TD Original

TD Original

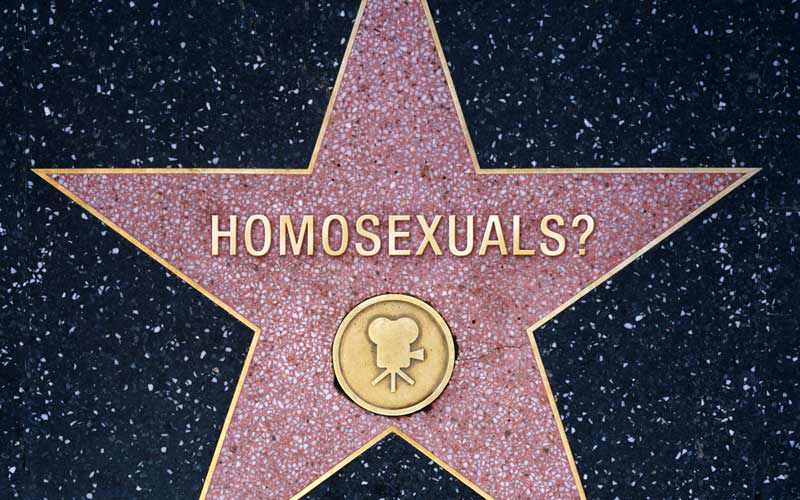

Year of the Queer: Hollywood and Homosexuality

Feb 27, 2006 Truthdig's Larry Gross, a pioneer in the field of gay studies, argues that for all the hoopla surrounding "Brokeback Mountain" and this year's spate of gay-themed films, there is little about them that upends Hollywood conventions or challenges popular ideas about homosexuality. "Hollywood and much of the media may be awash in liberal self-congratulation," Gross writes, "but they--and we--are also soaking in the familiar hypocrisy of homophobia." Update: Down to the WireGross argues that for all the hoopla surrounding "Brokeback Mountain" and this year's spate of gay-themed films, there is little about them that upends Hollywood conventions or challenges popular ideas about homosexuality. 1 2 3 4 5Once it's been clearly established that the actors playing gay roles are not themselves gay, the next step in Hollywood's recipe for gay themes is to push the universalism button. In other words, not only are the actors not really gay, but neither is the story. It's not enough, apparently, that the audience can safely know that it's not harboring romantic fantasies about an actor who's really batting for the other team, we must also be assured that we're not being emotionally engaged and moved inappropriately.

For a long time it has been obligatory for any gay-themed movie to be presented as universal, in order to appeal to the often mythical crossover audience. When William Wyler made the second film version of Lillian Hellman's "The Children's Hour" in 1961 -- the first version, "These Three," also directed by Wyler, in 1936, transmuted homosexuality into adultery -- Wyler was quoted: " 'The Children's Hour' is not about lesbianism. It's about the power of lies to destroy people's lives." This line was later echoed by Rod Steiger in 1968 (" 'The Sergeant' is not about homosexuality, it's about loneliness") and Rex Harrison in 1971 (" 'Staircase' is not about homosexuality, it's about loneliness") about their gay roles, and by director John Schlesinger about his 1972 film (" 'Sunday, Bloody Sunday' is not about the sexuality of these people, it's about human loneliness"). Even more ridiculously, in the lead-up to the 1982 "breakthrough" studio "gay film" "Making Love," written by openly gay screenwriter Barry Sandler, producer Allan Adler was quoted, "We're not anxious to have 'Making Love' defined as a gay movie." Talking about the story of a doctor who comes out of the closet and leaves his wife for another man, Adler said, "We hope that it will be seen as a love story. It's not a slice of gay life."

This is an old and familiar strategy, much loved by critics as well as publicists. The pattern was set by reviewers critiquing gay playwrights and novelists. Heterosexual critics find fault with gay artists for not rising above their parochial concerns, that is, for addressing themselves to the concerns of their fellow gay people. In a 1980 letter to The New York Times Book Review, justifying his negative review of Edmund White's "States of Desire: Travels in Gay America," critic Paul Cowan asserted that "it's crucial to communicate across tribal lines. Good literature has always done that -- it has transformed a particular subject into something universal. Mr. White didn't do that: in my opinion it's one of the reasons he failed to write a good book." Novelist David Leavitt was felled by the same ax, wielded by New York Times reviewer Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, when Leavitt published his first novel, "The Lost Language of Cranes," in 1986. Lehmann-Haupt seemed quite sympathetic to the novel, and congratulated Leavitt for creating explicitly homosexual characters, thus enabling the critic to "discern a resolution to the old debate over whether or not homosexual art is inherently limited." In other words, parochial, not universal. And, no surprise, Leavitt didn't quite pass the test, perhaps because he was "subtly biased in favor of [a homosexual character's] outlook." Better luck next time.

