You Say You Want a Revolution? Young Americans to Bernie Sanders: Count Me In!

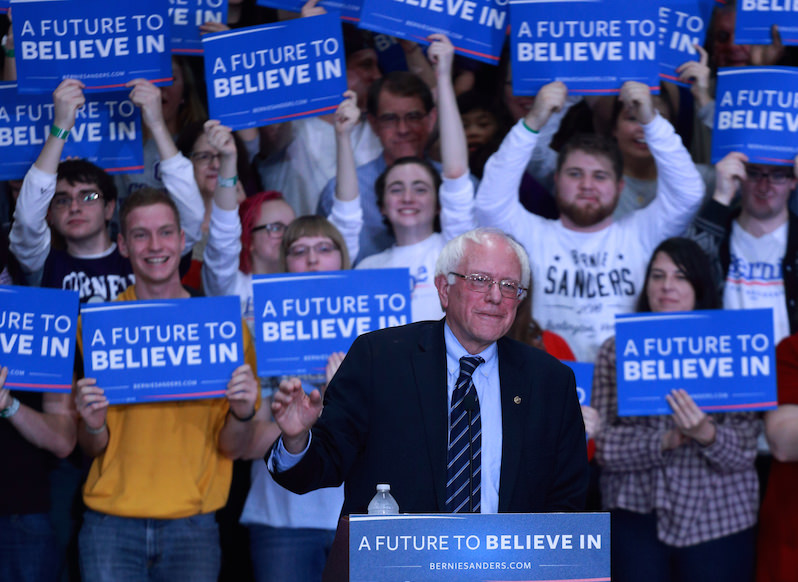

Bernie Sanders' youth-powered bid for the presidency is more than just a campaign: It's a reflection of a rising passion among Americans for a new political life. Sen. Bernie Sanders rallies young voters at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. (CJ Hanevy / Shutterstock)

Sen. Bernie Sanders rallies young voters at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. (CJ Hanevy / Shutterstock)

By Alan Minsky

If you were in Iowa this week, you would have been willfully blind not to recognize a simple fact: Young Americans want things to change, and their chosen catalyst is Bernie Sanders.

This was confirmed Monday night at Democratic caucuses across the state: The respected elders moved to one side for Hillary Clinton, the revolutionary youth to the other for Sanders.

Sanders’ message that resonates with the youth recalls the Occupy movement: The reign of Wall Street, the age of greed, has lasted more than three decades; it’s had its chance to make good. If you’re among the wealthy few and have no conscience, the results are brilliant; but for the vast majority (the 99 percent), it’s rotten or worse. So, now is the time for a progressive, social revolution informed by the better angels of our nature. This means a more economically equitable society, a revitalized democracy free of the influence of big money, an end to centuries of racist oppression, sexism and homophobia and an unwavering commitment to combat global warming by moving to 100 percent renewable energy.

They say they want a revolution! So, “What is to be done?”

Simple. Sanders must defeat Clinton for the Democratic nomination, go on to win the presidency and, in the process, build a participatory movement that transforms this society and the world.

More precisely (these youth are a practical lot), the immediate goal is to build on Iowa with a succession of strong performances by Sanders over the next month. This entails winning New Hampshire, then doing sufficiently well in Nevada and South Carolina that the success carries over. This would ensure that Sanders is not blocked by Clinton’s big “firewall,” the set of primaries, many of them in the Southeast, on Super Tuesday. To achieve these ends, Sanders has to gain support in communities of color and also with senior citizens—all the while building on his core message of taking back the country from greedy oligarchs to achieve a more equitable society with shared prosperity, a vibrant democracy and greater liberty for all.

* * *

I just spent six days in Iowa, dutifully attending other candidates’ rallies and learning much about Iowa and the caucuses (the story behind their creation after the 1968 Democratic debacle is fascinating). But my focus was primarily on one thing: the Sanders campaign, why it was doing so well, and how it could do even better.

On my flight out of Des Moines, I asked a young member of the Clinton campaign why she thought Hillary had won older voters so decisively. She suggested that older voters were more realistic and would understand that Sanders would be unable to get his ambitious agenda through Congress. She thought some were worried that a Sanders victory could lead to problems such as stock market turbulence. She added that older women felt that a Clinton victory would be the only chance in their lifetime to see a female president.

