Will Trump Repeat the Historic Chinese Exclusion Act Mistake?

The president’s executive orders hurl America back to 1882, when Congress passed a law barring immigration based on a specific race and national origin.

By Judy Yung

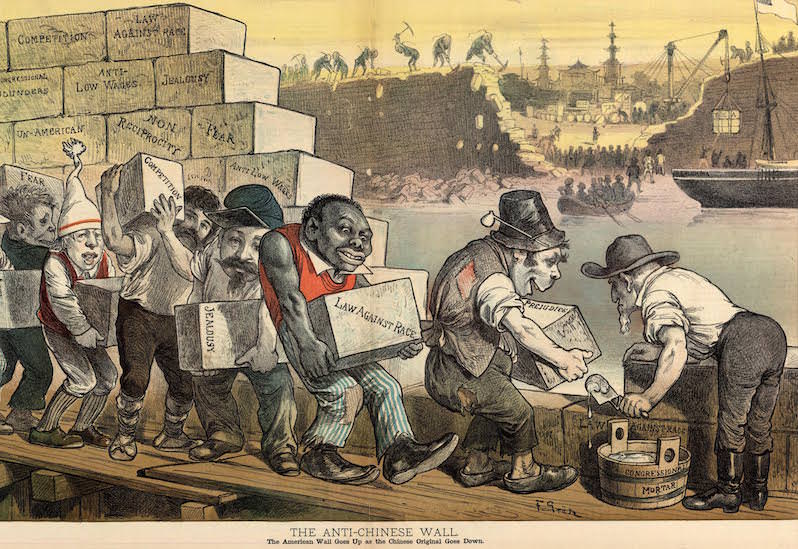

“The Anti-Chinese Wall—The American Wall Goes Up as the Chinese Original Goes Down,” by Friedrich Graetz, Puck, 1882. (Library of Congress)

President Trump’s executive orders to temporarily ban Muslims and refugees and crack down on undocumented immigrants hurl America back to the dark days of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, when Congress first passed a law barring a specific immigrant group based on race and national origin.

Like Trump’s Muslim travel ban, the Chinese Exclusion Act scapegoated a specific ethnic group based on false assumptions and public prejudices. During a time of economic depression, politicians and white workingmen falsely blamed Chinese laborers for lowering wages, taking away jobs and draining the economy. As the first group of non-European immigrants to come to the United States, the Chinese were condemned as unassimilable, vile heathens, unfit to ever become American citizens. Physically different, they were easy targets of discriminatory laws and racial hostility.

As early as 1870, the California Legislature passed a law denying entry to Chinese immigrant women unless they could prove they were “of correct habits and good character.” Politicians, fanning the flames of prejudice and blame, pressured Congress to restrict Chinese immigration, culminating in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years and denied Chinese people the right to naturalization.

Trump is using similar tactics to pander to his support base and to justify his anti-immigration policies. Claiming “Islam hates us” and that all Muslims are potential terrorists, he has called for a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the country. Never mind that, since 9/11, nobody in the U.S. has been killed in a terrorist attack by anyone from the seven Muslim countries named in his ban, or that national security experts have said the ban will not make America safer.

Trump—blaming undocumented immigrants for reducing wages and jobs and sapping American resources, and “bad hombres” for drugs and crime—also has ordered increased border enforcement to stop and deport all unauthorized immigrants. Never mind studies showing that the majority of the United States’ 11 million undocumented immigrants are productive taxpayers and that immigrants commit fewer crimes per capita than people born in the U.S.

Trump’s initial ban barring the return of permanent residents and visa holders from seven mostly Muslim countries has been struck down in the courts, as has a subsequent attempt. Twenty-thousand Chinese laborers with re-entry permits did not fare as well in 1888. After visiting their families in China, the Scott Act barred their return.

Trump claims his Muslim ban is temporary. The Chinese Exclusion Act was also supposed to be a temporary measure, enacted for 10 years, but it was renewed for 10 more with the 1892 Geary Act. This act required all Chinese to register for Certificates of Residence or risk imprisonment and deportation—similar to the Muslim registry established after 9/11. By 1904, the Exclusion Act was made permanent, and in subsequent years Congress passed additional laws—the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, the Immigration Act of 1917, the Immigration Act of 1924 and the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934—to exclude immigration from Japan, South Asia and the Philippines and restrict immigration from Southern and Eastern European countries.

If Trump’s temporary ban continues to follow the trajectory of the Chinese Exclusion Act, it could prove as long-lasting and far-reaching. Already, on the coattails of Trump’s reducing the cap on refugees by 50 percent, Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., has introduced a bill that would likewise reduce legal immigration “and give working Americans a fair shot at wealth creation.”