In contrast, when a gay writer is praised, artistic success will be defined as having achieved universalism. Lehmann-Haupt, ever vigilant on the ramparts of literature, was more charitable toward Edmund White's 1988 novel, "The Beautiful Room Is Empty," but no less focused on the main question. His review opened: "The subject is homosexuality in Edmund White's new novel.... There are in the book explicit scenes of lovemaking. So the question is immediately posed: Is this a novel of parochial appeal, or can anyone, regardless of sexual preference, appreciate it?" Fortunately for White, he passed the test, if only barely, as "there is much in [the novel] that makes one uncomfortable, if only because it is so specific in its sexual appeal." The novel concludes with the narrator witnessing the Stonewall riots, and Lehmann-Haupt concluded his review: "Gay liberation has arrived; it is their Bastille Day and we find ourselves cheering, even in the face of what we know is to come -- and what Mr. White must surely write about in another sequel. Such is the subtlety and strength of [the novel] that we actually find ourselves cheering." Note that "we" who are cheering are clearly not gay, even though gay people read The New York Times. And note that "what we know is to come" -- AIDS, of course -- somehow in Lehmann-Haupt's mind casts the value of gay liberation in doubt.

In 1993 playwright Tony Kushner astonished the theatrical world with the success of his epic, "Angels in America," winning Pulitzer and Tony awards and selling out theaters for a two-part, seven-hour "gay fantasia on national themes" (as "Angels" was subtitled). Critics were predictably quick to see Kushner's work in a broader, dare we say, universal light. Writing in the Chicago Daily News under the appropriate headline "Angels reaches beyond gay issues," Richard Christiansen offered a representative sample:

Some of the reason for Kushner's success can be attributed to the strength of his voice as a member of the increasingly vocal gay community of this country. Angels springs directly from a gay political, social and sexual culture, and it expresses that culture with pride, force and eloquence.... But Angels in America, which roams across heaven and earth in its fantasy, is considerably more than a well-written gay play. For the first time in years, an American playwright has succeeded in painting on a broad canvas, exploring "national themes" on a grand scale.... Much of its story is necessarily bleak, dealing with death by AIDS, but the play is also an amazingly vibrant and joyous work, celebrating not only the gay spirit but the eternal resilience of a confused and besieged humanity.

Perhaps good literature has always transformed a particular subject into something universal. But there is always a double standard in the application of the universalism criterion. And, needless to say, gay artists are not the first to have been put to the test. In an essay on "Colonialist criticism," the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe decried those Western critics who evaluate African literature on the basis of whether it overcomes parochialism and achieves universality: "It would never occur to them to doubt the universality of their own literature. In the nature of things, the work of a Western writer is automatically informed by universality. It is only others who must strive to achieve it."

In a particularly condescending example of the universalism ploy, critic Mary McCarthy wrote "A Memory of James Baldwin" in 1989 in which she congratulated herself for appreciating Baldwin as her "first black literary intellectual." What she means by this is explained as follows: "Baldwin had read everything. Nor was his reading colored by his color -- this was an unusual trait." Whether Baldwin thought McCarthy's readings were colored by her color we're not told. A similarly blatant example of racist universalism was reported in 1989 by Michael Denneny, who "watched an almost classic liberal, Bill Moyers, on his television show ask [Pulitzer prize-winning African American playwright] August Wilson, 'Don't you ever get tired of writing about the black experience?' " As Denneny says, this is a question of breathtaking stupidity that makes one wonder if Moyers would ask John Updike he ever tires of writing about the white experience. But, of course, we know the answer: Moyers probably equates "the white experience" with life itself; that is, it's universal.

It comes as no surprise, then, that it's not only Gyllenhaal and Ledger who push the universalism button when surveying "Brokeback Mountain." A chorus of critics proclaims the film's accomplishment in rising above the muck of gay particularity and ascending to the heights of universal humanity. What a relief.

American novelist Rick Moody's article about "Brokeback Mountain" in London's Guardian is headed "Brokeback Mountain is far more than a gay western. It's a great American love story," and it proclaims:

The magnificent thing, though, that happens during the unravelling marriages of these two men, as the film hastens toward its heart-rending completion, is that you stop thinking of these men as men, or gay men, or whatever, and you start thinking about them only as human beings, people who long for something, for some kind of union they are never likely to have.

In The New York Times, Caryn James, who has already noted that our awareness that the actors are straight "makes it easier and maybe more acceptable for middle-class heterosexual viewers -- a group that does, after all, include most of us in the audience -- to embrace characters whose sexual preferences we don't share," assures us the story "resonates with the emotions attached to any love facing insurmountable obstacles."

It's not only mainstream, heterosexual writers who are determined to cast this particular story in a broader frame. Salon.com's Scott Lamb quotes Damon Romine, entertainment media director for the lesbian and gay media advocacy group GLAAD: "At its most basic level, this is a story about relationships," he says. "The love that these characters experience in many ways transcends categories of gay and straight; this is a universal love story." Gay writer Jim Fouratt informed the readers of his Web postings, "Please do see the movie and suggest to your friends who might not that they in fact do and go with an open mind. Brokeback Mountain is not a 'gay' movie. Brokeback Mountain is a 'human' movie for all."

In a similar vein, gay historian Eric Marcus tells Ryan Lee of Houston's gay paper, "It's absolutely a universal love story -- a love story about two gay men. My vote is that Jack and Ennis are gay, and there was never any doubt in my mind." Interestingly, Marcus was responding here in part to the objection raised by bisexual activists that the characters, who marry and have children, are more accurately defined as bisexual, even though their magnetic poles are oriented toward each other.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.