It is fair to say that the concerns of older Americans have not been a primary focus of Sanders’ campaign speeches. Given his poor showing with seniors in Iowa, that needs to change, especially given his strong advocacy on issues that concern them.

In marked contrast to the Clinton/Obama wing of the Democratic Party, Sanders calls for the expansion of Social Security. The party has been willing to lower payments to recipients to cut costs and, on occasion, even advocated some form of (potentially catastrophic) privatization—a holy grail for Wall Street.

On the campaign trail, Sanders is proving to be a master at succinctly communicating the significance of economic policies. As such, he should be able to drive home that he alone is the true protector of Social Security—an assertion that should be tremendously popular with older voters. Sanders promises to keep the system fiscally sound for the foreseeable future by eliminating the limit on income that is taxed for Social Security, so that high-income earners pay the same percentage into the system as everyone else. Not only would this keep the system well funded, it would allow for an increase in payments to recipients. Nothing should be more important to older Americans (especially low-income seniors).

If that isn’t enough to distinguish him among senior citizens, Sanders’ call for single-payer health care can be delivered with many emotionally riveting examples of how this policy would vastly improve their lives. Nothing is more anxiety-inducing than the for-profit American health insurance complex. Under Sanders’ plan there would be no denial of coverage; no paperwork nightmare that can generate life-threatening delays; and, most significantly, no risk of exorbitant costs. In fact, it would be virtually free. And Sanders needs to make it clear that he poses no threat to existing programs; he seeks only to improve the system and, if he’s unable to achieve that through legislation, is committed to preserving the existing system of Obamacare.

If Sanders incorporates these two points—on Social Security and single-payer health care’s advantages for seniors—into his stump speech, and delivers them with the rhetorical force of his critique of Wall Street, he should be able to win the support of a much higher percentage of seniors than he did in Iowa.

One other point the young Clinton staffer made, however, might inform Clinton’s lead over Sanders among older voters. Younger people in our society are not accruing wealth as in previous generations. Consequently, wealth is concentrated in the hands of older people. If Clinton represents continuity and Sanders proposes to shake things up, it is not surprising that she leads in this demographic. Therefore, when Sanders tries to win over older Americans to his revolution, he could place greater emphasis on a key aspect of his economic program: that re-allocating money into the hands of people who will spend it (average working people, not the super-wealthy) will, through the multiplier effect, generate a more prosperous overall economy. Well-off older Americans need not fear that the Sanders agenda will create an economic downturn that could see their wealth evaporate.Sanders should assure older voters that he doesn’t represent a threat to their well-being and livelihood and is promoting policies that would improve their lives. If he does this with his standard passion, it should be a winning hand.

After the caucus results came in, I discussed the events with a large group of politically engaged Iowans in the front office of KHOI Radio in Ames. Just about everyone wore a Bernie sticker, and the group was in good spirits. There was consensus that the Iowa virtual tie meant that Sanders remained the candidate with momentum and would probably continue setting the terms of the debate. But everyone also understood that Sanders had to break through with black and Latino voters, or Clinton was going to wrap up the nomination very soon.

When it comes to Clinton’s infamous “firewall”—an alliance of the black and brown political establishment, nonprofits and voters fiercely loyal to the Democratic Party and the Clintons—Sanders, a white man from a virtually all-white state, has a distinct disadvantage. He trails in the polls in both states, but recent gains in South Carolina and Nevada provide a glimmer of hope that his message is beginning to resonate with black and brown voters.

Between now and the Feb. 20 caucus in Nevada and the South Carolina primary a week later, Sanders has to drive home how the revolution he’s calling for will dramatically improve the lives of people of color—who have suffered centuries of oppression in America’s brutally exploitative race/class system. Sanders has been put under a considerable amount of constructive pressure by black activists and commentators over the past few months. Much of the criticism has centered around the notion that while Sanders has a strong program that addresses economic inequality, he’s weaker on the institutionalized racism made tragically clear by the frequent killings of unarmed black people by police.

Sanders can respond to this criticism in two ways. The first would revolve around his economic message, but with a focused elaboration on its significance for communities of color. He could frame it in the context of the stunning “racial wealth gap” that has always existed in the United States and currently stands at approximately 13 to 1. In other words, the average accumulated wealth of black households in America is just above $10,000—compared with about $140,000 for white households.