Trump’s inflammatory and divisive rhetoric and actions have led to a climate of racial hatred and religious intolerance, resulting in a surge of hate crimes against Muslims, Arabs, South Asians and Jews. Throughout the country, mosques have been vandalized and burned, Jewish cemeteries desecrated and community centers threatened with bombing, Muslim women and children harassed in the streets and schools, and Muslims and South Asians attacked and killed by men shouting, “ISIS, ISIS,” and “Go back to your own country.” In the 1880s, the demand that “Chinese must go” escalated into murderous mobs storming Chinese settlements—looting, lynching, burning and expelling the residents. One of the worst massacres occurred in Rock Springs, Wyo., when a mob of armed white men opened fire on defenseless Chinese miners, killing 28, wounding 15 and burning all 79 Chinese homes.

Resistance to Exclusion

Refusing to be driven away, Chinese fought back through diplomatic channels, public protest and litigation. The Chinese Consulate repeatedly protested anti-Chinese laws and violence, reminding the U.S. government of its treaty obligations to protect the rights and lives of Chinese subjects. Community leaders and organizations such as the Chinese Six Companies wrote newspaper articles defending the Chinese and sent petitions to the president and Congress protesting Chinese exclusion. They also hired white attorneys to challenge anti-Chinese laws and immigration officials’ exclusion decisions. In the landmark 1898 case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of an American-born Chinese man who had been refused re-entry into the country, stating that all people born in the United States are citizens and cannot be stripped of their rights, regardless of race or the immigration status of their parents. But when 100,000 Chinese, in a courageous act of civil disobedience, refused to obey the 1892 order to register for certificates of residence, they lost that court battle and were forced to comply.

“A Statue for Our Harbor,” The Wasp, 1881. (The Ohio State University Cartoon Research Library)

On May 16, 1905, Shanghai merchants joined the fight to pressure the United States into modifying its stringent anti-Chinese immigration policies by calling for a boycott of American imports. Within a short time, the boycott spread throughout China and was sustained for 10 months. Although the Chinese government caved in to political pressure from President Theodore Roosevelt and halted the boycott, it secured the president’s promise that the immigration service would treat Chinese immigrants less harshly.

Chinese people, desperate to escape political and economic instability in China, circumvented the unjust exclusion laws however they could, becoming the United States’ first “illegal immigrants.” Some slipped into the country from Mexico or Canada. Others entered by falsely claiming exempt status as merchants or U.S. citizens, or as family members—“paper sons” and “paper daughters”—of these exempt classes. In response, the immigration service doubled down on patrolling the borders, detaining Chinese applicants for extreme vetting and conducting raids and mass deportations—exactly what Trump’s administration is doing today.

Border Enforcement

Initially, the greatest trouble spot for Chinese illegal immigration was at the Mexican border, so that was where the immigration service concentrated its resources. As many as 80 immigration officers were assigned to patrol the border, apprehend those caught crossing and deport them. The officers systematically searched all railroad cars traveling from Mexico to the U.S. They also conducted undercover investigations of Chinese smuggling and sweeping raids in the Chinese community.

One could say that enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act at the border was a trial run for control of Mexican immigration in later years. Today, the Mexican border has become a militarized zone designed to stop undocumented immigration from Mexico at any cost. The U.S. spends $4 billion every year on the latest technology, building walls and paying as many as 20,000 agents to patrol the border around the clock. Still, that is not enough for Trump, who has called for building a “Great Wall” (costing $20 billion) and the hiring of 5,000 more border patrol officers, despite unauthorized entries at the border being at its lowest level.

Detention and Extreme Vetting

The Chinese Exclusion Act gave birth to the bureaucratic machinery that enforces U.S. immigration laws, including immigration inspectors and detention facilities. The immigration station at Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay was built in 1910 to better enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chinese immigrants underwent longer examinations, interrogations and detentions than any other ethnic group. They were subjected to invasive examinations of their blood and waste products to detect parasitic and contagious diseases. Applicants were asked minute details about family history, relationships, living arrangements and everyday life in the village. The most innocent discrepancy in a response could mean exclusion and deportation. Often, these interrogations went on for days. Those with legitimate claims sometimes failed the exam.

Despite the State Department’s position that the vetting process for refugees coming to the U.S. is highly rigorous, taking as long as two years, Trump is demanding what he calls “extreme vetting,” subjecting Muslim applicants to even more challenges in overcoming religious-racial assumptions about their fitness for inclusion.Given the arduous process and long delays, Chinese were detained at Angel Island for weeks and months at a time (up to two years for those appealing their cases). They were locked up in quarters that government inspectors declared overcrowded, unsanitary and unsafe, fed shoddy food and forbidden visitors until their cases had been settled. To vent their anger and frustrations, many men carved poems into the barrack walls. Still visible today, the poems bear witness to the indignity and trauma they suffered while imprisoned on Angel Island. (See poems and oral histories collected in “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940” and the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation website.)

Since 9/11, as many as 400,000 immigrants and refugees—mainly people of color, including Chinese—have been detained annually in a patchwork of federal detention centers, state and county jails, and privately run prisons all over the country, with incarceration periods generally ranging from 37 days to 10 months (the longest so far being nine years), and under far worse conditions than those at Angel Island. Detainees have complained about inhumane conditions: overcrowded quarters, inadequate medical care, poor food, lack of access to legal counsel, and sexual and physical abuse. Since 2003, 165 people have died while in detention, more than half because of poor medical care.

