos in our world, both within the countries’ borders and beyond. Blind laws are offered like divine norms that would bring peace, order, well-being and the security our planet so badly needs. That is what they would have us believe.

Three dozen developed and wealthy nations that monopolize the economic, political and technological power have joined us in this gathering to offer more of the same recipes that have only served to make us poorer, more exploited and more dependent.

There is not even discussion about a radical reform of this old institution — born over a half-century ago when there were few independent nations — to turn into a true representative body of the interests of all the peoples on Earth; an institution where no one would have the irritating and anti-democratic right of veto and where a transparent process could be undertaken to expand membership and representation in the Security Council, an executive body subordinated to the General Assembly, which should be the one making the decisions on such crucial issues as intervention and the use of force.

It should be clearly stated that the principle of sovereignty cannot be sacrificed to an abusive and unfair order that a hegemonic superpower uses, together with its own might and strength, to try to decide everything by itself. That Cuba will never accept.

‘A moral and humane world with liberty and progress.’

Cuban exiles in Miami celebrated the death of Castro:

At The Guardian, columnist Will Hutton observes of Castro’s effect on him as a youth and the repression that was part of Cuban life before, during and after Castro’s reign:

We did dance for liberty and freedom. But we also danced for a world in which, as Fidel proclaimed, we looked out for each other. Most Cubans want to retain the great egalitarian legacy he has left, even while they try to combine it with a more dynamic economy and genuine political freedoms. The dream remains to combine all three. I dreamed it then. I dream it now.

Also at The Guardian, Simon Tisdall writes:

It will never be known whether, without the crushing effect of the US embargo, the Cuban revolution might eventually have flourished economically and liberalised politically. Certainly Castro felt himself under permanent siege, in an ongoing state of war, and this inescapably constricted his policy choices. As the infinitely more powerful and wealthier partner in a dysfunctional relationship, he certainly believed it was the US that bore the greater blame. …

In a sense, Castro’s entire life’s work may be summed up in this way: agree with his views or not, condone his methods or fiercely dispute them, he fought indefatigably against tremendous odds throughout his political life – and in so doing achieved an astonishing degree of influence across the globe. Maybe his legacy will stand the test of time, as he claimed at April’s congress, or maybe not. But for the most part, Castro, iconic hero of the left, was on the right side of history.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.