Sanders knows these facts. They are even buried in a section of the FeelTheBern website—but I’ve never heard him bring the issue to the foreground during this campaign cycle. It is a powerful, take-your-breath-away argument: the brutally unjust imbalance made evident by the statistics. He could highlight the reality that this racial wealth gap has remained a constant in post-war American society, and that neither Clintonomics nor Obamanomics have significantly improved the situation.

In contrast, Sanders’ array of proposed economic programs—what he’s called democratic socialism, rooted in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights—would rectify this inequality more effectively than any national economic program in U.S. history. (Sanders is running to be a transformational president; he shouldn’t be shy about announcing it.).

His program is designed to raise real household wealth for poor, working-class and middle-class households (thus, the large majority of black households) so that the wealth gap will close dramatically. Sanders also seeks to make reforms to sectors of the financial services industry (issuers of high-interest credit cards and payday lenders) that prey on poor and working families; as well as introducing non-predatory lending institutions in communities without them, which can facilitate both small business development and more home ownership—still the best instruments to close America’s disgraceful racial wealth gap. Such policies also would dramatically increase the financial security of Latinos, whose average household wealth is only slightly higher than that of black Americans.

Last month, influential author Ta-Nehisi Coates criticized Sanders’ unwillingness to support calling for reparations. I believe that if Sanders explains his economic program in the context of the racial wealth gap, it will allow him to re-address the matter of reparations. While Sanders’ programs could do much to shrink the gap, to close it completely—which would of course be the stated goal—would probably require supplementary measures, one of which could be reparations. Such framing of the issue would give Sanders the opportunity to endorse Rep. John Conyers’ bill, HR 40—which Coates supports as a baseline position. The bill merely calls for the creation of a congressionally sanctioned body to study the issue.

Reparations, or any direct payments to poor communities, would work better after the economic changes proposed by Sanders are enacted. When a substantial amount of money is paid to households in debt, it’s helpful but likely to disappear rapidly. But direct payments to households—in a society that has free colleges, single-payer health care and community investment institutions in place of payday lenders and predatory banks—are more likely to stay where they’re intended, as part of a household’s accumulated wealth. Sanders must convey to the black community that his radical re-alignment of the priorities of the American economy is designed to address the grave sins of history that have produced this economic imbalance. Such an approach would be his best chance to make a powerful, positive impression on black voters.Sanders also should state unequivocally that institutionalized racism in America must be addressed as a separate subject from economic injustice. He should make a strong declaration of his intentions—such as committing his Justice Department to investigating the criminal justice system in order to expose and root out systemic racism. It remains a tragic truth that, too often, equality before the law does not yet exist in America. Sanders has to convey that a goal of his transformational presidency, and his political revolution, is a quantum shift in American race relations, ending the era of the “New Jim Crow” and creating a just, economic balance.

The persistent critique of Sanders is that he has little chance of enacting these proposals into law. But he has always said he cannot do it alone; it will take a movement. In recent weeks, the Sanders campaign has incorporated some beautiful messaging around this idea: the #NotMeUs hashtag that trended worldwide on Twitter a couple of days before the Iowa caucus, and the “Together” TV spot. It would be great to see Sanders build on this. He could take a page from the 1988 Jesse Jackson campaign (which he famously endorsed) by openly inviting social justice movements into the campaign—making it clear that the Sanders revolution will be responsive to the needs of real people.

A successful revolution needs all the allies it can have, and Sanders has proved surprisingly popular among white, working-class Republican voters—something that was consistently reported in the Iowa press, albeit anecdotally. From the beginning of the campaign, he’s made it clear that he intends to appeal to this constituency (witness his visit to Liberty University), which he recognizes is being manipulated by the GOP. Sanders could point out that the Republican Party never enacts the social agenda of its conservative base (Roe v. Wade is still law, thank goodness), but rather serves the economic elites to the detriment of average American households. Sanders will not help white, working-class Republican voters achieve their social agenda, but they would certainly be better off supporting his candidacy over that of some GOP front for the interests of the “1 percent” (such as Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, or Ted Cruz) that exploits them with false promises.

