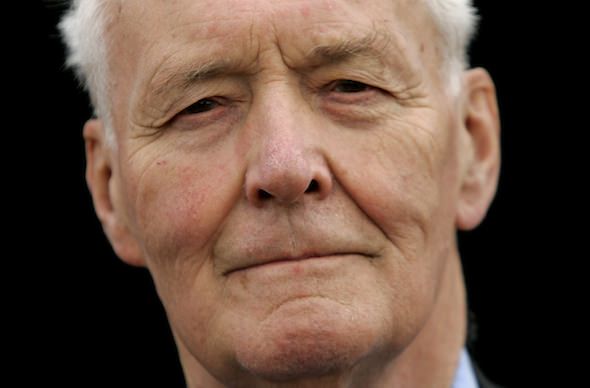

British Socialist MP Tony Benn Dies at 88

The Labour parliamentarian was a leader who seemed too good to be true for everyone in the bottom 90 percent of the economy in Britain and everywhere else. Here is a collection of statements made by and about him.The Labour parliamentarian seemed too good to be true for everyone in the bottom 90 percent of the economy in Britain and everywhere else.

Labour parliamentarian Tony Benn, “lodestar for the Labour left for decades, orator, campaigner, diarist and grandfather,” The Guardian wrote, died in his home surrounded by family Friday. He was a leader who seemed too good to be true for everyone in the bottom 90 percent of the economy in the U.K. and everywhere else.

Born into the British aristocracy, Benn renounced his hereditary peerage and became one of the most passionate, principled and respected avowed socialists and representatives of the public’s cause in the latter half of the 20th century. Shami Chakrabarti, director of the British civil liberties advocacy group Liberty, was quoted in The Guardian’s obituary of Benn as saying: “In an age of spin, he was solid, a signpost and not a weathervane.”

On Friday, Guardian correspondent Gary Younge eulogized Benn thusly: He “believed that people were inherently decent and that they could work together [to] make the world a better place — and he was prepared to join them in that work wherever they were.”

An unwavering devotion to the welfare of society’s disadvantaged earned Benn the honorable appellation of political divider. But “[w]hat some refuse to forgive is not so much his divisiveness as his apostasy,” Younge said. “He was a class traitor. He would not defend the privilege into which he was born or protect the establishment of which he was a part. It was precisely because he knew the rules that he would not play the game.

“He hitched these principles to Labour’s wagon from an early age. Its founding mission of representing the interests of the labour movement in parliament was one he held dear. He never left it even when, particularly as he got older, it seemed to leave him. His primary loyalty was not to a party but to the causes of internationalism, solidarity and equality, which together provided the ethical compass for his political engagement. When people told him that they had ripped up their party membership cards in disgust, he would say: ‘That’s all well and good. But what are you doing now?’

“The devotion that has poured out for him since his passing is not simply nostalgia. The parents of many of those who embraced him in recent times — the occupiers, student activists, anti-globalisation campaigners — were barely even conscious at the height of his left turn. They are not mourning a relic of the past but an advocate for a future they believe is not only possible but necessary.”

Elsewhere on The Guardian’s site, Benn’s colleague and editor Chris Mullin told of how his friend might have beat Margaret Thatcher in the race for prime minister if certain moments of history had gone differently.

“There was a moment — just a moment — in September 1981 when one caught a glimpse of what might have been,” Mullin wrote. “Despite the ferocious onslaught to which he had been subjected, pundits began to predict that Benn might win the hard-fought election for the deputy leadership and that his rise to the leadership was only a matter of time. Suddenly the centre ground began to shift. A respected political correspondent on a national newspaper offered me a job. ‘The Labour right is all washed up,’ he said. ‘I feel like a journalist in apartheid South Africa whose only contacts are with the regime; I need to make contact with the other side.’ Also, I received a call from a Labour MP who would later be a prominent member of Tony Blair’s government. ‘I just want you to know,’ he said, ‘that I will be voting for Tony and I think I can bring one or two others with me.’ He added that he had put £50 on a Benn victory. In the event, Benn lost by a whisker and from that moment on his star waned.

“To this day I am one of that small club (and I appreciate it is a small club) who believe that had Benn defeated [Denis] Healey in 1981 and gone on, as many expected, to become Labour leader, the Labour party would never have sunk to depths that it did in the early 1980s. Although the Falklands factor would still have ensured a Thatcher victory in 1983, she would have faced a much more formidable and coherent opposition and might conceivably have been defeated in 1987.

“But the tide of history was running strongly in the opposite direction and by the late 80s Benn had drifted into impossibilism. In 1988, against the advice of his beloved wife Caroline and just about all his friends, he challenged Neil Kinnock for the Labour leadership, obtaining just 12% of the vote. Later, under Blair, his base narrowed even further. The scale of his opposition to the Blair government and just about all its works was exhausting. Wearying even to read about, never mind to live through.”

Below, see Benn in full oratory force in four videos. In one, he tells how neoliberalism arrested England’s full evolution into the democracy it set out to become after World War II. (“The restoration of power of those who’ve always controlled the world, the people who’ve owned the land, the resources and all the rest of it.” That’s what he says British economic policy of the last three decades is about.)

In an interview taken from Michael Moore’s “Sicko,” Benn tells the story of the British people’s decision to provide health care to everyone in a time when their economy was trashed. In an interview with comedian Ali G, he bats away what have come to be standard criticisms of left-wing values and emerges with his dignity intact. And in the last long clip, he inveighs against imperial war and economic exploitation in four powerful speeches to parliament.

— Posted by Alexander Reed Kelly.

MetaReaLizard:

Michael Will:

Muig:

Lincoln Farquharson:

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.