Yet Trump has ordered an expansion in detention facilities to accommodate all the unauthorized immigrants he plans to catch at the border, as well as those already living in the country. Under his administration, everyone caught crossing the border without authorization will be detained until they are removed from the country. He condones the continued use of private contractors, even though their facilities are poorly run because of lack of federal oversight and staff trained in immigration law enforcement.

Raids and Mass Deportation

Under Trump’s order for expedited removals, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has been given additional resources and wide latitude for raids and the deportation of anyone it finds in the country without documentation, not just those convicted of serious crimes. The groups at risk of deportation now include anyone charged with a criminal offense, such as crossing the border, abusing any public benefit program or posing a risk to public safety or national security. In short, the president’s goal is to make good on his campaign promise to deport all 11 million undocumented immigrants.

Here, too, history is repeating itself. The Chinese Exclusion Act gave peace officers and U.S. marshals the authority to arrest and deport any Chinese person suspected of being in the country “illegally.” That included people who had not maintained their exempt status (merchants, teachers, students, tourists) under which they were admitted. A reign of terror descended upon the Chinese community in the early 1900s, when immigration officers began aggressively raiding places of business and private residences. Residents complained about their brutal tactics—smashing down doors, unlawful searching baggage and trunks, insulting and physically abusing Chinese under their control, fabricating statements and writing misleading reports in the process. Thousands of Chinese immigrants were deported as a result.

In the 1950s, federal agents raided Chinatown businesses, organizations and even cemeteries looking for evidence to deport immigrants who were pro-Communist China. Chinese community leaders brokered a controversial agreement with the government, thereby reducing the specific number of indictments and deportations but increasing the potential for accusations and interrogations. All Chinese, legal or not, suffered fear and trauma from the omnipresent threats.

“What Shall We Do With Our Boys?” by George Frederick Keller, The Wasp, 1882. Chinese laborers were blamed for the unemployment of American boys.

During the Great Depression, U.S. government officials and local police rounded up Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in deportation raids that led to more than 1 million people being repatriated to Mexico without the legal right to ever return. More than 2,000 Filipinos were also sent back to the Philippines as a result of the Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935. Today’s drastic and sweeping actions taken by the federal government in the name of national security are again wreaking havoc in immigrant communities—threatening constitutional protections, destabilizing families, undermining worker rights and creating an atmosphere of fear, chaos and trauma.

The Impact and Legacy of Chinese Exclusion

The same race prejudice that produced the Chinese Exclusion Act led to the internment of Japanese-Americans, native as well as foreign-born, during World War II. With China a wartime ally, however, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act as a goodwill gesture. And President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose Executive Order 9066 was responsible for Japanese internment, called Chinese exclusion a “historic mistake.” Finally, Chinese aliens were able to become naturalized citizens. Yet only 105 Chinese were permitted to immigrate to the U.S. each year. Not until Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was racial and national discrimination at last erased from our immigration laws and Chinese immigration put on par with that of other nations.

By then, 60 years of Chinese exclusion had devastated the Chinese-American community. The Chinese population in America was drastically reduced. Chinese laborers, unable to send for their wives from China, were condemned to a bachelor’s existence. Equally damaging were the psychological wounds inflicted upon Chinese immigrants and their children—the implication that they were racial inferiors, social pariahs and perpetual foreigners unfit to become Americans. Some, denied the American dream, returned to China. Those who stayed were forced to live in Chinatown ghettos in the shadows of society, in constant fear of detection and deportation by immigration authorities until the day they died.

Even today, hundreds of thousands of Chinese-Americans born to immigrants who came to the U.S. under false identities carry psychological burdens from the effects of enforced deception, threat of deportation, families broken by exclusion. Now, under the Trump regime, millions of other undocumented families fear family separation, forced removal from homes and the destruction of lives built over decades.

For a long time, Chinese-American organizations pressed Congress to publicly acknowledge the error of the Chinese Exclusion Act. In 2012, a mere five years ago, they succeeded, when both houses of Congress passed resolutions to express regret for the act, which “resulted in the persecution and political alienation of persons of Chinese descent, unfairly limited their civil rights, legitimized racial discrimination, and induced trauma that persists with the Chinese community today.” The resolutions (Senate Res. 201 and House Res. 683) also reaffirm Congress’ commitment to preserve the civil rights and constitutional protections for all people, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

That commitment must hold firm against codifying Trump’s unjust, racist and Islamophobic executive orders into law. Indeed, Congress must actively oppose the president’s ill-conceived immigration agenda, which stands to cost taxpayers $600 billion. As a people who know too well the tragic consequences of exclusion, Chinese-Americans stand in defense and in solidarity with Muslims, immigrants and refugees being targeted today.

Because the country has benefited greatly from the contributions of immigrants, it is the responsibility of all Americans to help fulfill the promise of our Constitution for a more perfect union.

Judy Yung is professor emerita of American Studies at UC Santa Cruz, the author of “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island,” and a volunteer with NoMoreExclusion.org.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.