Similarly, Sanders can present himself as the champion of something with almost universal appeal: an America vibrant with small, family-owned businesses, much like those that flourish in Burlington, Vt., where Sanders was mayor during the 1980s. While in Iowa, I spent my days in Ames at a community radio station surrounded by small shops and businesses that were overflowing with Sanders supporters. It is clear that the young, revolutionary generation yearns for a world full of the character and human feel of small, family businesses, and not the antiseptic homogeneity of corporate chains. Sanders should remind the country that he is a wily legislator and former mayor of a small city who knows how to help small businesses—in marked contrast to Clinton or the GOP. He is the opponent of what has really been the people’s greatest adversary: the leviathan of multinational, corporate capitalism.

Iowa showed the raw power and potential of Sanders’ vision to inspire and mobilize people; but it is a long hard road to the Democratic nomination. If Sanders makes this array of arguments over the coming month, his campaign—which represents the greatest electoral challenge to the powers that be in our lifetimes—will have played its best hand.

If Sanders remains highly competitive into early March, there will be a world to win. Until then, it makes little sense to focus on any electoral contests other than the presidency, which will certainly consume all of the campaign’s energy and resources. By early March, however, it will be necessary to signal that this is much more than an effort to elect one man as president. There is a tremendous appetite in America for fundamental changes in our economic and social organization, in the service of greater social justice; but these changes cannot come from the executive branch alone. Sooner or later, Sanders is going to have to outline how this movement can win a majority of allies in both houses of Congress, as well as elect like-minded politicians across the country at the state and local levels. Judging by the youth of Iowa, a voracious appetite for such an achievements exists. Before the end of spring, the campaign must make this goal clear.

After all, the Sanders campaign may resemble movement activism, but it is an electoral campaign; albeit one that is seeking to make structural social change by winning elections and altering public policy. The Guardian’s Gary Younge recently showed how electoral victories by the left in Europe did not lead to the scope of changes their supporters expected. Similarly, if you look at the history of the last century, elected politicians have rarely been the primary agents of change in America. Even in the case of FDR’s transformational New Deal legislation, it’s hard to imagine it passing without a powerful labor movement winning victories amid the social dislocation of the Great Depression. Certainly, the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements were not led by politicians; and, at best, elected officials have been allies of the contemporary LGBT movement.

So Sanders is swimming against the tide by staging an insurrection inside the two-party system—and as Younge points out, the recent spate of victories by unapologetically left political parties (Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, the left coalition in Portugal and Jeremy Corbyn in the British Labour Party) has yet to have any significant impact on economic policy in those countries. It’s a point which seems to support the radical left’s traditional position that engagement with electoral politics is a waste of time and energy. Perhaps, but the already spectacular number of people participating in the Sanders campaign, and the fact they’re engaged—with questions like, “What do we need to change in society to make it more equitable?”, “How do we make those changes?” and “What do we change it into?”—is by itself an achievement in contemporary America. And, happily, it’s not just a parlor game; word has leaked out from the oligarch’s lair (Davos) that the Sanders campaign is a mortal threat to their rule!

Lastly, as we look starry-eyed at something many of us thought we would never see—a radical challenge to the inflexible rule of capital over American life and the corrupt electoral system—we should harbor no illusions that anything has really changed. If Sanders has continued success and threatens to win the nomination or presidency, rest assured he will meet with opposition much greater than anything even Hillary Clinton has in her arsenal. It’s an unspoken dictum that any policy enacted by the government—no matter how much it claims to benefit ordinary Americans—must not only deliver more gains to the people and institutions that own the vast majority of wealth in our society, but also must never challenge the political and social power of this privileged minority. Anyone who suggests otherwise will be facing off against the wealthiest and most powerful foes on the planet.

Given that we are in our fourth decade of ever-increasing consolidation of wealth and power at the top, it’s not surprising that many feel the Sanders revolution is a quixotic quest; but Cervantes’ hero—like ours, with the heart of a true, chivalrous hero—saw monsters where there were windmills. Whereas our heroes, the youth of America, the activists across the land, and a politician actually trying to do what’s right—see the real monsters behind the ever-widening breach in the American dream, those who take all the gains for themselves and subject millions to debt peonage or worse.

Bernie Sanders has opened the door; and we may have a once-in-a-lifetime shot at changing our collective fate. But it’s up to his allies, all of us, to stay engaged with the movement and help it grow. The goal is to win the presidency, but that is only a means to an end: What Bernie wants is an opportunity for all of us to forge a new and better world. That’s the revolutionary agenda for 2016.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.